9/11/1857 MORMON MOUNTAIN MEADOWS MASSACRE COVER-UP

History of Indian Depredations in Utah (no mention of the Mormon Mountain Meadows Massacre) - 1919

John Taylor's sermon on his treason and hatred of the United States of America - 8/231857

Mountain Meadows Mormon Massacre Smoking Gun Sermon - 9/13/1857

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

The tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857

Brigham Young Preaching Murder in the 1850s

Philip Klingon Smith Confession

More Information on the Mormon Mountain Meadows Massacre

Interior secretary designates Mountain Meadows Massacre site a historic landmark

Written by: Dan Metcalf Jr.

June 30, 2011

SALT

LAKE CITY (ABC 4 News) - U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar

announced the designation of the Mountain Meadows Massacre site in

Washington County as a national historic landmark.

The site is the location where approximately 120 people were killed by

a mob comprised of the Iron County district of the Utah Territorial

Militia and some local Indians.

The massacre took place on September 11, 1857 with the slaughter of an

immigrant party from Arkansas during a time of hysteria in Utah among

members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who feared

the U.S. government might invade to take control of the territory.

Several children were spared by the mob.

A memorial stands at the site that was constructed and dedicated in

1999 with financing and cooperation of the LDS Church and the Mountain

Meadows Association.

The controversial event has been a subject of debate by historians and

families of survivors for several decades.

The Mountain Meadows site is one 14 historic U.S. designations announced

by Salazar on Thursday.

“Each of these landmarks represents a chapter in the story of America,

from archeological sites dating back more than two millennia to

historic train depots, homes of famous artists, and buildings designed

by some of our greatest architects,” said Secretary Salazar. “By

designating these sites as national landmarks, we help meet the goals

of President Obama’s America’s Great Outdoors Initiative to establish a

conservation ethic for the 21st century and reconnect people,

especially young people, to our nation’s historic, cultural, and

natural heritage.”

----Information from: U.S. Dept. of the Interior.

Mountain Meadows Massacre descendants meet

BY GERALD CARROLL

Tulare Advance-Register

September 11, 2010

Sept. 11 is a special day for more reasons than the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, say a group of visitors convening this weekend in Tulare On Sept. 11, 1857, an incident known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre took place in southwest Utah when 120 members of an Arkansas-based wagon train bound for Tulare were killed by a violent faction of the Mormon church, experts say.

"You might call it the original 9/11," said former College of the Sequoias history professor Newell Bringhurst, who wrote a biography of Mormon patriarch Brigham Young published in the 1980s. "It was a perfect storm in terms of why such a massacre could happen."

The incident remains buried in political turmoil, even to this day, and was a media sensation for more than 20 years after it happened. However, only in the 21st century is the full accounting of the massacre gaining public attention, foundation members say.

Movie released in 2006

A 2006 movie, "September Dawn," starring Jon Voight, is based on the massacre.

"I was at the premiere," said 83-year-old Dr. Burr "Old Doc" Fancher, an Albany, Ore., resident with Arkansas roots whose life's work in recent years has been piecing together the story and tracking down ancestors of 17 young children who were spared that day.

"Voight encouraged us," said Fancher, the main speaker in today's 5 p.m. dinner and historical presentation. Organizers reported 56 signups as of Friday night, many from other states and many who have never been to Tulare.

Fancher is a direct descendant of Capt. Alexander Fancher, who led the wagon train and who was killed in the attack.

"I lost 30 ancestors that day," Fancher said.

Media attention was widespread in the massacre's aftermath.

"That incident drew just as much media attention for that time in history as the 9/11 attacks did in 2001," said Ron Wright, another descendant of the victims.

Massacre chronology

Militant Mormons in the southwest part of Utah were said to have dressed as Indians and attacked the wagon train on Sept. 7, 1857. However, defenders of the wagon train fought back, and held off the assault until Sept. 11. At that point, the attackers removed their Indian disguises and posed as "white" liberators, only to kill the wagon-train defenders after luring them away from their belongings.

Decades of high-profile litigation followed, with survivors' families accusing the Mormon church of as coverup, and eventually one man was convicted of participating in the massacre and executed by firing squad in 1877.

"The wagon train was crossing Utah at the worst possible time," said Bringhurst, a non-practicing Mormon and local expert in Mormon history. "A U.S. army was heading toward Utah. Mormons considered outsiders enemies."

Fancher said the foundation harbors no ill will toward Mormons and that the primary mission of the group is to "memorialize" the slain wagon-train members and the 17 children — deemed "too young" to bear witness to the tragedy — who were spared.

Fancher said that 15 of the 17 surviving children's graves have been located in various states, and that the foundation is closing in on the other two.

"All the confirmed graves of those surviving children will be marked with a $500 historical memorial," Fancher said.

Tulare's historical museum is one of seven locations around the country where a repository of documentation about the Mountain Meadows Massacre can be found.

"Tulare would have made a great home for those people." Fancher said. "They just didn't make it."

Innocent

Blood

Essential Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre

Edited by David L. Bigler, Will Bagley

Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier Series

Volume 12

Original sources documenting a frontier atrocity and its cover-up.

The slaughter of a wagon train of some 120 people in southern Utah on

September 11, 1857, has long been the subject of controversy and

debate. Innocent Blood gathers key primary sources describing the

tangled story of the Mountain Meadows massacre. This wide array of

contrasting perspectives, many never before published, provide a

powerful and intimate picture of this "dastardly outrage" and its

cover-up.

The documents David L. Bigler and Will Bagley have collected offer a

clearer understanding of the victims, the perpetrators, and the

reasons

a frontier American theocracy sought to justify or conceal the

participants' guilt. These narratives make clear that, despite limited

Southern Paiute involvement, white men planned the killing and their

church's highest leaders encouraged Mormon settlers to undertake the

deed.

This compelling documentary record presents the primary evidence that

tells the story from its contradictory perspectives. The sources let

readers evaluate and track the evolution of such myths as the Paiutes'

guilt, the emigrants' provocation of their murderers, Brigham Young's

ignorance of what happened, and John D. Lee's sole culpability.

Clearly

revealed is the part Utah authorities took in blocking the

investigation until it became expedient to sacrifice Lee.

Together, these narratives show how the massacre's story has been

continually distorted and then revealed over 150 years—and how the

obfuscation and cover-up continue. Innocent Blood conveys the

encompassing impact the atrocity had on people's lives, then and for

generations after. It is a valuable sourcebook sure to prove

indispensable to future research.

About the Authors

David L. Bigler, former director of the Utah Board of State History,

is

an independent historian whose award-winning books on Utah,

California,

and western American history include Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon

Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896. Will Bagley, an independent

historian of the West, is author of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham

Young and the Mountain Meadows Massacre and editor of Pioneer Camp of

the Saints: The Mormon Trail Journal of Thomas Bullock, 1846–1847.

"A Sight Which Can Never Be

Forgotten"

Archaeology Magazine

September 16, 2003

The Mountain Meadows Massacre

U.S. Army Brevet Major James H. Carleton surveyed and investigated the

site in 1859, and reported to Congress that the Mormons were "painted

and disguised as Indians." According to Carleton, Lee led the

disguised

group of Mormons and local Paiute Indians to the emigrants' camp and

attacked. As the emigrants fought back, the attackers utilized a new

strategy. They withdrew, then the Mormons removed their disguises and

returned as a group of white men, telling the emigrants they would

protect them from the attackers. The Mormons gained the trust of the

emigrants, convincing them the Indians would not hurt them if they

gave

up their arms. Lee's testimony supports Carleton's report, but Lee

offers more gruesome details. He explains that "the troops were to

shoot down the men; the Indians were to kill all of the women and

larger children." In both Carleton's and Lee's accounts the Paiutes

and

Mormons share the responsibility of the murders, but the Paiutes have

long denied involvement.

Since its beginning, the Church of Latter-day Saints (LDS) was at odds

with the federal government, its members persecuted for their

unorthodox beliefs. Mormonism began in the early nineteenth century

with the prophecy of Joseph Smith who wrote the Book of Mormon derived

from golden plates he found near a family farm in 1827. From New York,

Smith and his followers were continually forced west, their radical

theology shunned by each town in which they settled. In 1844, Joseph

Smith was killed by an anti-Mormon mob in Illinois, and Brigham Young

became the new Prophet. The Mormons finally settled in the Utah

territory where they enjoyed autonomous political and religious power.

Young was not only in charge of the church, but also of the state when

President Millard Fillmore named him territorial governor of Utah in

1850. In the fragile pre-Civil War era, Young openly flaunted

secessionist tendencies. In its attempt to develop its own theocratic

government, the church often clashed with the federal government,

creating a mutual feeling of distrust.

