THERE IS NO ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR THE BOM!

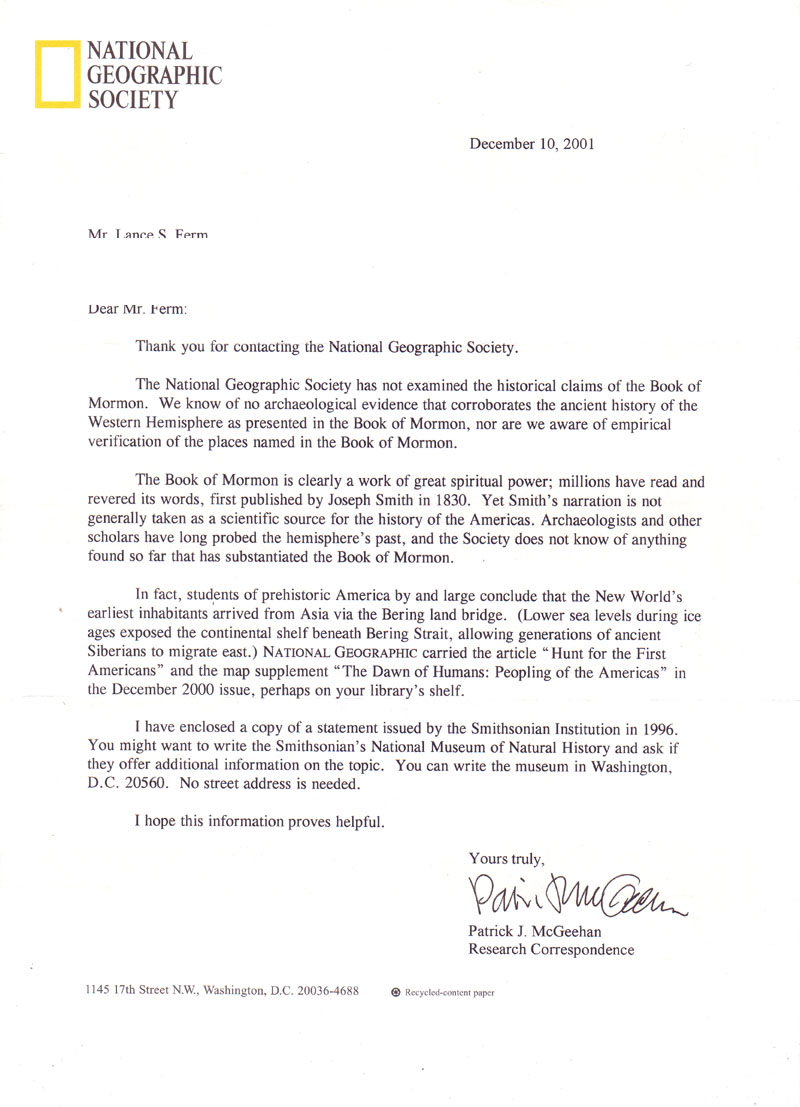

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY STATEMENT ON THE BOOK OF MORMON

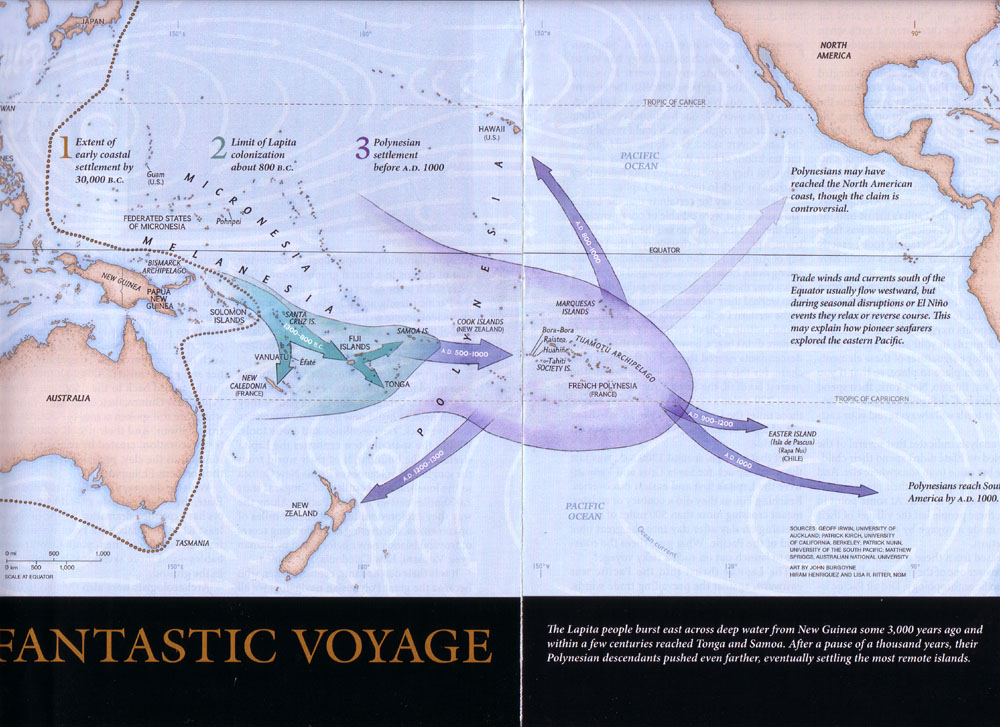

THE FICTIONAL LEHI AND NEPHI NEVER SAILED ACROSS THE PACIFIC IN 600 BCE.

ARCHEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR THE HOLY BIBLE HAS ALWAYS BEEN ABUNDANT.

HOWEVER, THE LDS CHURCH STILL PROCLAIMS THE BOM AS TRUE!

The Daily Herald

Book of Mormon

Documentary

Sunday, August 14, 2005

The new (Mormon) documentary records what (Mormon) scholars believe is the probable route followed between 600 B.C. and 589 B.C. by ancient inhabitants of Jerusalem who traveled to the Americas, as documented in the Book of Mormon, a volume of scripture sacred to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

"Journey of Faith," completed over a five-year period in Israel, Jordan, Yemen, Oman and Guatemala, is being presented to audiences for the first time on all five nights of Brigham Young University's Campus Education Week, which begins today.

