Mormon History

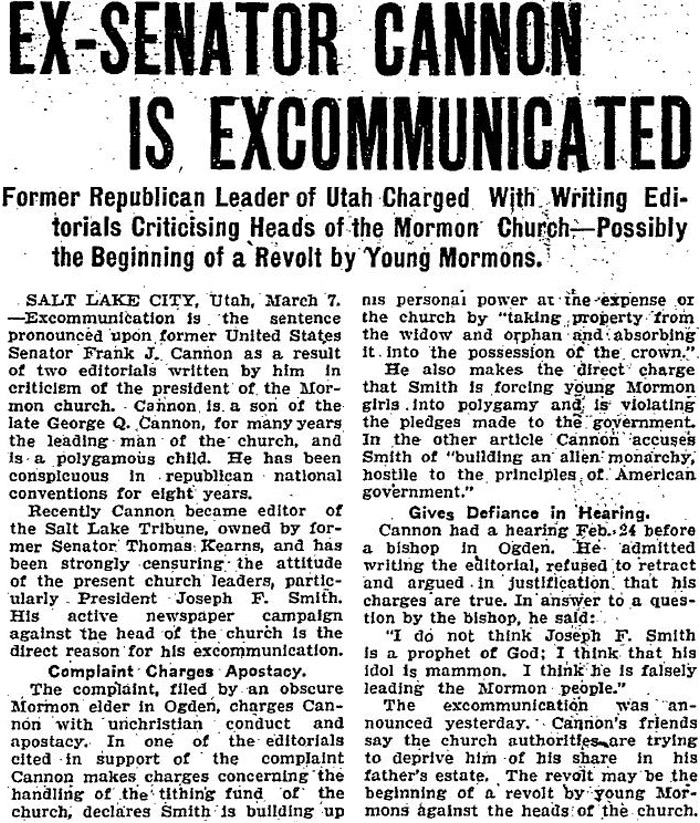

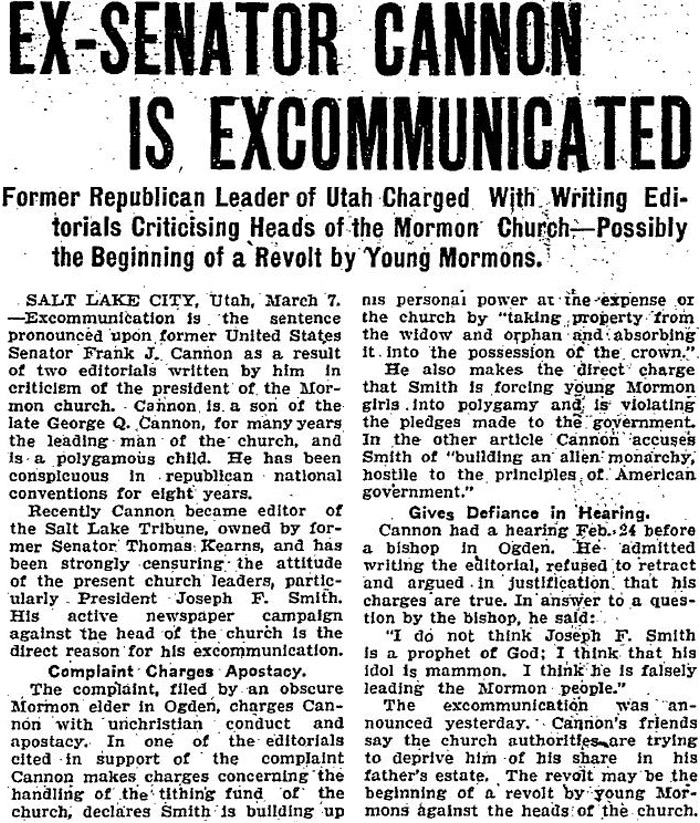

Former Senator is Excommunicated - 1905

The Quincy Daily Journal - March 7, 1905, page 1

Frank J. Cannon was a thorn in the Mormon Church 100 years ago

Posted on February 23, 2011 by Doug Gibson

Standard Examiner

Frank J. Cannon, son of the LDS leader, George Q. Cannon, Mormonism’s most famous apostate, led the Salt Lake Tribune’s editorial assault on the LDS Church, Sen. Reed Smoot, and particularly President Joseph F. Smith from the years 1904 to 1907.

Historians Michael Harold Paulos and Kenneth L. Cannon II have done a great job preserving Cannon’s contributions. Even those Latter-day Saints who agree with his most fervent critics should acknowledge FJC’s many contributions to LDS history.

He was more than a writer and editor. FJC was a paradox: An educated, accomplished advocate and diplomat, editor at the Ogden Standard, missionary to the Sandwich Islands, LDS Church authorities utilized his many talents to negotiate statehood for Utah. Later, FJC served as the Utah territory’s U.S. senator.

However, FJC also was a man of many personal weaknesses. His vices included drinking and patronizing brothels. These weaknesses in following LDS Church laws were tolerated, or at least partially forgiven, while his dad, George Q. Cannon lived. But after his father died, FJC saw his influence within the church’s hierarchy wane quickly. The result was an antipathy toward his longtime faith’s leaders that would last the rest of his life. In fact, his anger, while always eloquent, would sometimes be so over the top as to backfire and generate sympathy for his targets.