Maj. Carleton, in his report to Congress, describes the scene at

Mountain Meadows: women's hair caught in sage bushes, children's bones

found in their mothers' arms, and wolves picking at the bones. It was,

he wrote, "a sight which can never be forgotten." Carleton buried the

remains and piled rocks into a monument topped by a wooden cross on

which he inscribed "Vengeance is mine: I will repay, saith the Lord."

Soon after, Brigham Young and his men tore down the monument. Over the

next century, it would be rebuilt and destroyed several times,

standing

in the nearly inaccessible and otherwise unmarked massacre site. As

time passed, the descendants of the victims demanded a permanent

monument to honor their ancestors, and Brigham Young's descendants

wanted to clear his name. In an attempt to keep both parties happy,

the

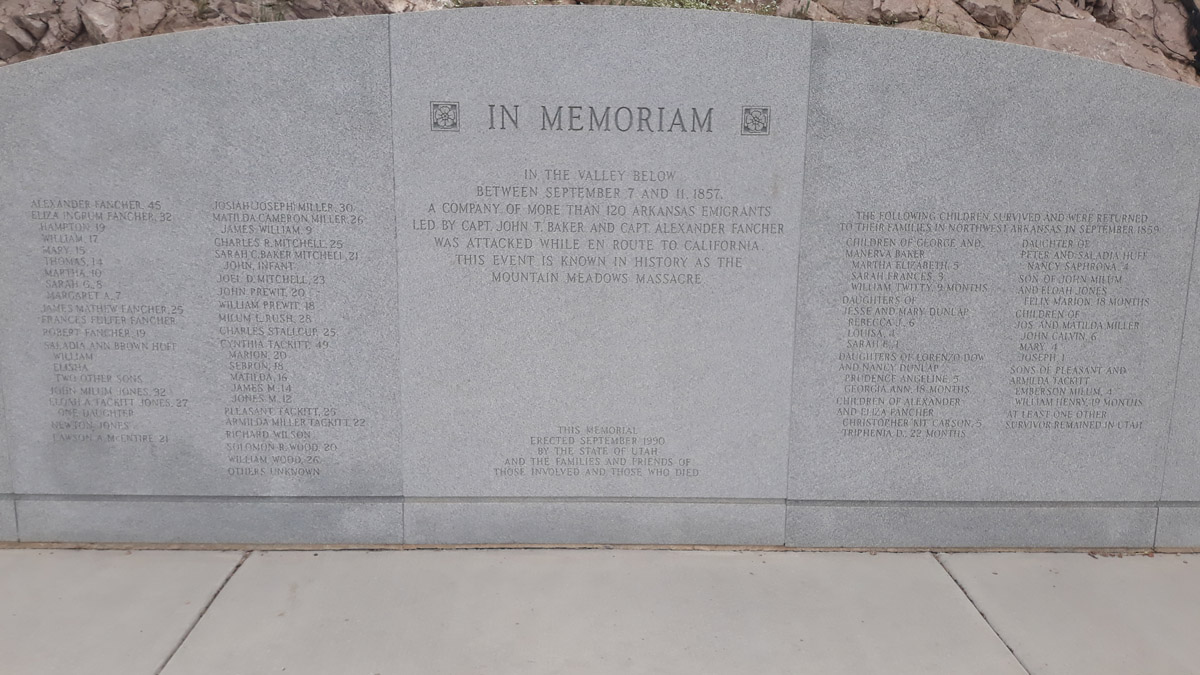

state finally built a permanent monument in 1990, an ambiguous

inscription engraved in a granite wall: "In Memoriam: In the valley

below, between September 7 and 11, 1857, a company of more than 120

Arkansas emigrants led by Capt. John T. Baker and Capt. Alexander

Fancher was attacked while en route to California. This event is known

in history as the Mountain Meadows Massacre."

Once again the monument fell to disrepair, this time because of

weather

and poor construction. The descendants made it clear to the government

that the monument needed to be repaired or replaced. The LDS Church

hired Shane Baker, an archaeologist from Brigham Young University, to

survey the land before a new monument could be built. Baker reportedly

found nothing relating to the massacre, clearing the way for the

construction of the new monument. On August 3, 1999, a backhoe began

digging the foundation. To everyone's surprise, it scooped up the

bones

of 28 massacre victims, and with it unearthed a new controversy (see

"Mountain Meadows Massacre," November 30, 1999).

Utah state law required that the bones be studied, a job that went to

forensic anthropologist Shannon Novak from the University of Utah.

Novak and her colleagues found entrance and exit holes in the skulls

of

men that could only have come from gunshots fired at close range,

while

most women and children found died of blunt force. In her analysis of

more than 2,600 bone fragments, Novak found no evidence of knives used

to scalp, behead, or cut the throats, as well as no evidence of trauma

from arrows. Although the study cannot determine what weapons Paiutes

might have used in the massacre (if they were involved), it brings up

the possibility that white men murdered all of the victims,

contradicting John D. Lee's testimony accusing Native Americans of

slaughtering the women and children. To Shannon Novak, the bones could

provide information that incomplete or biased histories could not.

"Prior to this analysis, what was known about the massacre was often

based on second-hand information, polemical newspaper accounts, and

the

testimony of known killers," said Novak. "Furthermore, what had come

to

be merely an abstract historical event, the 'tragedy at Mountain

Meadows,' now became a mass murder of specific men, women, and

children

with proper names and histories." The analysis of the remains

questioned the accuracy of the historical accounts and stirred up many

emotions. After five weeks, Novak's analysis was cut short by an order

from the governor of Utah, Mike Leavitt, that the bones be re-interred

in time for the September anniversary.

Gene Sessions, historian and president of the Mountain Meadows

Association (an organization for descendants of the victims), says

that

the descendants, anxious to leave this issue buried in the ground,

appealed to the governor. Leavitt, whose grandfather participated in

the massacre, circumvented the law and ordered that the bones be

re-interred before the minimum required study was finished because he

"did not feel that it was appropriate for the bones to be dissected

and

studied in a manner that would prolong the discomfort" (Salt Lake

Tribune, March 2000). Despite efforts of the Mormon Church to work

with

descendants in building the monument, Baker's fruitless survey and the

early re-interment of remains sparked allegations that the LDS Church

intentionally kept information from the public to coverup their

involvement in the massacre. Sessions insists that "there was never

any

attempt to hurry the bones back into the ground to 'hide' anything,"

and the descendants strongly opposed any further disturbance of the

bones. He argues that "the bones reveal nothing that historians have

not known since 1859 when Major Carleton reported that 'nearly every

skull I saw had been shot through with pistol or rifle bullets.' As a

scholar, I naturally believe that a further study of the bones would

certainly reveal much detail, but I do not believe that they would

reveal anything I do not already know from the historical record abut

how the emigrants were killed and who did it."

Shannon Novak, who has interviewed victims' descendants as part of a

two-year oral history project, says she has heard a wide range of

opinions on the story of the massacre and the treatment of the site.

Some want the bones left untouched, without reminders of the event.

Some would like to see the bones returned to Arkansas for a mass

burial. Others want to see the bones examined with DNA testing to

identify and properly bury their ancestors, allowing a sense of

closure. While some have reconciled with the LDS Church, Novak claims

that "many or most would like an apology from the church before they

would be prepared to put the event behind them." For now, the bones

remain behind a plaque at the memorial.

The discovery of the bones complicated an already controversial issue.

There is no consensus by descendants, researchers, and the LDS

church on what should happen to the remains. The tragedy stirs up deep

emotions in the descendants of both the victims and the attackers, and

causes one to question whether or not the remains provide insight into

the Mountain Meadows Massacre that the historical record does not. In

her forthcoming book, however, Shannon Novak addresses her

osteological

analysis in relation to historical records and recent controversies.

Novak found that "The material evidence from the grave appears to have

offered some groups and individuals their first opportunity to express

their views of the massacre, views that often were in conflict with

the

traditional accounts touted in state history textbooks and on local

monuments."

A bizarre twist to the Mountain Meadows story came in January 2002, when a volunteer found an inscribed lead sheet while cleaning out John D. Lee's fort just across the Utah border in Arizona. The writing, purportedly by Lee, indicated Brigham Young's role in ordering the massacre. Examiners agree that the lead comes from a time and place historically correct to be the document, and contains oxidation on the inscription itself. After investigating the metal and oxidation using isotopic measurements, Thomas Brunty of Arizona State University told the Salt Lake Tribune on March 7, 2003 that "It would take a hoaxer a lot of resourcefulness to have found the right lead from the right place."