The (Mormon) documentary's estimation of the course traveled by the Book of Mormon prophet Lehi and his kin is based on the best (Mormon) research available, said S. Kent Brown, a BYU professor of ancient scripture who is featured in the film and will present it to Education Week attendees.

Brown said the film -- to be marketed on DVD in Utah and elsewhere later this year by Covenant Communications -- was made primarily for Latter-day Saints, but that he believes it might be of interest even to viewers with no connection to Mormonism. "We think we've done our homework well enough," he said, "that anyone could watch it and find the account to be believable, or at least credible."

Searching for Book of Mormon Lands in Middle America

Review of Sacred Sites: Searching for Book of Mormon Lands by Joseph L. Allen

Reviewed By: John E. Clark

Provo, Utah: Maxwell Institute, 2004. Pp. 1–54

The Book of Mormon communicates clearly four fundamentals about its

setting: its lands were warm, narrow in at least one place, flanked by

"seas," and small. Many inferences flow from these facts, the most

salient being that Book of Mormon events occurred somewhere in Middle

America. But where? Dozens of correlations have been proposed over the

years, with no consensus in sight. In this essay I review two recent

proposals and consider their merits against the backdrop of adjacent

alternatives. In doing so, I presume that getting the geography right

is important for a variety of reasons and that there are clear tests

for making the determination. Here I evaluate two models in light of

geographical, archaeological, and anthropological criteria. Physical

features and city locations need to conform to the claims in the text,

sites need to date to the right time periods, and there should be

evidence (or a plausible presumption) of the cultural practices

mentioned in the Book of Mormon.

My specific objective is to evaluate Joseph L. Allen's recent

publication Sacred Sites: Searching for Book of Mormon Lands and James

Warr's A New Model for Book of Mormon Geography, a Web site copyrighted

in 2001. After a brief overview of each, I focus on the plausibility of

their major claims.

Allen's Sacred Sites

This slim hardback book—lavishly colored with images of wildflowers,

maps, sites, peoples, places, and fake artifacts—merits a glance but

not a careful read. Its substance evaporates with scrutiny. Although

Allen presents himself as an expert with forty years of research

experience, a PhD on Quetzalcoatl legends, and more than two hundred

tours to Middle America, his expertise is not evident in this

publication; this is not his best work. Outwardly, Sacred Sites has the

form of a book, but it is really an expensive promotional brochure for

a Book of Mormon tour, complete with a $400 voucher on the inside flap.

The book privileges impressions over substance and appears designed for

travelers with short attention spans and little knowledge.

Presentations are shallow, with splashes of color substituting for

cogent discussion. Sacred Sites is disappointing because it lacks an

introduction, a theme, a logical argument, cohesion, relevant and

correctly labeled illustrations, competent editing, attribution of

information to legitimate sources, complete bibliographic references,

and conclusions. Rather, its ten chapters are more akin to disjointed

journal entries for different travel stops. The publication presumes

the presence of a tour guide who can explain why the issues and

illustrations are relevant, interesting, or true. Without a guide, it

needs to be supplemented with Allen's earlier, extensive work,

Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon.1

Sacred Sites appears designed for durability and usability for those on

tour with only a few minutes per day to read. The highlight is its

cover (an impressionistic color painting of Izapa Stela 5) and the

commissioned illustrations just inside. The front endpapers feature a

colorful rendition of Allen's proposed site of Book of Mormon lands in

southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize—an area known to archaeologists

as Mesoamerica. The artwork by Cliff Dunstan conveys a 1950s pastel

watercolor look to the maps, time lines, and other graphics. On the

back endpapers one finds a chart that juxtaposes chronologies of

Mesoamerican cultures and cities and those in the Book of Mormon. Much

of the displayed chronological information, however, is imprecise. Site

histories are lengthened or shortened by a century or two to fit Book

of Mormon expectations rather than chronologies reported by

archaeologists. But the reader cannot learn this because sources for

critical information are not listed; citation oversights characterize

each chapter, and several citations listed lack essential information.

There is no indication that facts or precision matter.

Its ten chapters cover the following themes and places: sacred

geography, Lehi's landing site, the route up to Nephi, the route down

to Zarahemla, the east wilderness, the land of Bountiful, the land of

Desolation, Monte Alban, Teotihuacan, the term dark and loathsome, and

the term pure and delightsome. Allen was heavily influenced by M. Wells

Jakeman in the 1960s and tries to follow Jakeman's historic approach to

early Mesoamerica and geography.

Allen accords archaeology a major role in understanding the Book of

Mormon. On the back cover of his publication, he proclaims that "the

primary purpose of this book is to bring to life the historical and

geographical elements of the Book of Mormon. It will also show how, in

most instances, these details can lead us to Christ, which is the

ultimate purpose of the Book of Mormon." In short, Allen is marketing

spiritual experiences at sacred sites. These are powerful objectives

worth discussing. Surely the claims of capturing ancient spirituality

by retracing the steps of ancient prophets depend on being at the right

places.

Warr's New Model

Warr argues that Mesoamerica does not fit the tight specifications for

Book of Mormon lands from the text and that a much better fit can be

found in Costa Rica and adjoining countries of lower Central America.

