TRAITOR AMERICAN MUSLIM CLERICS

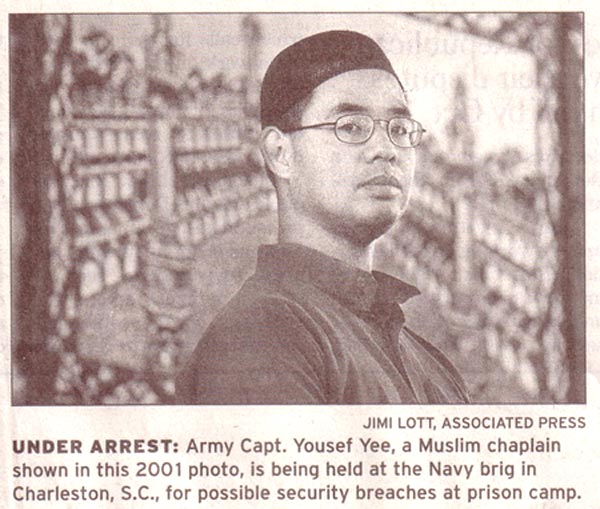

The charges were dropped so that classified information would not be released.

Yemeni-American Cleric Calls for Violence in US

18 March 2010

Heather Murdock

Voice of America

A U.S.-born radical cleric linked to shootings at a U.S. army base and

the failed bombing of a U.S. plane, is calling for a violent uprising

against the United States in an audiotape Wednesday.

On his Web site, Anwar al-Awlaki, a soft-spoken American-born Yemeni

cleric calls Nidal Hassan, the man accused of killing 13 people in Fort

Hood, Texas last fall a "hero." But after Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab was

arrested attempting to blow up a plane over Detroit on Christmas day,

al-Awlaki denied any connection to the plot, and said he does not

support violence against civilians.

This week, it appears al-Awlaki has changed his mind. In a tape

released to CNN, al-Awlaki once again reached out to young American

Muslims, and called for violence against the U.S.

"To the Muslims in America, I have this to say: How can your conscience

allow you to live in peaceful coexistence with the nation that is

responsible for the tyranny and crimes committed against your own

brothers and sisters?" he asked.

The U.S. and Yemeni governments say al-Awlaki is an al-Qaida member,

recruiter and spiritual adviser. He is currently hiding out in Yemeni

tribal lands, far from the reach of the government. Al-Awlaki's

followers include two of the September 11th hijackers, and more

recently, Sharif Mobley, an American suspected of plotting terror

attacks with al-Qaida from Yemen.

Yemenis say he is little known in his home country, because he grew up

in America, and preaches in English. But on the Internet, he is

the jihadist equivalent of a pop-star. His audio lectures have gone

viral, as he tries to radicalize young Westerners by tugging at their

heartstrings.

"Palestinian children, charging at the soldiers full speed, armed with

nothing but rocks and wearing nothing but trousers and T-shirts are

cowards? I fail to understand that," he added.

This comes at a time when authorities are worried by an increasing

number of Westerners arrested in connection with al-Qaida, including a

Pennsylvania woman arrested last week known as "Jihad Jane." In the

past two years, more than a dozen Americans have been arrested for or

identified as supporters of violent anti-Western jihad.

And after months of near-silence, Anwar al-Awlaki is once again is

trying to inspire this trend, or at least re-claim his reputation as

"the Osama bin Laden of the Internet."

Born in U.S., a Radical Cleric Inspires Terror

By SCOTT SHANE

The New York Times

November 18, 2009

WASHINGTON — In nearly a dozen recent terrorism cases in the United

States, Britain and Canada, investigators discovered the suspects had

something in common: a devotion to the message of Anwar al-Awlaki, an

eloquent Muslim cleric who has turned the Web into a tool for extremist

indoctrination. Skip to next paragraph

Mr. Awlaki, 38, the son of a former agriculture minister and university

president in Yemen, has never been accused of planting explosives

himself. But experts on terrorism believe his persuasive endorsement of

violence as a religious duty, in colloquial, American-accented English,

has helped push a series of Western Muslims into terrorism.

Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan, the Army psychiatrist charged with killing 13

people at Fort Hood, Tex., on Nov. 5, is only the latest suspect

accused of perpetrating or plotting violence to be linked to the cleric.

In 2006, for example, a group of Canadian Muslims listened to Mr.

Awlaki’s sermons on a laptop a few months before they were charged with

plotting attacks in Ontario to have included bombings, shootings,

storming the Parliament Building and beheading the Canadian prime

minister.

In 2007, one of six men later convicted of plotting to attack Fort Dix

in New Jersey was picked up on a surveillance tape raving about Mr.

Awlaki’s audio clips. “You gotta hear this lecture,” said the plotter,

Shain Duka. Mr. Duka called the cleric’s interpretation of Muslim

duties “the truth, no holds barred, straight how it is!”

Last year, Mr. Awlaki exchanged public letters on the Web with Al

Shabaab, a Somali Islamist group that has attracted recruits among

young Somali-Americans living in Minnesota. The message from Al Shabaab

praised the cleric as “one of the very few scholars” who “defend the

honor of the mujahideen.”

“Allah knows how many of the brothers and sisters have been affected by your work,” it said.