A Shameful Chapter in Mormon History

Cecilia Rasmussen

Los Angeles Times

June 29, 2003

As evidence emerged over time -- most recently in an excavation in 1999 -- the massacre was shown to have been the handiwork of about 50 Mormons, many of them disguised as Indians. They were commanded by John Doyle Lee, a prominent and wealthy Mormon and a friend of Brigham Young, who was [Joseph Smith]'s heir and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

President Buchanan declared Utah in open rebellion and sent troops to replace Young with a non-Mormon territorial governor. Young responded by placing Utah under martial law and preparing to go to war.

Despite the vows of secrecy, word of what had happened spread through the tightly knit Mormon communities. Many Mormons, shocked by what they heard and saw -- such as fellow Mormons wearing the finery of the dead -- packed up and left.

The Mountain Meadows Massacre took place in southern Utah nearly 150 years ago, but it touched Southern California's history too, leading to the demise of a fledgling Mormon community in San Bernardino.

Early on a Monday morning in September 1857, about 140 men, women and children on a California-bound wagon train were slaughtered under a flag of truce by Mormons who apparently considered the act a long-delayed vengeance, or "blood atonement," for persecution of their faith.

In the 1830s and '40s, Mormons were often tarred and feathered or even killed, and their homes and businesses were burned. Their founder, Joseph Smith, was murdered in 1844 in Illinois, and Mormons retreated into the western wilderness.

When the 1857 massacre occurred at a popular resting place for wagon trains in a valley on the emigrant trail, the Mormon Church blamed Paiute Indians.

It was not only the number of dead that horrified a westward- moving nation; it was the gruesome butchery. Army troops visiting the site almost two years later reported finding skulls, scraps of clothing and clumps of hair still strewn around.

As evidence emerged over time -- most recently in an excavation in 1999 -- the massacre was shown to have been the handiwork of about 50 Mormons, many of them disguised as Indians. They were commanded by John Doyle Lee, a prominent and wealthy Mormon and a friend of Brigham Young, who was Joseph Smith's heir and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Lee, considered by many to have been a scapegoat for Young, was convicted for his role in the murders and executed by firing squad 20 years later at the Mountain Meadows Massacre site.

Sally Denton tells the story in horrifying detail in her new book, "American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857." She draws on official reports of the time, including interviews with witnesses, and on the evidence from the 1999 dig.

In 1846, Young led his people from Illinois to the valley of the Great Salt Lake, a place no one else seemed to want. Young figured it was far enough from the boundaries of the United States to proclaim a new Zion, where Mormons could make their own laws and keep multiple wives.

In 1851, Young sent 437 pioneers from Salt Lake City on an arduous 800-mile trek across harsh desert to settle at the base of the Cajon Pass. Within a year, the Mormons had agreed to buy the 40,000-acre Rancho San Bernardino.

Among the pioneers was Biddy Mason, a slave who would become one of California's richest women and founder of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in Los Angeles. She fought her Mormon owner to win her freedom.

The pioneers built a boom town free of liquor and gambling. It served as a major link in the church's supply line between San Pedro's harbor and Salt Lake City, and as a way station for missionaries and converts heading to Salt Lake. The town's population soon swelled to 3,000.

In 1853, San Bernardino broke away from Los Angeles County, becoming a county in its own right. The town was incorporated a year later.

By early 1857, almost a decade after the Mexican-American War had allowed the United States to expand its territory to include Utah, Mormons in Salt Lake were under pressure from the federal government, whose authority they defied.

President Buchanan declared Utah in open rebellion and sent troops to replace Young with a non-Mormon territorial governor. Young responded by placing Utah under martial law and preparing to go to war.

Against this backdrop, about 200 prosperous and optimistic emigrants left Arkansas for California by wagon train. They passed through Cedar City, Utah, and made camp 35 miles beyond, at Mountain Meadows.

Local Mormons, angry over the recent killing of one of their "apostles" near Arkansas and by the approach of Army troops, viewed the wagon train as a hostile force and refused to sell food to the travelers.

On Sept. 7, 1857, the emigrants were basking in the early morning sun when gunfire rained down upon them. Seven men were killed in the first volley. The others quickly moved the wagons into a barricade. But snipers began picking off settlers one by one, wounding 46 others that day. A bullet tore through the earlobe of a 3-year-old girl.

On the third day of the siege, desperate for water and "hoping to appeal to the humanity of their enemies, the emigrants dressed two little girls in 'spotless white' and sent them with a bucket toward the spring," Denton wrote. "Both were shot dead in an instant."

On the fourth day, a Mormon with a white flag approached the weary, hungry and thirsty immigrants. The travelers were being attacked by Indians, he said; Lee was a federal Indian agent who could escort them safely through Indian territory if they would lay down their weapons and hand over their possessions.

The settlers agreed, only to be betrayed. The men were slaughtered first -- shot, stabbed and clubbed. Then the killers fell upon the women and children.

Two teenage sisters who promised to love and obey Lee in exchange for their lives were stripped of their clothes, raped and brutally murdered.

Seventeen children younger than 8 were allowed to live because the killers believed they were too young to tell credible tales. All were placed in Mormon homes. Some remembered their new "relatives" wearing the clothes and jewelry that had belonged to their slain mothers.

Two children, Rebecca Dunlap, 6, and her sister, Louisa, 4, would be among the first witnesses to report having watched the Mormon killers, disguised as Indians, wash off their war paint in a stream. Rebecca later recounted that they were taken to a ranch with a little boy who had been shot in the leg. He was crying. "The men stopped the wagon. One got out ... took the little boy by the feet and knocked his brains out against the wagon wheel."

Before returning home, the killers pledged to stand by one another and promised to maintain that the massacre had been the work of Paiute Indians.

"This was the advice of Brigham Young too," Lee wrote in a tell- all book while awaiting execution. The book, "Mormonism Unveiled or Life & Confession of John D. Lee," was published in 1877 and became a best-seller.

Paiutes had witnessed the siege but denied any role in it.

Despite the vows of secrecy, word of what had happened spread through the tightly knit Mormon communities. Many Mormons, shocked by what they heard and saw -- such as fellow Mormons wearing the finery of the dead -- packed up and left.

By October, word of the massacre began to filter out to California. The Los Angeles Star newspaper quoted witnesses who had seen two piles of nude bodies. One said, "I saw about 20 wolves feasting upon the carcasses of the murdered."

In late October, as anti-Mormon fury spread in California, San Bernardino colonists were recalled to Utah. Two-thirds of the members obeyed.

The rest refused, not wanting to leave the prosperous and comfortable settlement, yet knowing they would be excommunicated for staying. Some would later join a splinter branch of the church that bore no allegiance to Young. It would be another 60 years before Mormons established an official presence in San Bernardino.

In January 1858, word of the massacre reached Arkansas. The victims' families appealed to the government to investigate the crime and find the surviving children. Eventually, 15 of the orphaned children were found and returned to their Arkansas relatives. An investigation showed enough evidence to put Lee and 37 cronies behind bars but, with the Civil War looming, the massacre was almost forgotten.

Finally, in 1875, the federal government prosecuted John Doyle Lee, trying him in Utah. His trial ended in a hung jury, but he was convicted in a second trial and executed in 1877. He was the only participant brought to justice.

The church denied any official involvement in the crime, but church officials seemed at best insensitive to the victims. A memorial erected two years after the massacre was pulled down in 1861, by Brigham Young himself.

Rescue

of the Mountain Meadows Orphans

Wild West Magazine

February 2005

The forgotten legacy of the massacre in Utah Territory in September

1857 includes the 17 children who were spared by the killers and who

provided some compelling accounts of what really happened in that

Western tragedy.

By Will Bagley

In the fall of 1857, a party of emigrants from Arkansas camped in

southern Utah Territory at Mountain Meadows, a lush alpine oasis on the

Spanish Trail where wagon trains rested before crossing the Mojave

Desert. The party was made up of about a dozen large, prosperous

families and their hired hands, driving about 18 wagons and several

hundred cattle to Southern California.Of its 135 to 140 members, almost

100 were women and children.

As the travelers brewed coffee not long after dawn on Monday, September

7, a volley of gunfire suddenly tore into them from nearby ravines and

hilltops, immediately killing or wounding about a quarter of the

able-bodied men. The survivors quickly pulled their scattered wagons

into a corral and leveled their lethal long rifles at their hidden,

painted attackers, stopping a brief frontal assault in its tracks. The

Arkansans quickly built a wagon fort and dug a pit at its center to

protect the women and children. Cut off from water and under continual

gunfire, the emigrants fended off their assailants for five long,

hellish days.

Finally, on Friday, September 11, hope appeared in the form of a white

flag. The emigrants let the emissary, a Mormon from the nearby

settlement of Cedar City, into their fort, and then the local Indian

agent, John D. Lee, entered the camp. Lee told them the Indians had

gone, and if the Arkansans would lay down their arms, he and his men

would escort them to safety. The desperate emigrants, Deputy U.S.