Although his material is found on a Web site, his argument is more

booklike, coherent, and reader-friendly than Allen's book. I did not

expect to be impressed with any proposal for a Central America

correlation for Book of Mormon lands, but I was. Warr's work is worth

contemplating. He proceeds logically with all the information he can

muster from various sources. He carefully lays out the requirements for

each geographical feature and argues for placing them in Central

America rather than elsewhere. His work is broadly comparative and

competitive. He has read other proposals that place Book of Mormon

lands in the Great Lakes region, South America, or parts of

Mesoamerica, and he identifies their deficiencies.2

Warr addresses four categories of topics, arranged hierarchically and

accessible as separate topics by clicking the appropriate icon: Book of

Mormon lands, populations, cultures, and miscellaneous topics. He

considers fourteen places or topics under the category lands: the

narrow neck, seas, river Sidon, travel distances, comparison of

distances, Nephite lands as an island (however, this link is not

currently active), Cumorah, and the lands of Zarahemla, Nephi, Gideon,

Jershon, Desolation, Bountiful, and those of the Jaredites. In the

culture section, he provides an interesting comparison of Nephite and

Jaredite cultures and by so doing raises, by implication, the

unaddressed question of Lamanite culture, a topic meriting serious

investigation. Warr's miscellaneous topics cover a broad range, from

Joseph Smith's opinion of Nephite geography to the large stone balls

found in Costa Rica. The starting point for his presentation appears to

be his conviction that the narrow neck of land is the key for locating

Book of Mormon lands. As do others, Warr considers the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec, the narrow neck proposed for Mesoamerican correlations

such as Allen's, to be much too wide to meet the specifications in the

text.

The narrow neck of land is necessarily linked to the identification of

the east and west seas of the Book of Mormon account. I agree with Warr

that this neck is a key feature of Book of Mormon lands. If we could

pinpoint its location correctly, the sites for other features and

cities would eventually follow. At least six different locations for

the narrow neck have been proposed for Middle America (see fig. 1).

Identification of this key feature is the starting place in evaluating

the plausibility of different proposed geographies.

The Narrow Neck and the Sea East

For some time now, all presentations of Book of Mormon geography,

explicitly or not, have contended with John Sorenson's limited

Mesoamerica model.3

The simplification of his model shown in figure 2 illustrates principal

relationships among the lands northward and southward, the narrow neck

of land at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico, and the east

and west seas. Figure 3 demonstrates that Allen's geography shares some

features with Sorenson's, such as the location of the narrow neck of

land, but some proposed locations differ significantly in the two

proposals. James Warr rejects the Tehuantepec hypothesis and other

proposals for the narrow neck in Middle America because, in his

opinion, they do not conform to the requirements for the narrow neck

specified in the Book of Mormon. He lists at least twelve criteria for

identifying this feature:

1. It should be oriented in a general north-south direction (Alma 22:32).

2. It is flanked by a west sea and an east sea (Alma 22:32).

3. It should be located at a place where "the sea divides the land" (Ether 10:20).

4. It may have a separate feature called the "narrow pass" (or this may just be another name for the narrow neck; Alma 50:34; 52:9).

5. It could be traversed in 1 to 1 1/2 days (this would make it approximately 15–40 miles wide; Alma 22:32; Helaman 4:7).

6. It was at a lower elevation than the higher land to the south (Mormon 4:1, 19).

7. The combined land of Zarahemla and Nephi, southward from the narrow neck, was almost completely surrounded by water and was small enough that the inhabitants considered it an island (Alma 22:32; 2 Nephi 10:20–21).

8. At one time in Jaredite history the narrow neck was blocked by an infestation of poisonous snakes so that neither man nor beast could pass. (This could only occur if there were a water barrier on both sides; Ether 9:31–34). . . .

9. The city of Desolation was located on the northern portion of the narrow neck (Mormon 3:5–7).

10. Lib, a Jaredite king, built a "great city" at the narrow neck (this

may be the same as the city of Desolation; Ether 10:20). . . .

11. It should be an area which would be easy to fortify (Alma 52:9; Mormon 3:5–6).

12. The Jaredites did not inhabit the land south of the narrow neck,

but reserved it for hunting. Therefore there should be no remnants of

ancient Jaredite cities south of the isthmus (Ether 10:21). (Warr, "The

Narrow Neck of Land," with minor editorial changes and some deletions)

Choosing the Right Neck

Some of these inferences are more secure than others, but for purposes

of discussion, I take them at face value to recapitulate Warr's

criticisms of other geographies and his advocacy of his own. Warr's

principal target is the Tehuantepec hypothesis. How does it stack up

against his expectations? Tehuantepec has a few things going for it:

"It is surrounded by ancient ruins of the classical Maya and Olmec

eras. . . . The land below the isthmus (east and south) is largely

surrounded by water and could loosely be considered an island. . . . It

is at a lower elevation than the land on either side" (Warr, "The

Isthmus of Tehuantepec"). According to Warr, however, Tehuantepec fails

as the narrow neck of land on eight counts:

1. It is much too wide. It is 140 miles across and would

not be considered narrow by the average person. It could not be crossed

in 1 1/2 days by the average person, but would take 7 days at 20 miles

per day. . . .

2. It is oriented in the wrong direction. It is oriented in an

east-west direction rather than the "northward" direction described in

the Book of Mormon (Alma 22:32).

3. It is not bordered by a west sea and an east sea, but by a north sea and a south sea (Alma 22:32).

4. It does not have a recognizable feature called the "narrow pass" (Alma 50:34 and 52:9).

5. It is not located at a place where the "sea divides the land" (Ether 10:20).

6. It is unlikely that it could be completely blocked by an infestation of snakes as described in Ether 9:31–34.

7. This isthmus would be difficult to completely fortify against an invading army (Alma 52:9).

8. Assuming that the Olmec and Early Formative people of this area were

equivalent to the Jaredites, there are many of their ruins on both

sides of the isthmus. However, the Jaredites did not build cities south

of the narrow neck and preserved the land as a wilderness (Ether

10:21). This being the case, the area of Chiapas, Guatemala, etc.,

could not be the land of Zarahemla. (Warr, "The Isthmus of

Tehuantepec," with minor editorial changes)

As outlined by Warr, the deficiencies of the Tehuantepec theory are

insurmountable, but not all is as he portrays it. Some of his claims go

beyond what the text states and are shaded with cultural assumptions. I

will return to Warr's specific objections after first presenting his

proposal for the narrow neck of land on the Rivas Isthmus of Costa Rica

and Nicaragua, a narrow corridor between the Pacific Ocean and Lake

Nicaragua (fig. 4).