FJC’s editorials during the Smoot hearings, between 1904 and 1907, are masterful polemics, designed to amuse, humiliate, sneer, attack, moralize and infuriate LDS Church supporters. One who was very often infuriated was then-LDS Prophet Joseph F. Smith, who not surprisingly, seethed at the savage pen of FJC, which accused the LDS leader of being a traitor to the United States, a traitor to the original LDS Church, a dictator in Utah, and an unrepentant polygamist. In public, Smith mostly avoided mentioning FJC. In private, he called him many names, including a “son of Perdition,” which is an LDS term for those consigned to hell.

Besides attacking Senator Smoot, FJC also enjoyed taunting Deseret News editor — and LDS apostle — Charles W. Penrose, as a toady for the LDS Church. An example: “Probably the only person in Utah who doesn’t know the Mormon Church is in politics up to its very eyebrows, is Apostle [Charles W.] Penrose, of the Deseret News. The Church has to keep things secret from Penrose. He is a new apostle, and, like President Smith blats out everything he knows. … Penrose ought to wash windows. He takes to soapsuds”

But FJC saved his harshest criticism for the prophet. He mocked the LDS leader’s claim on Capitol Hill that he had never received revelation and later called him “God’s Appointed Liar” after Smith justified his testimony to many perplexed Latter-day Saints as a way to avoid being trapped by hostile questioners. For example, FJC editorialized: “Gentiles and Mormons, you are front to front with the proposition. Either you must accept Joseph F. Smith as the prophet of God, ordained to speak falsehoods or truth at his pleasure, ratified by God as a liar or a truth teller to meet the prophet’s needs; or, you must consider him a false, deceiving, lying, hypocritical old man, who clings to his power with selfish hands, and who fain would live out the balance of his life with his five wives …”

Why FJC hated Joseph F. Smith so fiercely is still debated by historians. FJC’s father, George Q. Cannon, whom Frank loved, had a long in-depth business relationship with the prophet. Historians opine that JC may have blamed President Smith for cutting him off from the church’s hierarchy after his dad’s death.

I favor the theory that FJC blamed President Smith for the death of his brother, apostle Abraham H. Cannon, who died in the mid-1890s shortly after marrying another wife, years after polygamy was abolished. In FJC’s opinion, stress from the secret marriage harmed his brother’s health.

Cannon was excommunicated by the LDS Church long before the Smoot hearings concluded. His barbed editorials continued until Smoot was eventually cleared by the U.S. Senate. Soon afterwards, Cannon left Salt Lake City and worked at the Post and the Rocky Mountain News.

His sabbatical as an anti-Mormon crusader would resume soon, and “Round 2″ would continue for a generation, both as author of a best-selling “expose” on Mormonism and his longstanding gig at chautauquas, a series of lectures, dances, debates, plays and music offerings then popular across the country that Paulos and Cannon describe as the forefront to modern adult education. At one chautauqua event where Cannon lectured, he was confronted by a group of outraged LDS priesthood holders. But we’ll save that for next week’s Standard Works column.

(For an excellent look at Cannon’s editorials, Paulos and Cannon II prepared a small, privately published book, “Selected Frank J. Cannon Salt Lake Tribune Editorials during the Reed Smoot Hearings and Snippets from Frank J. Cannon’s Campaign Against Mormonism during the 1910s.” The book, which includes an introduction by Will Bagley, was presented at last year’s Mormon History Association Association. It is not sold, but is available at some libraries.

Born in Salt Lake City, he was the eldest child of Sarah Jenne Cannon and George Q. Cannon. His father was an Apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints First Presidency. After attending the school in Salt Lake City, he studied at University of Deseret, graduating at the age of 19. He would marry Martha Brown of Ogden in 1878.[2] and later was a member of its

In 1891 he helped to organize the Utah Republican Party.[3] After a failed bid to become Delegate from the Utah Territory, he succeeded and served from March 4, 1895 to January 4, 1896. Cannon was chosen in the latter year to serve as Senator by the Utah Legislature in spite of LDS church leadership favoring his father for the job. He served in the United States Senate, initially, as a member of the Republican Party; however, he later became a member of the Silver Republican Party[4] founded by his successor (and future employer at the Salt Lake Tribune) Thomas J. Kearns.[5] Cannon affiliated with the Democratic Party in 1900 and served as its state chairman 1902-4.[6]

After failing to be re-elected to the U.S. Senate by the Utah legislature, in part due to opposition by the Mormon hierarchy,[citation needed] Cannon then worked as the editor of several newspapers, including the Salt Lake Tribune,[7] the Ogden Herald (Ogden, Utah) and established the Ogden Standard.[citation needed] Between 1904 and 1911, Cannon consistently supported the anti-Mormon American Party in newspaper editorials.

Cannon later rejected Mormonism and wrote a book, with Harvey J. O'Higgins, called Under the Prophet in Utah exposing the rigidly hierarchical nature of the Mormon organization. The book denounced what the authors described as the "church" leadership's "absolutism" and "interference" in politics: "[Mormons] live under an absolutism. They have no more right of judgment than a dead body. Yet the diffusion of authority is so clever that nearly every man seems to share in its operation... and feels himself in some degree a master without observing that he is also a slave".[8] The book details the negotiations Cannon participated in on Utah's behalf leading to statehood in exchange for official rejection of polygamy and LDS leadership's domination of civil politics during the 1890s, and the subsequent back-sliding he observed in the years following statehood.

During the last two decades of his life, he lectured against Mormonism and in support of "free silver" policies (as opposed to the Gold Standard). He died, at the age of 74, in Denver, in 1933.[9]