Marshal William Rogers reported two years later, trusted Lee's honor

and agreed to his unusual terms. They separated into three groups—the

wounded and youngest children, who led the way in two wagons; the women

and older children, who walked behind; and then the men, each escorted

by an armed member of the Nauvoo Legion, the local militia. The

surviving men cheered their rescuers when they fell in with their

escort.

Lee led his charges three-quarters of a mile from the campground to a

southern branch of the California Trail. As the odd parade approached

the rim of the Great Basin, a single shot rang out, followed by an

order: “Do your duty!” The escorts turned and shot down the men,

painted “Indians” jumped out of oak brush and cut down the women and

children, and Lee directed the murder of the wounded. Within five

minutes, the most brutal act of religious terrorism in America history

was over—and it would not be surpassed until a bright September morning

exactly 144 years later, as airplanes filled with passengers were flown

into the Pentagon and New York City's World Trade Center.

So ended the Mountain Meadows Massacre—but the story of this mass

murder and its twisted legacy had only begun. Although “white men did

most of the killing,” as participant Nephi Johnson later admitted, Utah

Indian Superintendent Brigham Young informed Washington that “Capt.

Fancher & Co. fell victims to the Indians' wrath” and blamed the

emigrants for “indiscriminately shooting and poisoning

them”—essentially, Young argued, they got what they deserved. Young

made no effort to investigate the crime or identify the perpetrators.

The murderer—many of whom stripped for battle and donned war paint to

look like Indians—took a blood oath to blame the slaughter on the local

Paiutes (see “Warriors and Chiefs” in this issue), and since they

thought they had killed everyone old enough to tell the emigrants' side

of the story, who could contradict them?

The killers, however, made a mistake: They spared 17 of the children,

believing they would be too young to be credible witnesses. Mormon

doctrine made shedding innocent blood an unforgivable sin, and anyone

under the age of 8 was by definition “innocent blood.” Lee later

claimed he was ordered to spare only children “who were so young they

could not talk.” The Mormons actually killed at least half a dozen

children 8 years old or younger, but in an atrocity notably lacking in

mercy, that belief in not shedding innocent blood saved the lives of 10

girls and seven boys between infancy and age 6.

Yet their youth did not prevent the orphans from leaving behind some of

the most compelling accounts of what actually happened on that black

Friday. “The scenes and incidents of the massacre were so terrible that

they were indelibly stamped on my mind, notwithstanding I was so young

at the time,” Nancy Huff Cates recalled in 1875. The tale of how a

hard-bitten crew of colorful frontiersmen rescued these sad orphans is

one of the great, untold stories of the American West.

The first news of the worst massacre in the history of the Oregon and

California trails appeared in the Los Angeles Star on October 3, 1857.

Several children, it reported, “were picked up on the ground, and were

being conveyed to San Bernardino.” A week later, that newspaper said

the Indians saved 15 “infant children” and sold them to the Mormons at

Cedar City. By the end of the year, word of the murders had reached the

families of the victims in northwest Arkansas, where an angry citizen

asked if the government would send enough men to Utah “to hang all the

scoundrels and thieves at once, and give them the same play they give

our women and children?”

William C. Mitchell's married daughter, Nancy Dunlap, had been with the

so-called Fancher party, as had a married son, Charles, and an

unmarried son, Joel. Mitchell wrote to Senator W.K. Sebastian, chairman

of the Committee on Indian Affairs, expressing his hope that an infant

grandson had survived. He asked Sebastian to investigate: “I must have

satisfaction for the inhuman manner in which they have slain my

children,” he wrote, “together with two brothers-in-law and seventeen

of their children.” Many of the murdered emigrants came from powerful

Arkansas families. In February 1858, the “deeply aggrieved” people of

Carroll County in northwest Arkansas petitioned Congress to appropriate

funds to reclaim and return the children saved from the massacre.

Utah was still in a virtual state of rebellion, however, and not long

after the massacre Mormon guerrillas had burned Army supply trains on

the way to the territory. The government could do nothing much until

June 1858, after Brigham Young's hoped-for alliance with the Indians

collapsed and the “Mormon Revolt” fizzled. Young grudgingly accepted a

blanket pardon for treason and allowed the new governor and federal

judges into the territory. That same month the U.S. Army established

the nation's largest military station at Camp Floyd, 40 miles from Salt

Lake City. Alfred Cumming replaced Young as governor, and Jacob Forney

took over as Indian superintendent. One of their first priorities was

to locate the Mountain Meadows orphans and “use every effort to get

possession” of them, as Washington had first ordered Forney to do back

in March.

Jacob Hamblin, the president of the Mormon Southern Indian Mission, met

with Brigham Young in June and told Young “everything” about the

murders, including that whites were involved. Young told him, “Don't

say anything about it,” and Hamblin loyally continued to blame the

massacre on the Indians. Hamblin told Forney that 15 of the survivors

were living near his ranch with white families. With considerable

effort, Hamblin claimed, the children had been “recovered, bought and

otherwise, from the Indians.” Forney hoped to go south in a month to

recover the children, but he put off the job for almost a year,

although he did tell Hamblin to collect the children.

In early August, Young sent orders to Isaac Haight and William Dame,

religious leaders in southern Utah (and the same men who had given the

direct orders to massacre the Arkansans). He told them to have Hamblin

“gather up those children that were saved from the Indian Masacre

[sic].” Forney also sent orders to Hamblin, “All the children must be

secured, at any cost or sacrifice, whether among whites or Indians.” He

instructed Hamblin to take the children into his family. “You will be

well compensated for all the trouble you and Mrs. Hamblin will have,”

Forney promised.

Hamblin had found 15 of the orphans by December 1858, but he was “satisfied that there were seventeen of them saved from the massacre,” he wrote. He claimed two children had been taken east by the Paiutes, a story apparently concocted to extort government money to pay imaginary ransoms to the Indians. In late January 1859, Forney reported to Washington that he had recovered 17 children (when in fact he had seen none of them), and in March he finally headed south on this errand. Meanwhile, Congress had appropriated $10,000 to locate the survivors of Mountain Meadows and transport them back to Arkansas.

Not long after setting out, Forney learned that $30,000 worth of property and presumably some cash had been distributed among Mormon church officials at Cedar City within a few days of the massacre. He reported that he hoped to recover at least some of the stolen property. He stopped 40 miles south of Salt Lake City to testify before the grand jury that the fearless Judge John Cradlebaugh was holding in Provo. Forney had aligned himself with the federal officials led by Governor Cumming who had aligned themselves—and sometimes lined their pockets—with Brigham Young's interests. Forney and Cumming were timid men, and as heavy drinkers both were easily intimidated. Events soon showed that neither of them had the courage to ensure justice was done for the victims of the massacre, let alone the gumption to stand up to a powerhouse like Brigham Young, “the Lion of the Lord.” Despite detailed, credible evidence that whites and not Indians had committed the massacre, Forney hired Mormons to escort him on his trip to southern Utah.

At Nephi, Forney met up with two remarkable frontiersmen: Colonel William Rogers and Captain James Lynch. Rogers, affectionately known as “Uncle Billy” in both California and Carson Valley, was already a Western legend in 1858 when he moved to Salt Lake City, opened the California House (a hotel “fitted up in superior style”) and quickly won a legion of friends. Two years later, British explorer Richard Burton found Colonel Rogers running the Pony Express station at Ruby Valley, trading furs and managing a government Indian farm for the Western Shoshones. Rogers was already a veteran of many “adventures among the whites and reds,” Burton said, and had “many a hairbreadth escape to relate.” But nothing he did in his long, colorful career was as dangerous as his mission to Mountain Meadows.

Uncle Billy joined Forney at Nephi as an assistant. At the same time, Captain Lynch was leading a party of between 25 and 40 men south from Camp Floyd, where he had worked for the commissary department, to the area that would become Arizona (possibly to prospect there), when he too met Forney at Nephi.

Born in Ireland, Lynch had been orphaned not long after his parents immigrated to Brooklyn, and he had drifted to New Orleans, where he enlisted in the frontier army. Lynch had served under Zachary Taylor and Robert E. Lee in the Mexican War and was cited three times for bravery. (Lynch's captain title, however, was honorary, not military.) After his discharge, he joined the Utah Expedition as a civilian, but years later he recalled he resigned in disgust at “the continual failure of the soldiers to rescue the orphaned children.”

Forney told Lynch he was “doubtful” about the Mormons he had hired to escort him to Mountain Meadows. When Lynch reached Beaver in late March, he found the Mormons had indeed abandoned Forney, warning that if he pressed on “the people down there would make an eunuch of him.” Forney asked for help, and Lynch placed his whole party at his command, but he expressed concern that Forney had hired Mormons in the first place, “the very confederates of these monsters, who had so wantonly murdered unoffending emigrants, to ferret out the guilty parties.” It would not be the last doubt Lynch would have about the nervous Indian superintendent.