The Isthmus of Rivas is a low-lying strip of land between the Pacific

Ocean on the west and Lake Nicaragua on the east. On the western side

the isthmus is composed of a low range of coastal mountains paralleling

the Pacific coast. These hills reach a maximum height of 1,700 feet. A

low-lying plain, about 4 miles wide, and averaging 100 feet above sea

level, forms a corridor bordering Lake Nicaragua. . . .

In close association with the Isthmus of Rivas is the adjacent Lake Nicaragua. This lake is the largest freshwater lake in Central America and the dominant physical feature of Nicaragua. The Indian name for the lake was Cocibolca, meaning "sweet sea"; the Spanish called it Mar Dulce. It is oval in shape, has a surface area of 3,149 square miles, is 110 miles in length, and has an average width of 36 miles. It is about 60 feet deep in the center. . . . More than 40 rivers drain into the lake. . . .

How does the Isthmus of Rivas match the criteria . . . for the narrow neck of land? It is oriented in a northwest-southeast direction, bordered on the west by the Pacific (west sea), and on the east by Lake Nicaragua (east sea). Lake Nicaragua divides Pacific Nicaragua from the Caribbean side, hence "the place where the sea divides the land" (Ether 10:20). The narrow, level corridor bordering the lake would be the feature called the "narrow pass." The isthmus is narrow enough to cross by foot in a day.

The isthmus is much lower than the Guanacaste highlands, to the immediate south in Costa Rica. . . . The land mass of Costa Rica/Panama could easily be considered an "isle" and is at least 80–90% surrounded by the Pacific and Caribbean. This is something that the average Nephite would have been visually aware of. By climbing one of the taller mountains in Costa Rica, one can see the oceans on both sides, and possibly Lake Nicaragua and the isthmus as well. . . .

Considering

all these factors, it appears that there is a strong correlation

between the Isthmus of Rivas in Nicaragua and the narrow neck of land

described in the Book of Mormon. (Warr, "The Isthmus of Rivas as the

Narrow Neck of Land," with minor editorial changes)

Evaluating the Necks

Warr agrees with Sorenson and Allen that the narrow neck is an isthmus.

The principal disagreements center around the size of the isthmus and

its orientation. Most critics of Sorenson's model focus on his

interpretation of directions. Allen criticizes Sorenson's model for its

directional system but agrees with his identification of the narrow

neck, the river Sidon, Zarahemla, and Cumorah. In his major work on

Book of Mormon geography, Allen advocates two criteria that reveal his

"what-you-see-is-what-you-get" method; he phrases it as taking things

at "face value."

1. We must take the Book of Mormon at face value. To alter

its directions, as some current literature suggests, or to demand

unbelievable distances, as tradition outlines, is unacceptable.

2. We must be willing to accept existing maps at face value. To put

water where none exists today, to create a make-believe narrow neck of

land, or to alter the directions of the map confuses the issue and does

nothing to solve the problem. By following both the Book of Mormon and

the Mesoamerica map specifically, we find impressive geographical

correlations.4

Of course, there is always a possibility that surface appearances are

unproblematic, obvious, and correct, but such could only be shown

through analysis that explored other options and did not presume a

priori the validity of one's own superficial interpretation. Cultural

background passes as epistemology here, and unconvincingly so.

The specific claim of interest is that "some literature" alters

directions in the Book of Mormon or on Mesoamerican maps. This is

demonstrably untrue. Sorenson's geography is the real target here. He

has preserved the orientation of Mesoamerica in all of his arguments,

and he has not, to my knowledge, altered even a single scripture to say

that north was west or south was east. What Allen's loose accusations

appear to be trying to convey is that Sorenson does not assume that

"northward" in the Book of Mormon is obvious, so it is not something

that can be taken at "face value." The problem resides neither in the

manipulation of modern maps nor in ancient scripture but in the

rapprochement of the two.

In disagreeing with Sorenson on some issues but agreeing on others,

Allen introduces a fundamental inconsistency into his model. He wants

to have his European, north-south directions and the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec, too. If the narrow neck is indeed an isthmus between two

seas, and not a landlocked corridor as some authors have claimed, the

bodies of water that flanked it are the east and west seas mentioned in

the Book of Mormon. Warr and Sorenson are consistent here; Allen and

others who follow the Jakeman correlation are not. Notice in figure 3

that Allen's proposed east sea is not associated with his proposed

narrow neck. Allen identifies the Belize coast as the borders of the

east sea but places the narrow neck at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

several hundred miles due west. This is poor logic and modeling. He

can't have both. (He labels the sea north of this isthmus as the "place

where the sea divides the land.") Given Allen's claims for the Nephite

directional system, a more consistent position would be to have the

narrow neck at the base of the Yucatan Peninsula, as proposed by E. L.

Peay (fig. 5).5 But this neck is not narrow now, nor was it in Nephite

or Jaredite times. The Yucatan proposal has little going for it other

than being oriented north-south on the modern compass. Warr provides a

brief criticism of the Yucatan hypothesis. He lists four serious

problems; some are more serious and valid than others:

1. "There is no evidence that there ever was a 'narrow

neck' at the base of Yucatan. A theory which requires a change in

geography is suspect."

2. "There are the seas as required by the text; however, there does not seem to be a place where the 'sea divides the land.'"

3. "The Yucatan Peninsula would be a very limited 'land northward' and would not have contained the tremendous Nephite emigration that the book describes. Even more important it would not have been large enough to house the Jaredite population which inhabited the land northward and which surpassed the Nephite/Lamanite group in size. Also, there are few if any of the older Olmec era sites on the peninsula. . . ."

4. "There is no evidence of the geological changes described in the

text for the land northward, which took place at the time of the

crucifixion" (Warr, "The Yucatan Peninsula"; this material was

available in 2003 but no longer seems to appear on his Web site).

His second criticism is dubious, and most of his third is based on

unreliable population estimates and is thus invalid as proposed. The

most critical flaw for Peay's model is archaeological. There is no

trace of pre-Nephite civilized peoples in the Yucatan Peninsula.

Of the dozen requirements listed by Warr, some lack sufficient

specificity to distinguish among the different proposals for the narrow

neck. He appears convinced that he has discovered the only viable

candidate in the Rivas Isthmus—a precipitous conclusion. I consider

Warr's and Sorenson's proposals together in the following comments. The

numbers are keyed to Warr's original twelve criteria listed above.