Evan Kohlmann, a counterterrorism researcher who has testified in

terrorism trials in the United States and United Kingdom, said Mr.

Awlaki’s work had also turned up in cases in Chicago and Atlanta and in

at least seven in the United Kingdom.

“Al-Awlaki condenses the Al Qaeda philosophy into digestible,

well-written treatises,” Mr. Kohlmann said. “They may not tell people

how to build a bomb or shoot a gun. But he tells them who to kill, and

why, and stresses the urgency of the mission.”

For at least a decade, counterterrorism officials have had a wary eye

on Mr. Awlaki, an American citizen now living in Yemen. His contacts

with three of the Sept. 11 hijackers, at mosques where he served in San

Diego and Falls Church, Va., remain a perplexing mystery about the 2001

attacks, said Philip Zelikow, who was executive director of the

national 9/11 commission.

But in recent years, concerns have focused on Mr. Awlaki’s influence

via his Web site, his Facebook page and many booklets and CDs carrying

his message, including a text called “44 Ways to Support Jihad.”

Mr. Awlaki’s current site, www.anwar-alawlaki.com, went offline after

he was linked to Major Hasan, apparently because a series of Web

hosting companies took it down. The home page on Wednesday displayed a

Muslim greeting and a promise: “The Web site will be back to normal

with a few days time.”

Starting late last year, Major Hasan sought religious advice from the

cleric in e-mail messages intercepted by American intelligence. He had

seen Mr. Awlaki preach at the Virginia mosque in 2001.

In July, the month Major Hasan was transferred to Fort Hood, Mr. Awlaki

posted a blistering attack on his Web site denouncing Muslim soldiers

who would fight against other Muslims, a conflict that preoccupied

Major Hasan, who was facing deployment to Afghanistan.

“What kind of twisted fight is this?” Mr. Awlaki wrote on “Imam Anwar’s

Blog.” A Muslim soldier who follows orders to kill Muslims, he wrote,

“is a heartless beast, bent of evil, who sells his religion for a few

dollars.”

After the Fort Hood shootings, Mr. Awlaki called Major Hasan a hero.

“The only way a Muslim could Islamically justify serving as a soldier

in the U.S. Army,” he wrote on his blog, “is if his intention is to

follow the footsteps of men like Nidal.”

The question of what to do about terror propagandists like Mr. Awlaki

is complex. His writings, though they encourage violence, are protected

by the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech, legal authorities

say.

Moreover, even as they fuel extremism, Web sites like his can be a

valuable counterterrorism tool, because intelligence analysts use them

to track those who, like Major Hasan, visit a site, post comments or

e-mail its creators.

“The debate has gone on for a long time: take these sites down or leave

them up to gather information,” said Brian Fishman, a consultant to

several government agencies on terrorism.

Mr. Awlaki was born in New Mexico in 1971, where his father, Nasser

al-Awlaki, was studying agricultural economics. After studying Islam in

Yemen, Anwar, too, pursued an American education, earning a bachelor’s

degree in civil engineering from Colorado State University and a

master’s in education at San Diego State. While in San Diego, he was

arrested for soliciting prostitutes, law enforcement records show.

At a San Diego mosque where he was an imam, Mr. Awlaki met two future

hijackers, Khalid al-Midhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi. In early 2001, Mr.

Awlaki moved to the Virginia mosque, attended by Mr. Hazmi and a third

hijacker, Hani Hanjour. The 9/11 panel described the connection as

suspicious. Law enforcement officials say they strongly doubted Mr.

Awlaki knew of the plot, though they could not prove it.

While in the United States, Mr. Awlaki presented a moderate public

face. A month after the Sept. 11 attacks, as imam at Dar al-Hijrah

mosque in Virginia, he told The New York Times that he would no longer

tolerate “inflammatory” rhetoric. The article said Mr. Awlaki “is held

up as a new generation of Muslim leader capable of merging East and

West.”

Johari Abdul-Malik, imam of the Virginia mosque, said Mr. Awlaki’s

sermons were accessible, often witty explorations of Koran passages.

“We could have all been duped,” he said. “But I think something

happened to him, and he changed his views.”

One thing that happened, after he left the United States in 2002 for

London and then Yemen, was eighteen months in a Yemeni prison. He has

publicly blamed the United States for pressuring Yemeni authorities to

keep him locked up and has said he was questioned by F.B.I. agents

there.

Since his release in December 2007, his message has been even more

overtly supportive of violence. In “44 Ways to Support Jihad,” he

showed a wry awareness of intelligence agencies’ interest in him and

his writings.

“The only ones who are spending the money and time translating Jihad

literature are the Western intelligence services,” he wrote in English,

“and too bad, they would not be willing to share it with you.”

Theodore Roosevelt's ideas on Immigrants and being an AMERICAN in 1907

“In the first place, we should insist that if the immigrant who comes here in

good faith becomes an American and assimilates himself to us, he shall be

treated on an exact equality with everyone else, for it is an outrage to

discriminate against any such man because of creed, or birthplace, or origin.

But this is predicated upon the person's becoming in every facet an American,

and nothing but an American... There can be no divided allegiance here. Any man

who says he is an American, but something else also, isn't an American at all.

We have room for but one flag, the American flag.... We have room for but one

language here, and that is the English language... and we have room for but one

sole loyalty and that is a loyalty to the American people.”