Forney's party tried to get information as they trekked south, reaching Cedar City on April 16. “But no one professed to have any knowledge of the massacre,” Rogers recalled, “except that they had heard it was done by the Indians.” Jacob Hamblin sent Ira Hatch, a talented Indian interpreter who had probably killed at least one of the Arkansans himself, to guide the men to the scene of the massacre.

“Words cannot describe the horrible picture which was here presented to us,” James Lynch wrote a few months after the mid-April visit to the massacre site. What he and the others saw in this beautiful alpine valley would haunt them to their graves: “Human skeletons, disjointed bones, ghastly skulls and the hair of women were scattered in frightful profusion over a distance of two miles.” The men found three mounds, evidence of “the careless attempt that had been made to bury the unfortunate victims.” In a ravine by the side of the road, “a large number of leg and arm bones, and also skulls, could be seen sticking above the surface, as if they had been buried there,” Rogers reported. They spent several hours burying a few of the exposed remains. “When I first passed through the place,” Rogers later wrote, “I could walk for near a mile on bones, and skulls laying grinning at you, and women and children's hair in bunches as big as a bushel.” The bones of children were lying by those of grown persons, “as if parent and child had met death at the same instant and with the same stroke.” Lynch could not forget seeing the remains of those innocent victims of “avarice, fanatacism and cruelty,” adding, “I have witnessed many harrowing sights on the fields of battle, but never did my heart thrill with such horrible emotions.”

The day after visiting Mountain Meadows, Forney and his escort reached the Mormon settlement at Santa Clara, where they found 13 of the surviving children in the custody of Hamblin, who was just beginning his legendary career as a frontiersman and Indian interpreter for explorers such as John Wesley Powell. In his recollections, Lynch claimed he and a few men might have been sent ahead in disguise to find the children and determine what kind of reception awaited Forney. Fifty years later, Lynch remembered that Hamblin claimed some of the children were being held captive by the Indians. “Produce them or we will kill you,” Lynch recalled saying while pistols and rifles were pointed at Hamblin's head. “He surrendered.” (It's a wonderful story, but none of the contemporary reports— including that by Lynch—tell it.) After Forney arrived, the men spent three days at Santa Clara while clothing was made for the children.

Eyewitnesses gave contradictory reports about the circumstances of the rescued children. “The children when we first saw them were in a most wretched and deplorable condition, ” James Lynch charged, “with little or no clothing, covered with fillth and dirt, they presented a sight heart-rending and miserable in the extreme.” U.S. Army Major James Carleton said their captors “kept these little ones barely alive.” In contrast, William Rogers reported that all the children had sore eyes but were otherwise well, and Jacob Forney believed the children were well cared for. He found them “happy and contented, except those who were sick” and insisted the orphans were in better condition than most of the children in the settlements in which they lived.

Forney rejected a number of obviously fraudulent claims to repay ransoms allegedly paid to save the children, since it was well known that the children “did not live among the Indians one hour.” He received other claims for the children's support and indignantly reported he would not “condescend to become the medium of even transmitting such claims”; however, he later authorized $2,961.77 to pay for the cost of the children's care.

With the orphans in tow, Forney proceeded to John D. Lee's home in Harmony on April 22, 1859. He had learned that Lee had some of the property of the murdered emigrants in his possession and demanded that he surrender it. On the 23rd, Lee denied he had any of the property and insisted he knew nothing about it except that the Indians took it. “Lee applied some foul and indecent epithets to the emigrants,” William Rogers reported. Lee said they slandered the Mormons “and in general terms justified the killing.”

Forney's conduct while visiting Lee astounded his escort, who had refused “to share the hospitality of this notorious murderer—this scourge of the desert,” Lynch swore. He was outraged that Forney accepted Lee's hospitality, despite the statements of the surviving children, who identified Lee as one of the killers. Lee agreed to accompany Forney to Cedar City and discuss the matter of the massacre with other Mormon officials, but on the way he rode ahead and disappeared. The leaders in Cedar City proved no more helpful in tracking down the stolen property. Frustrated and outraged, Forney's party picked up three additional survivors and headed north with 16 orphans.

Meanwhile, both the U.S. Army and Federal Judge Cradlebaugh had launched their own investigations of the murders. In mid-April, Brig. Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, commander of the Department of Utah, ordered one company of dragoons and two of infantry to proceed to Santa Clara to protect travelers on the road to California, investigate reported Indian depredations and provide an escort for the Army paymaster who was on his way to Camp Floyd with a large supply of “spondulicks,” as Utah's Valley Tan reported—back pay in gold, worth a rumored half-million dollars. Johnston then ordered the “Santa Clara Expedition” to provide protection for Judge Cradlebaugh, who was on his way to investigate the crime and, if possible, arrest the murderers.

As Forney marched north, Kanosh, chief of the Pahvants, informed him that some Indians had told him there were two more children saved from the massacre than Hamblin had collected. The information was not deemed very reliable, but after meeting the troops from Camp Floyd at Corn Creek, Cradlebaugh swore in William Rogers as a deputy U.S. marshal, and Forney sent him back south to see if he could find any other children.

Rogers soon learned that one child was at a remote settlement named Pocketville. He sent Hamblin to recover the orphan, “a bright-eyed and rosy-cheeked boy, about two years old,” who proved to be Joseph Miller, youngest son of Joseph and Matilda Miller. Rogers “inquired diligently” for the second child but learned nothing. Despite a host of legends about a surviving child who remained in southern Utah, all reliable evidence indicates that the federal officials successfully recovered every surviving child.

The orphans and their ages at the time of the massacre included the children of George and Manerva Baker: Mary Elizabeth, 5; Sarah Frances, 3, and William Twitty, 9 months; of Alexander and Eliza Fancher: Christopher “Kit” Carson, 5, and Triphenia D., 22 months; of Joseph and Matilda Miller: John Calvin, 6; Mary, 4, and Joseph, 1; of Jesse and Mary Dunlap: Rebecca J., 6; Louisa, 4, and Sarah Ann, 1; of Lorenzo Dow and Nancy Dunlap: Prudence Angeline, 5, and Georgia Ann, 18 months; of Peter and Saladia Huff: Nancy Saphrona, 4; of Pleasant and Armilda Tackitt: Emberson Milum, 4, and William Henry, 19 months; and of John Milum and Eloah Jones: Felix Marion, 18 months. To his credit, Forney quickly determined that “none of these children have lived among the Indians at all.” He found them “intellectual and good looking” with “not one meanlooking child among them.”

In late June 1859, the Salt Lake probate court appointed Jacob Forney guardian of the orphans with the power “to collect and receive all property belonging to the murdered Emigrants.” Forney still hoped to recover some of the wealth looted from the Arkansans, but he and his successors failed to reclaim a single nickel stolen from the Fancher party. Forney's craven behavior with John D. Lee disgusted James Lynch, who swore out an affidavit that called the agent a “veritable old granny.” Lynch accused Forney of assisting the coverup of the crime by undercutting the authority of federal officials like Judge Cradlebaugh by arousing “a feeling of resistance to his authority among the guilty murderers.”

Brigham Young followed the federal investigation closely. In early May, he groused that Congress had appropriated $10,000 and appointed two commissioners to return the orphans to their relatives. “What an expensive and round about method for transacting what any company for the States could easily attend to at any time, and with trifling expense,” he complained.

General Johnston, however, was taking no chances with the survivors' safety, and he assigned two companies of the 2nd Dragoons to escort the orphans to Fort Leavenworth. As “an act of humanity,” the firm of Russell, Majors & Waddell (which would start the Pony Express in the spring) offered the children free transportation in their freight wagons, but Johnston provided more comfortable spring wagons. Forney hired five women to accompany the “unfortunate, fatherless, motherless, and pennyless children” and made sure they had at least three changes of clothes, plenty of blankets, and “every appliance” to “make them comfortable and happy.”

Forney took two of the survivors, John Calvin Miller and Emberson Milum Tackitt, to Washington, D.C., in December 1859 to provide their “very interesting account of the massacre” to the government. The next day, Brigham Young's Washington agent reported that Forney had given the Mormon version of the massacre and would “be of service.” Young immediately responded that if Forney continued to be a “friend of Utah,” he would not lose “his reward.”

Interestingly, no record of what the two boys told federal officials survives, but even “Old Granny” had seen enough. Forney reported in September 1859 that he began his inquiries hoping to exonerate “all white men from any participation in this tragedy, and saddle the guilt exclusively on the Indians.” But it simply wasn't so. “White men were present and directed the Indians,” he concluded. Forney named the “hell-deserving scoundrels who concocted and brought to a successful termination” the mass murder: Stake President Isaac Haight, Bishop Philip Klingensmith, Branch President John D. Lee, Bishop John Higbee and Forney's own trusty guide, Ira Hatch. He gave their names to the attorney general, but nothing was done to bring the murderers to justice before the Civil War broke out—and nothing would be done for a dozen years.