1. General north-south direction. Sorenson's argument about directional

systems is that they are cultural and not necessarily transparent.

Soliciting directions in a sun-centered system is like asking someone

to identify the shady side of a tree. This simple request should elicit

more questions because shade pivots with the sun through the day and

across the year. That celestial-dependent directions such as east and

west are a bit sloppy—seasonally, topographically, latitudinally, and

culturally—is such an anthropological commonplace that I have

difficulty understanding why Sorenson's proposal for directions has

become so controversial. Sorenson's critics, among them Allen and Warr,

insist that directions are universal absolutes that conform to American

common sense. In this regard it is worth stressing that "common sense"

is cultural code for culturally dependent knowledge that makes little

sense outside one's own time or place. Likening scriptures to oneself

does not come with license to flatten cultural distinctions. The issue

of directions pervades all aspects of Book of Mormon geography and not

just the identification of the narrow neck. To the degree that Mormon's

descriptions of directions conform to those for rural Utah today,

Warr's proposal will prove superior to Sorenson's on this criterion—and

vice versa.

We may be tempted to think automatically that "northward" and

"southward" label directions that are the same as "north" and "south."

But "northward" signals a different concept than does "north,"

something like "in a general northerly direction." By their frequency

of using the -ward suffix, we can infer that Mormon and his ancestors

used a somewhat different cultural scheme for directions than we do.

However, we cannot tell from the Book of Mormon text exactly how their

concepts differed from ours, because all we have to work with is the

English translation provided through Joseph Smith.6

2. Flanked by a west sea and an east sea. This criterion is also

dependent on directional systems and naming, both of which make sense

only from a particular vantage point. One's point of reference is

critical. It is obvious to everyone that Mesoamerica around the Isthmus

of Tehuantepec has oceans to the north and south rather than to the

east and west. But from the point of view of the Lehites and the

Mulekites leaving Jerusalem, the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans were

eastward and westward paths to the promised land. The designations of

these seas appears to be tied to these original, arduous journeys

across oceans and the receding direction of their forfeited homeland.7

That the directional name might not be an accurate descriptor for every

inlet, bay, or stretch of beach is a different matter.

The directional trend of the two lands and the neck was generally

north-south. The east sea (six references) and the west sea (twelve

references) were the primary bodies of water that bounded this promised

land. But notice that the key term of reference is not "land north"

(only five references) but "land northward" (thirty-one references).

There is, of course, a distinction; "land northward" implies a

direction somewhat off from literal north. This implication that the

lands are not simply oriented to the cardinal directions is confirmed

by reference to the "sea north" and "sea south" (Helaman 3:8). These

terms are used only once, in reference to the colonizing of the land

northward by the Nephites, but not in connection with the land

southward. The only way to have seas north and south on a literal or

descriptive basis would be for the two major bodies of land to be

oriented at an angle somewhat off true north-south. That would allow

part of the ocean to lie toward the south of one and another part of

the ocean to lie toward north of the other.8

In terms of semantic domains, the text conveys a sense of equivalence

between the two seas, indicating that they are the same kinds of bodied

water and of similar magnitude. Sorenson's model preserves semantic

similarity, but Warr's does not. He would have one sea be the Pacific

Ocean and another a large lake.9 Many Book of Mormon "geographers"

entertain the notion that large lakes could have been called "seas,"

but these designations ignore the fact that the seas were also crossed

to get to the new "promised land." I find Sorenson's model more

consistent on this criterion than Warr's.

3.A place where "the sea divides the land." Warr's interpretation of

Lake Nicaragua as "dividing the land" is really innovative but, I

think, implausible. At best, this criterion is extremely ambiguous and

unhelpful. Most proposals I have seen argue that it is a place in the

narrow neck where the water comes in, such as a river mouth or a bay,

rather than being an inland division. This criterion does not favor

either proposal.

4.The "narrow pass." This feature is equally ambiguous and

nondifferentiating. Warr's claim that the Tehuantepec model does not

handle this is incorrect. Warr's commentary only makes sense if one

agrees with him that Sorenson's description of the narrow ridge of high

ground through the lowlands of Tehuantepec is not a legitimate

interpretation of the "narrow pass." But this is an argument about the

meaning of the text rather than over the presence or absence of a

viable, physical feature. This criterion does not favor either model.

5."The distance of a day and a half's journey for a Nephite." Warr's

proposal for the narrow neck has an advantage over all others (fig. 1

no. 4) in being significantly narrower, thus providing an easy,

"literal" reading for the short journey for "a Nephite." He argues that

this distance should be in the range of fifteen to forty miles. Warr

muddies the water extensively in his comments on his proposal by

putting restrictions in the text that simply are not there. The

"Nephite" mentioned in the Book of Mormon becomes "an average person"

or "an average Nephite" in Warr's exposition. This is probably wrong.

B. Keith Christensen argues that the context and phrasing suggest

something significantly different. He proposes a distance upwards of a

hundred miles, with the "day's journey" occurring under military

conditions and with a special courier, being at least eighteen hours of

travel per day, and probably on a horse.10 This accords with his

proposed geography shown in figure 6. Personally, I think the wider

distance crossed by military personnel a more likely interpretation. In

fairness, however, the description of distance is ambiguous and

provides ample latitude for contravening interpretations. In his effort

to resolve the problem of wide isthmuses, I think Warr has erred on the

narrow side. His narrow neck is too small. It is not even a day's

travel wide for an "average" walker on a short day. By highlighting

this one geographic feature at the expense of others, Warr fails to

account for other significant observations. For instance, Sorenson's

argument is that the narrow neck had to be wide enough that people on

the ground such as Limhi's group could pass through it without

realizing it.11 This would have been nigh impossible for the Rivas

Isthmus, given its narrow width, long length, and the advantageous

viewing conditions from its crest. Curiously, the Limhi episode did not

make Warr's list of twelve criteria, but it is very significant. In

sum, the touted scalar advantage of the Rivas peninsula over other

proposals for the narrow neck is actually a critical weakness. Like the

old Grinch's heart, the Rivas neck is several sizes too small. I give

the Tehuantepec proposal the advantage on this criterion.