William C. Mitchell, who was an Arkansas state senator, had picked up the other 15 children, who included his granddaughters Prudence Angeline and Georgia Ann Dunlap (but not his infant grandson, who was among the dead), at Fort Leavenworth in late August 1859, and on September 15, friends and relatives gathered at Carrollton, Ark., to welcome the orphans home. According to the Arkansian, Mitchell told the crowd the children were “kept secreted by the Mormons” until Forney offered to pay a $6,000 ransom.

No one who witnessed the return of the children ever forgot it. Mary Baker, whose husband Jack had died at the Meadows, took charge of her three grandchildren. “You would have thought we were heroes,” Sarah Frances “Sallie” Baker recalled in 1940. “They had a buggy parade for us.” Her grandmother gave each of the children a powerful hug. The children arrived home not long before Confederate guns opened fire at Fort Sumter, and Arkansas witnessed some of the most brutal conflict of the Civil War. Despite the turmoil, all the children found homes with relatives, who raised them as best they could.

According to John D. Lee, Brigham Young said that the government took the children to St. Louis and sent letters to their relatives to come for them. “But their relations wrote back that they did not want them—that they were the children of thieves, outlaws and murderers, and they would not take them, they did not wish anything to do with them, and would not have them around their houses.” However unreliable Lee's quote might be, a generation of Mormon historians repeated the slander that most of the children wound up in a St. Louis orphanage.

Efforts continued well into the 20th century to win some kind of compensation for the survivors of Mountain Meadows, but nothing was ever done. For the 17 orphans, the pain of their loss never went away. “I remember I called all of the women I saw `Mother,'” Sallie remembered. “I guess I was still hoping to find my own mother, and every time I called a woman `Mother,' she would break out crying.”

None of the Mountain Meadows orphans had bleaker prospects than Sarah Dunlap, who was only 1 year old when a gunshot wound almost severed her arm during the massacre. An eye disease acquired in southern Utah left her virtually sightless. After returning to Arkansas, she was educated at the school for the blind in Little Rock and settled with her sister Rebecca in Calhoun County.

James Lynch wandered the world as a mining expert, but he never lost touch with the orphans. After retiring, Lynch visited his old charges in Arkansas, who greeted him “as a returned father.” The old frontiersman found Sarah Dunlap, now “a cultured lady of 34 years,” and he soon “wooed and won” Miss Sarah. The couple were married on December 30, 1893, when the groom was 74. Lynch ran a store in Woodberry, and Sarah taught Sunday school. They eventually moved to Hampton, where Sarah died in 1901. Her ornate gravestone and vault were “proof of the tenderness that James felt for Sarah.” For decades the community recalled how Captain Lynch “never tired of telling how he rescued her from the Mormons.”

Lynch died about 1910 and was buried next to his wife in an unmarked grave. His fellow Masons conducted his funeral, the Arkansas Gazette recalled, “the likes of which have never again been seen in these parts.” The survivors of Mountain Meadows never forgot “the brave, daring and noble Capt. James Lynch,” but he rested in the unmarked grave until March 21, 1998, when the Arkansas State Society Children of the American Revolution dedicated a monument to his memory.

Will Bagley,who operates the Prairie Dog Press in Salt Lake City, is the author of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (see interview in “Reviews” in the December 2003 Wild West) and has a second book about the massacre, Innocent Blood, in the works. Bagley was also one of the people interviewed for a Mountain Meadows episode—coproduced by Bill Kurtis and Paul Andrew Hutton, and scheduled to air in late December 2004—of the History Channel's Investigating History series. Also recommended for further reading: The Mountain Meadows Massacre, by Juanita Brooks.

September Dawn movie recounts tragedy of local women’s ancestors

By Keith Purtell

Muskogee Phoenix

Phoenix Staff Writer

For most people, 9/11 refers to the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

For Muskogee residents Doris Peavler, 74, and Sue Staton, 70, it is a reminder of another Sept. 11 — Sept. 11, 1857, the date of the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

The massacre is the real story behind the movie “September Dawn,” which is now showing at Arrowhead Mall 10.

Approximately 120 emigrants passing through southwest Utah Territory died in the massacre. They were part of a wagon train were traveling from Arkansas to California. They were killed by Mormon militiamen with the help of local Paiute Indians.

Peavler and Staton had ancestors who were targeted in the massacre. Some survived, but most were killed.

“My great-grandmother, Sara Frances Baker, was among 13 members of the Baker family headed west with the wagon train,” Peavler said. “She said she was sitting on her father’s lap when something, a bullet or an arrow, tore through her ear and killed her dad. Then she turned around and saw her mother tumbling out of the back of the wagon, and she knew she was shot.”

Peavler’s great-grandmother was 3 at the time. She was among 16 or 17 young children who survived.

After an initial attack, the wagon train circled and held off the militiamen for several days. On Sept. 11, militia major, John D. Lee, approached the wagon fort under a white flag. He offered safe passage to nearby Cedar City on the condition that the pioneers give up their possessions and surrender their weapons.

As agreed, the youngest children and wounded left first in two wagons, followed by women and children on foot. The men and older boys filed out last, each escorted by an armed militiaman. The group marched for approximately a mile until, at a prearranged signal, each militiaman turned and shot the emigrant next to him. Indians rushed from their hiding place to attack the women and children.

Peavler suspects LDS church President Brigham Young was involved in the bloodbath.

“We definitely believe nothing would have happened without Brigham Young,” she said. “No Mormon would make a move without his approval.”

Peavler said her grandmother Baker never showed any negative feelings about the tragedy.

“She was soft-spoken and kind all of her life,” Peavler said.

The children who survived were taken in by local Mormon families. Peavler and Staton both say children who were siblings were separated. Although the government retrieved the children a year and a half later, Peavler believes the Mormons kept one child. She said her great-grandmother was walking down a street and saw her sister on the other side. The girl ran across the street and the two embraced, then adults pulled them apart. She never saw her sister again.

In the 1980s, there was an effort to bring together descendants of the survivors and descendants of those who participated in the massacre. Mormon President Gordon B. Hinckley supported the effort. One step was rebuilding the monument at the massacre site. During the construction, more victims’ bones were discovered.

Peavler was involved in the attempted reconciliation and says it went very well until the conclusion.

“When the monument at the site was rebuilt, he (Hinckley) was making a speech at the dedication,” she said. “At the very end, he said, ‘But we didn’t do it.’”

Staton’s surviving ancestor was her great-grandmother, Nancy Saphrona Huff, age 4. Staton criticized both those who killed the pioneers and the lack of remorse by current LDS church leaders.

“They killed these people for the booty; it was one of the richest wagon trains that ever went west,” she said. “A lot of those who did the killing went kind of crazy afterwards. One man died screaming.”

By August 1859, Jacob Forney, superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, had retrieved the children from Mormon families housing them. They were then returned to their relatives in Arkansas.

Another of Staton’s ancestors was part of the Forney’s response to the incident.

“My great-grandfather went in with the army to get the kids back,” she said. “Even though they had killed all those people, taken their possessions and taken the children, they charged the government for the time they had them. I believe it was $286 per child.”

Staton said the LDS church has not done enough to take responsibility for the tragedy.

“After 150 years, they have never apologized,” she said. “The site of the massacre is controlled by the Mormon church. It should become a national monument.

September Dawn: Criticism or Sabotage?

By

Ken Eliasberg

FrontPageMagazine.com

9/3/2007

A few months ago, I had an opportunity to attend a pre-opening screening of the film, September Dawn, a movie based on an unpleasant event that occurred 144 years prior to 9/11: the massacre by a group of Mormons of a wagon train of Christians on their way to California. The massacre occurred in Mountain Meadow, Utah, on September 11, 1857. I found the film to be artistically pleasing, theatrically well done, and, based on my less-than-exhaustive research, historically correct. I had the opportunity to view it on two occasions before its official release on August 24th. After speaking to the star and the director, I got a very good picture of the thinking that went into the decision to make the movie, and it was clear to me, no matter how prudent that decision may have been, anti-Mormon bias was never a consideration. Indeed, the makers of the film and I have great respect for the Mormon religion, the Mormon community, and the positive contribution that both have made to America. It was realized at the outset that the subject matter was sensitive and would be made more sensitive by virtue of the fact that a Mormon might be a candidate for the presidency (although this fact was not known at the time the initial decision to make the film was made).

Nonetheless, it was anticipated that the film might be judged based on its artistic features, its historical accuracy, and, hopefully, on its contemporary relevance, i.e., that all religions have, over the course of their existence, trafficked in intolerance from time to time. And, in this vein, we are now dealing with a strain of religious fanaticism that threatens our very existence. It was hoped that the film might drive this message home and highlight the need to maintain a constant vigil against such fanaticism. I repeat, there was never even the slightest measure of animus towards Mormons felt or expressed. And, I have always personally felt a sort of allegiance to the Mormon Community.

While I did not expect the Mormon Community to be enthusiastic about the film, as noted, I hoped that, in view of their having now become part of America’s mainstream, they would allow the film to be judged on its merits as an artistic undertaking and not a political statement of any kind. However, the commonality of certain language contained in a number of reviews have caused me some concerns in this regard. Specifically, the expression “ham-fisted,” or similar derivation thereof, while not unusual, is certainly not apt to appear in more than one or two criticisms of almost any particular effort; yet it appears in more than a dozen reviews of this movie, all published on the same day. It has been suggested this abundance strains any notion of mere coincidence, especially due to the fact that several noted film critics such as Jeffrey Lyons, and Rex Reed praised the film without hesitation. Even Michael Medved, while disapproving of the subject matter, praised the director, Christopher Cain, and the star, Jon Voight, for their respective talents. Indeed, Medved called both of them “some of the good guys in Hollywood.”

While the Mormon hierarchy denies any effort to directly or indirectly sabotage the film, it seems possible much of the criticism dealing with the film is derived from some common blueprint. Perhaps the suggestion is wrong – indeed, I sincerely hope that it is – but, while not being prone to embrace conspiratorial theories, I can understand those who question coincidence in matters of this nature. However, any effort to suppress speech in such a manner would not be in keeping with the thinking of friends of mine in the Mormon community. No matter how upset they might be with what they considered to be an unfair criticism of their religion, they are Americans first and Mormons second. As a consequence, they respect our freedoms, particularly freedom of expression. They would grit their teeth and let the film rise or fall on its artistic merits, secure in the knowledge that it is merely a film and their religion is more than strong enough to withstand any criticism – accurate and profound or unfair and derivative. And, again, no such criticism of the present day LDS Church was ever intended. Moreover, it concerns me that members of a great religion, such as Mormonism, may feel the need to sabotage a film in order to preserve their version of history.

I hope that this notion is mistaken, and that there is no effort on the part of the Mormon establishment to do this film in. If there is such an effort, I have to believe it emanates from certain individuals who are acting on their own, who have so little faith in the power of their religion that they think a mere film about one isolated historic incident could do it harm.

Mormons have historically been committed to American rights and values. They know freedom of expression is not to be taken lightly.

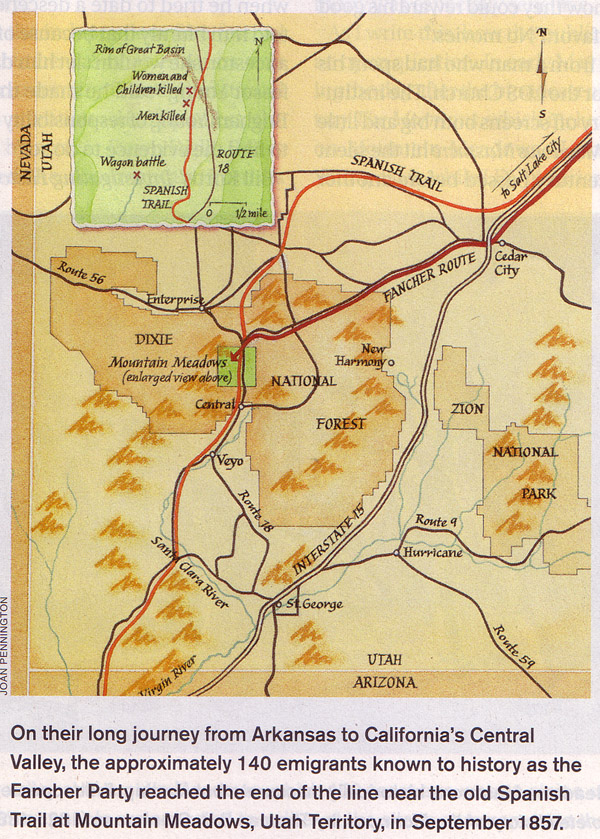

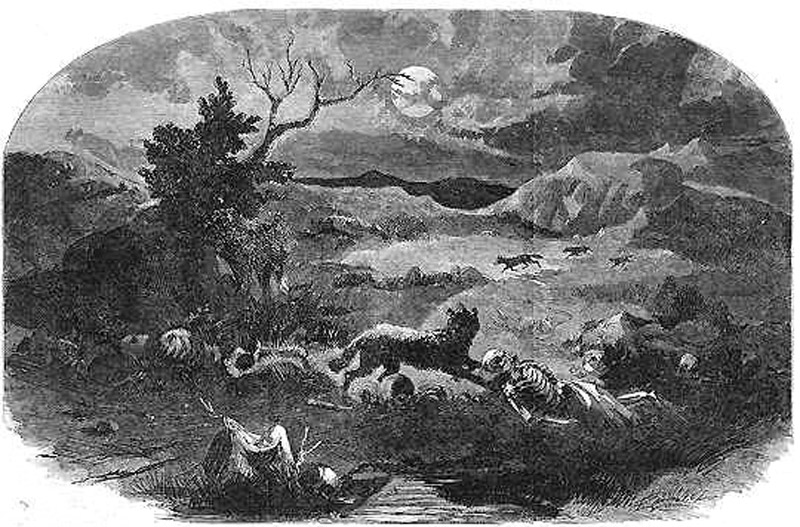

Sketch of the site of the 1857

Mountain Meadows Massacre

(from the cover of the August 13, 1859 Harper's Weekly)

"The scene was one too horrible and sickening for language

to describe. Human skeletons, disjointed bones, ghastly skulls and

the hair of women were scattered in frightful profusion over a distance

of two miles." (1859 report)

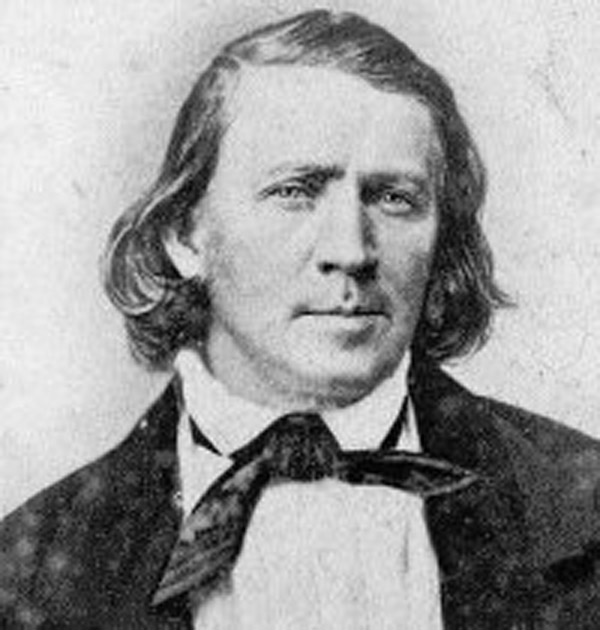

The Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857 and the Trials of John D. Lee

by Douglas O. Linder (2006)

Called "the darkest deed of the nineteenth century," the

brutal 1857 murder of 120 men, women, and children at a place in

southern Utah called Mountain Meadows remains one of the most

controversial events in the history of the American West. Although

only one man, John D. Lee, ever faced prosecution (for what probably

stands as one of the four largest mass killings of civilians in United

States history), many other Mormons ordered, planned, or participated in

the massacre of wagon loads of Arkansas emigrants as they headed through

southwestern Utah on their way to California. Special controversy

surrounds the role in the 1857 events of one man,

Brigham Young, the

fiery prophet of the Church of Latter-day Saints who led his embattled

people to the "promised land" in the valley of the Great Salt

Lake. What exactly Brigham Young knew, and when he knew it, are

questions that historians still debate.

The tragedy in Mountain Meadows on September 11--a date that would later

come to stand for another senseless loss of life--can only be understood

in the context of the colorful history of the most important

American-grown religion, Mormonism. Today, Mormonism has gone

mainstream and Mormons seem to be just one more strand among many in the

nation's religious fabric. Mormonism, however, as it existed in

the mid-nineteenth century, was an altogether different matter.

Brigham Young's provocative communalist religion endorsed polygamy,

supported a theocracy, and advocated the violent doctrine of "blood

atonement"--the killing of persons committing certain

sins as the only way of saving their otherwise damned souls. It is

not surprising that practicioners of such a religion might grow

suspicious of persons outside of their religious community, nor should

it be surprising that non-Mormons living in, or traveling through, the

very Mormon territory of Utah might feel like "strangers in a strange

land."