Before leaving this issue, it is worth mentioning that some proposals

narrow the distance across the neck by suggesting raised sea levels in

Book of Mormon times. M. Wells Jakeman and his principal disciple, Ross

T. Christensen, argued that in Book of Mormon times the seas came much

farther inland in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, thus significantly

reducing the width of the narrow neck at this place.12 Jerry L.

Ainsworth's recent proposal (fig. 7) adopts this line of argument.13

Archaeologically, though, we know of early and late sites near the

current beach lines, so the ocean margins must have been at their

current positions by about four thousand years ago, with only minor

fluctuations of a meter or two since then. In short, recourse to

catastrophic geology will not do for slimming the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec.

6.Lower elevation than the land to the south. Both proposals do equally well with this requirement.

7.Almost completely surrounded by water. Warr muddies the water a bit

on this one, too, by claiming "that the inhabitants considered their

land an island." What the book says is that "the land of Nephi and the

land of Zarahemla were nearly surrounded by water" (Alma 22:32), being

an "isle of the sea" (2 Nephi 10:20). Sorenson clarifies that "in the

King James Version of the Bible and generally in the Book of Mormon, an

'isle' was not necessarily completely surrounded by water; it was

simply a place to which routine access was by sea, even though a

traveler might reach it by a land route as well."14 Warr scores this

criterion equally for the Rivas and Tehuantepec proposals; I agree.

This is an ambiguous requirement of little distinguishing power.

8.Serpent barrier. The description of poisonous snakes blocking passage

to the land southward in Jaredite times is one of the more unusual

claims in the Book of Mormon. I agree with Warr that the incident

indicates warm climes and favors the interpretation of the narrow neck

as an isthmus rather than a corridor. Beyond this, there is not much

that we can wring from this description. John Tvedtnes suggests that

the snakes could have been associated with drought and infestations of

small rodents,15 something that could have occurred in either area.

Poisonous snakes are probably prevalent in both proposed areas. For

now, this criterion does not favor either proposal. For his part, Allen

reads these passages metaphorically to refer to secret societies; he

claims that a literal reading is nonsensical.

And there came forth poisonous serpents also upon the face of the land,

and did poison many people. And it came to pass that their flocks began

to flee before the poisonous serpents, towards the land southward,

which was called by the Nephites Zarahemla. (Ether 9:31)

A careful reading of this verse may cause questions to arise. Neither

serpents nor flocks behave in the manner described here. That is,

poisonous serpents do not pursue animals; they defend themselves

against intruders including animals. Additionally, if in reality the

flocks represent sheep or cattle, it is contrary to the way these

animals react. They simply do not travel hundreds of miles just to get

away from snakes. . . .

If the serpents and flocks represent groups of people instead of

animals, the scripture in Ether 9:31 takes on an entirely different

meaning. The poisonous serpents may be symbolic of the secret

combinations, which did "poison many people" (Ether 9:31). This is

exactly how secret combinations work. They spread their deadly poison

among the people. They draw them away by false promises for the sole

purpose of obtaining power over the masses and to get gain. Hence, the

flocks could represent a righteous group of people who retreated to the

Land Southward to escape the wickedness that had come upon the land.

The word "flocks" is used in many instances in the scriptures to

represent a righteous group of people. Indeed, the Savior is the Good

Shepherd who watches over His flocks (Alma 5:59�60). (Allen, p. 25)

The logic in this exposition defies analysis but is typical of

assertions in Allen's book. He is basically making the claim that if

things don't mean what they appear to mean, their meaning is different.

There is no indication in the text that this verse should be read

metaphorically to refer to secret combinations. Allen extends the

simple claim that there was an infestation of snakes in the narrow neck

to mean that the snakes chased the animals over a hundred miles into

the land southward. The long distance is necessitated by his geography

correlation rather than the text, which simply states that flocks

"began to flee before the poisonous serpents" toward the land

southward. If a literal interpretation does not work in Allen's scheme,

perhaps the problem lies with his scheme and not with the Book of

Mormon account. Since people and their "flocks" are mentioned in this

same verse, "flocks" cannot refer to people. The description here is

evocative rather than necessarily ecologically precise. I don't imagine

the prophet who recorded this account was actually in the field moving

to and fro in the serpent patch to record specific reactions of man and

beast and tagging the serpents to see how far they traveled during the

year.

9.City of Desolation. This is actually a secondary criterion and relies

on the prior identification of the narrow neck to derive its

identification. The placement of this city and others around the narrow

neck is not precise. Our expectation is that ancient sites near the

neck should date to late Jaredite and Nephite times. Sorenson's

proposal certainly works here, as Warr acknowledges. For the Rivas

hypothesis, however, there are certainly sites of Nephite age, but it

is not clear that there are large sites (that would qualify as cities)

in the right area, or any of Jaredite age. For the moment, Sorenson's

proposal has the edge here.

10.City of Lib (same comments as for 9).

11.Easy to fortify. Warr's claim here goes beyond the text. The Book of

Mormon describes a fortified line in the narrow neck. Whether it was

easy or difficult to fortify is not stated, only that it was done and

therefore was possible and useful to do. On general principles, neither

model has an advantage here. Warr phrases things so he can deal with

environmental possibilism rather than archaeology. He would have

readers believe they should look to the ease of fortifying a particular

stretch of ground, with the implication being that the shorter distance

would be easier to handle. I have no quarrel with a shorter distance

being easier to defend than a longer one, all other things being equal.

But the Book of Mormon makes no such claim. Warr's claim is just a

guess passed off as textual inference. What would be more significant

would be to find defensible sites along a line in the area thought to

be the narrow neck. I know of none for either proposal, but neither

area has been investigated comprehensively by archaeologists.

Identified sites should date to the middle and late Nephite times. More

archaeology will have to be done in the two areas proposed before we

can judge this criterion for either proposal.