In July 1847,

seventeen years after Joseph Smith and a group of five other men founded

the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New York and three

years after an Illinois lynch mob killed Smith, Brigham Young and

his band of followers entered Salt Lake valley. When a territorial

government was formed in Utah in 1850, Young, the second head of the

Church of Latter-day Saints, became the territory's first

governor. The principle of "separation of church and state"

carried little weight in the new territory. The laws of the

territory reflected the views of Young. In a speech before

Congress, federal judge and outspoken Mormon critic

John Cradlebaugh said,

"The mind of one man permeates the whole mass of the people, and

subjects to its unrelenting tyranny the souls and bodies of all.

It reigns supreme in Church and State, in morals, and even in the

minutest domestic and social arrangements. Brigham's house is at once

tabernacle, capital, and harem; and Brigham himself is king, priest,

lawgiver, and chief polygamist."

Tensions between federal officials and Mormons in the new territory

escalated over time. Historian Will Bagley, author of

Blood of the Prophets: Brigham

Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, wrote

that "the struggle often resembled comic opera more than a political

battle." According to Bagley, "As both sides talked past each

other, hostile rhetoric fanned the Mormons resentment of

government. From their standpoint, they had patiently endured two

decades of bitter persecution with great forbearance, but their patience

with their long list of enemies had worn thin." As early as 1851,

Governor Young said in a speech, "Any President of the United States who

lifts his finger against these people shall die an untimely death and go

to hell!"

When drought and grasshopper infestations produced desperate economic

conditions in Utah (or Deseret, as the Mormons called the territory),

Brigham Young concluded that the problem stemmed from a loss of

righteousness among his people. In early 1856, Young launched the

Reformation, a campaign to arouse religious consciousness. Mormon

leadership urged spiritual repentance and rebaptisms. All those

unwilling to make the necessary religious sacrifices were invited to

leave Utah. The most troubling aspect of the Reformation was its

obsession with the doctrine of blood atonement. Young asked his

followers to kill Mormons who committed unpardonable sins: "If our

neighbor...wishes salvation, and it is necessary to spill his blood upon

the ground in order that he be saved, spill it." While Young aimed

his fiery words about blood atonement at Mormons who committed serious

sins, his speeches undoubtedly contributed to a growing culture of

violence. The Reformation might have had a spiritual goal, but it

fueled a fanaticism that led to the tragedy at Mountain Meadows.

In 1857, conflict between the Mormon leadership and Utah and the federal

government reached the boiling point. Worried that a federal army

might be sent to the territory, the Mormon-dominated Utah legislature

enacted legislation in January reactivating the territorial militia,

called the Nauvoo Legion. Federal officials in Utah complained of

harassment and destruction of records by Mormon citizens. On April

15, 1857, a federal judge, the territorial surveyor and the U. S.

marshal (all the federal officials in Utah except one Indian agent) fled

the state, convinced that they were about to be killed. President

James Buchanan responding by ordering an army to Utah to quell what he

called a "rebellion."

Buchanan's order alarmed Utah's Mormon population, who saw it as nothing

less than a threat to the existence of their religion. Past

persecution experienced by Mormons in the Midwest made the danger seem

especially real. Church officials referred to Federal officials

and the U. S. army as "enemies," and Utahans readied for what many saw

as a life-or-death struggle for their faith. Young embarked on an

effort to rally Indian support for the Mormon cause--support that he saw

as potentially critical in the battle to come.

Meanwhile, several extended families left Arkansas by wagon train on

what they planned to be their long emigration to southern

California. Unfortunately for the groups of families (which came

to be called "the Fancher party"), a revered Mormon apostle (and the

great-great grandfather of 2008 Republican presidential candidate Mitt

Romney), Parley Pratt, was murdered in western Arkansas within two weeks

of their departure. News of the Pratt murder, committed by a

non-Mormon angered over Pratt's taking of his wife, soon reached Utah,

and greatly inflamed local hostility toward non-Mormons. When

further word reached Salt Lake in July 1857 that the army was headed its

way, Utah became a place hungry for retribution.

On September 1, 1857, Brigham Young met in Salt Lake City with southern

Indian chiefs. According to an entry in the diary of Dimick

Huntington, Young's brother-in-law who was present at the meeting, Young

encouraged the Indians to seize "all the cattle" of emigrants that

traveled on the "south route" (through southern Utah) to

California. (The journal entry actually says Young "gave" the

Paiute chiefs the emigrant's cattle.) The meeting increased the

likelihood of a violent encounter between Indians and emigrants,

something Young apparently saw as a useful shot across the federal

government's bow. In fact, Young had been working on such a plan

even before his September 1 meeting, having sent apostle

George A. Smith south

with instructions to let the Indians know that Young considered

emigration through Utah a threat to the well-being of both Mormon and

Indian residents of the territory.

The same day that Young talked with Paiute leaders,

the Fancher Party,

consisting of about 140 Arkansans, camped about seventy miles north of

Mountain Meadows. On the Fancher party's way through Utah, rumors

spread that some of its members participated in the killing of Parley

Pratt and the lynching of Joseph Smith in Illinois. John D. Lee, a

Mormon living in southern Utah, believed the stories to be true: "This

lot of people had men amongst them that were supposed to have held kill

the prophets in the Carthage jail." (Later, in attempts to

rationalize the slaughter, Utahans would accuse the Fancher party of

committing all sorts of manufactured sins and depredations: "tormenting

women," swearing, insulting the Mormon Church, brandishing

pistols, and even poisoning cattle. There is virtually no evidence

to support any of these charges. Undoubtedly, the Fancher party

understood it was not welcome in the territory and simply wanted to get

out as fast as possible.)

On September 4, Cedar City was gripped in the white heat of fanaticism

as the Fancher train rolled into the southwestern Utah town. The

wagon train's imminent arrival had prompted

Isaac Haight, second

in command of the Iron Brigade (the Nauvoo Legion's force in southern

Utah) and President of the Cedar City Stake of Zion (the highest Mormon

ecclesiastical official in southern Utah), to call a meeting to discuss

the course of action to be taken against the emigrants. According

to Lee's later account of the meeting, Haight said it was "the will of

all in authority" to arm Paiute and incite them to "kill part or all" of

the party. Haight sent Indian interpreter

Nelphi Johnson off on

a mission to "stir up" the Indians so that they might "give the

emigrants a good hush." Haight shed no tears for the party's fate,

telling Lee, "There will not be one drop of innocent blood shed, if

every one in the damned pack are killed, for they are the worse lot of

outlaws and ruffians that I ever saw in my life."

Sunday, September 6 was a day for dramatic speech making at Mormon

services around Utah. In Salt Lake City, Brigham Young took the

occasion to declare that the Almighty recognized Utah as a free and

independent people, no longer bound by the laws of the United

States. In Cedar City, meanwhile, Isaac Haight told those gathered

at the morning service that "I am prepared to fee to the Gentiles the

same bread they fed to us. God being my helper, I will give the

last ounce of strength and if need be my last drop of blood in defense

of Zion." That Sunday evening, the Fancher party crossed over the

rim of the Great Basin and encamped at a place called

Mountain Meadows.

The next morning's calm at the meadows was interrupted by gunfire. A

child who survived the attack wrote later, "Our party was just sitting

down to a breakfast of quail and cottontail rabbits when a shot rang out

from a nearby gully, and one of the children toppled over, hit by a

bullet." The shots came from forty to fifty Indians and Mormons

disguised as Indians. The well-armed emigrants returned

fire. Soon the gun battle turned into a siege. Meanwhile, in

Cedar City, Isaac Haight, responding to pressure from Mormons lacking

enthusiasm for the attack on the emigrants, sent a courier on a

600-mile trip (that

will take six days, round trip) to inform Brigham Young of the situation

at Mountain Meadows and ask his guidance about what to do next.

Over the next three days, Mormon reinforcements, totally about 100 men,

continued to arrive at the battle scene. Men on horseback carried

messages back to Haight, and his immediate superior in the

Nauvoo Legion and head

of southern Utah forces,

William Dame.

Dame reportedly reiterated his determination to not less the emigrants

pass: "My orders are that all the emigrants [except the youngest

children] must be done away with." On September 10, the messenger

send to Salt Lake City arrived and handed Haight's letter to

Young. Young, according to published Mormon reports, sent the

messenger back to Haight with a note telling him to let the Indians "do

as they please," but--as for Mormon participation in the siege--if the

emigrants will leave Utah, "let them go in peace." The message

will be too late.

By September 11, Legion officers had devised a plan for ending the

stand-off. Most of the

Paiutes had left after

growing weary of the siege and could play no role in the bloody

conclusion. The plan was devious, but effective.