12.Jaredites, Olmecs, and occupation in the land southward. I have long

considered this a possible weakness of the Sorenson model. Many "ifs"

are in play with this criterion, however, and it involves a reversal of

previous logic that relies on locating the narrow neck to identify

correctly the lands northward and southward. Reversing the logic

requires one first to identify the land northward and then use this

knowledge to home in on the narrow neck. As many Latter-day Saint

authors have argued, the Olmecs are the best candidates for Jaredites.

If one assumes that the Olmecs were Jaredites, as Warr does, and if one

further assumes that the Jaredites stayed in the land northward and

only ventured into the land southward for hunting trips, as the text

implies, then the land southward would have to be south of known Olmec

occupations. Because Olmecs lived on both sides of the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec, all the way to El Salvador, it follows that Tehuantepec

cannot be the narrow neck of land. I give Warr's proposal the edge on

this criterion, as he has set it up. I consider this a serious

criticism that needs to be addressed, but it rides on many "ifs." When

real-world expectations do not accord with textual expectations, we can

derive one of several conclusions: first, that we have focused on the

wrong region or, second, that we may be interpreting the text

incorrectly.16 I expect to see some movement on Warr's criticism in the

future.

I will make two observations for the record to move this issue forward.

First, Sorenson avoids the blanket equation of Jaredites with Olmecs.

Rather, he argues that some Olmecs may have been Jaredites, but not all

of them.17 This means that Warr's assumptions do not apply to

Sorenson's model as framed. There remains the observation that the land

southward was blocked off for a time and at a later time became a

hunting reserve. Given what little is known of Jaredite settlement, we

need to be careful not to imagine that we know more than we do. Second,

the text states that the land southward was opened up during the days

of King Lib. It is worth pointing out that the explosion of Olmec

influence east of Tehuantepec (Sorenson's land southward) occurred

after 900 BC, with only spotty influence before. I think the text can

be read as indicating that the south lands opened up at this time, with

colonization being part of the package. Sorenson dates King Lib to

about 1500 BC,18 so Olmec/Jaredite occupation south of the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec after this time is not a problem for his model, contrary to

Warr's critique.

The criterion of settlement history involves extremely slippery issues

about other peoples, the nature of the Book of Mormon narrative, and so

on. In discussions of Nephite demography (see following section), it is

now commonplace to make the observation that Lehites and Mulekites were

not alone on the continent. The same was true for the Jaredites. Thus,

for Sorenson there is no necessary one-to-one correspondence between

Jaredites and Olmecs. Some Olmecs may have been Jaredites, others may

not. Claims in the Book of Mormon that Jaredites did not occupy a land,

therefore, are not equivalent to claiming that the lands were

unoccupied. All parts of North, South, and Middle America have been

occupied since at least 3000 BC. Presumably non-Jaredites occupied most

of these places for millennia, including the land southward, before

Jaredites ever got there. So, as with all Nephite/Lamanite questions,

one must sort out time, place, and culture in making an archaeological

identification of Jaredites.

It is worth noticing that Book of Mormon geographies positing

restricted lands and the presence of different peoples on American soil

ignore the killing flood of Noah's day. Some authors appear not to

realize the implications of their claims. Allen, for example, seems

unaware that some of his proposals rest on the proposition that Noah's

flood was not universal (in a literal, physical sense), and others on

the proposition that it was. He writes about the Jaredites as if they

came to empty land after the flood, as in the traditional view of Book

of Mormon geography, and he discusses the Nephites as if the flood

never happened and that Book of Mormon lands were full of strangers. He

cannot have it both ways.

Summary Evaluation of Proposed Necks

In preceding comments I dismissed three proposals for a Middle America

narrow neck without much discussion (namely, a partially submerged

Tehuantepec, the Yucatan Peninsula, and any slice of Panama in a

hemispheric view of Book of Mormon geography) and have evaluated

seriously only Sorenson's proposal for Tehuantepec and Warr's for the

Rivas peninsula. Of the twelve criteria listed by Warr for the narrow

neck, four were too ambiguous to help in distinguishing between the

Rivas and Tehuantepec proposals, and three others worked equally well

for both. Of the five remaining criteria, I gave Sorenson's proposal

the nod on four (seas, size of the neck, and the cities of Desolation

and Lib) and Warr's proposal a possible advantage on the remaining

question of Jaredite occupation of the land southward. As noted, this

is not an issue in Sorenson's model because he does not strictly

identify the Jaredites with cultures that archaeologists currently

consider Olmecs.19

One additional test is available. The narrow neck of land relates to

the overall configuration and scale of Book of Mormon lands. The text

makes claims for their occupation by various peoples at different times

and even provides some clues about total population. Therefore, the

plausibility of different candidates for the narrow neck of land can be

roughly assessed by looking at comparative demographic histories for

the different sectors, a claim implicit in Warr's last criterion about

the Jaredites and Olmecs.

Book of Mormon Peoples, Populations, and Lands

Why is knowledge of population size in the Book of Mormon important?

First of all, such knowledge would give us clues relating to the

geography of the Book of Mormon and enable us to infer the size of the

Nephite homeland; a large population would be necessary to inhabit a

continent, while a smaller population would be sufficient to fill a

more compact area such as Mesoamerica (or Costa Rica, which I have

proposed for the land southward). Second, knowledge of population size

would allow a better comparison between the Nephite and Jaredite

cultures. Third, awareness of population sizes would allow more

accurate projections of anticipated archaeological sites and ruins and

permit a more precise focus on their possible locations. Fourth, such

knowledge would permit inferences on possible inclusions of outside

groups into Book of Mormon populations. (Warr, "Book of Mormon

Populations," with minor editorial changes)

As noted above, Warr relied on this first use of population size to

dismiss Yucatan as the land northward because, in addition to its

230-mile wide neck, the land is not big enough, in his opinion, to have

housed the Jaredites in their heyday. Admittedly, relying on population

estimates as surrogate measures of territory is a crude method, but

useful nonetheless. In this section I explore its potential further,

after first providing a minimal case for population sizes of Book of

Mormon peoples.

Warr summarizes some of the basic discussion of Book of Mormon

population size published in other sources.20 The best information

comes from the battles of extermination. Nephite deaths at Cumorah

totaled at least 230,000; it is not clear whether this number included

all Nephites or only soldiers (see Mormon 6:10–15) or that units were

at full capacity. 21 I favor the view that it is a comprehensive tally,

but to be on the safe side, if only soldiers were counted and units

were at full capacity, the total Nephite population would have been

about one million, with the Lamanite population being considerably

greater than this, at least double the Nephites in the field and more,

counting the homeland.22 For the earlier Jaredite tragedy, the death

estimate comes in at conveniently rounded numbers of two million men,

women, and children for Coriantumr's people. Supposedly, the people of

Shiz would have constituted a population of comparable size. Counting

both factions, or peoples, gives an overall estimated population of

about four million.

Warr calculates maximum Jaredite population at forty to eighty million,

an estimate exaggerated by at least one order of magnitude, and then

some. He derives this estimate by assuming that the two million deaths

reported by the prophet Ether (see Ether 15:2) were only 10 to 20

percent of the male population. "This would result in a total male

population of 10 to 20 million. Multiplying this by an average family

size of 4 would give us a total population of 40 to 80 million" (Warr,

"Book of Mormon Populations").23 Warr's estimate generously exceeds any

information in the text. Ether's repetitious description notes that

"there had been slain two millions of mighty men, and also their wives

and their children" (Ether 15:2). Earlier in the same verse they are

described as "nearly two millions of his [Coriantumr's] people." It is

clear that women and children were armed and part of the conflict

(Ether 14:31; 15:15), and I suspect they are represented in the same

global statistic. The text's ambiguity allows room to push the death

estimate to eight million or to confine it to two million; in the

following speculations, I go with an estimate of four million Jaredite

dead in the final years of battle. In sum, my working estimates for the

final battles are about one million Nephites and more than twice as

many Lamanites. The Jaredite total is on par with the combined total of

Nephites and Lamanites. These estimates are portrayed in figure 8 as

proportioned squares. The area of each square represents relative

population and, by extension, territory size.

The squares show orders of magnitude rather than fine distinctions. The

proposition that population reflects territory size assumes that people

had to eat to live, that they had comparable dietary requirements, and

that most of their food came from cultivated crops, principally grains.

If one presumes similar population densities in an agrarian setting,

then population becomes a direct measure of the land under cultivation

and, thus, territory size. In checking these predicted relationships in

a real world setting, however, the actual size of different lands

should be expected to have varied according to local conditions of

terrain, cultivable ground, rainfall, and so on. Based on the

population boxes, my expectation is that Jaredite lands (basically the

land northward) were comparable in size to Nephite-Lamanite lands in

about AD 300 (basically the land southward). The land southward was

divided into two sectors by a narrow wilderness strip, with the land of

Zarahemla located northward of this wilderness and the land of Nephi to

the south. In terms of exercises with maps, my expectation is that the

land of Zarahemla was about a half or a third the size of the land of

Nephi. Figure 9 displays these relationships schematically. It is

important to remember that the land of Bountiful was a part of the

greater land of Zarahemla and that the land of Desolation was in the

land northward; the narrow neck divided Bountiful from Desolation. As

evident in figure 9, the land northward and the land of Nephi,

southward, were open-ended, so they could have accommodated more

population by extending boundaries. The land of Zarahemla, on the other

hand, was bounded on the east and west by seas, on its northerly margin

by the narrow neck, and on its southerly edge by the narrow strip of

wilderness. Because it was completely bounded and has the most precise

population statistics, it is the most useful datum for assessing the

validity of speculated geographies. In evaluating various proposals,

one should look for a land of Zarahemla that could have supported (and

did) about a million inhabitants in the fourth century AD and that had

simple agriculture.24

All geographies proposed in the past have fussed over the configuration

of lands and the distances between cities and geographic features, but

they have not been as concerned with territory sizes and the lands'

capacity to support human populations. Warr's analysis brings this

issue to the fore. As argued above, I estimate the ratio of maximum

populations, and thus of occupied territories, as roughly 4:3:1

(Jaredite:Lamanite:Nephite). How do the different Book of Mormon

geographies proposed for Middle America compare to these estimates?

Before attempting to answer this question, it will be useful to add two

more provisos to the mix. If population densities were equal for all

Book of Mormon peoples, one could use population as a direct measure.

But population density in the real world would have related to the

quality of cultivable land and not just simple acreage. No one would

expect the average population densities of Nevada or Alaska to match

those for Iowa or Indiana, for example. As a rough estimator of land

quality for each part of Middle America, I take as a ballpark measure

their populations at 1850, the era before the advent of mechanized

agriculture and industrialization, but three centuries after the

Spanish conquest and the demographic collapse this brought in its wake

(table 1).25

Table 1. Estimated populations, territory sizes, and population densities of Central American countries ca. 1850.

Country 1850 Population Km2 People/Km2

Belize

26,000

22,965

1.132

Guatemala

835,000

108,889 7.668

Honduras

308,000

112,090 2.748

El Salvador 520,000*

21,393

24.307

Nicaragua

335,000

130,000 2.577

Costa Rica

115,000

51,500 2.233

Panama

138,100

75,517 1.829

*The population in El Salvador for 1845 is listed at 480,000 and at 600,000 for 1855. I estimate 520,000 for 1850.

The other proviso is the assumption that archaeology can identify

different ancient groups and find evidence of the kinds and intensities

of interactions among them. The division of lands proposed by different

Book of Mormon geographers ought to correspond to archaeological

differences. For instance, Allen proposes a different mountainous

sector of Guatemala for his narrow strip of wilderness than does

Sorenson (compare figs. 10A and 10B). How do these rival proposals

stack up with the archaeology? Sorenson's division accords with

predicted archaeological differences, and Allen's does not.

Sorenson's Tehuantepec Model

This model does not need further commentary. It complies with the

simple requirements of relative territorial sizes remarkably well. The

reason Sorenson's model has become the industry standard is because it

constitutes a strong correlation between Book of Mormon requirements

and real world geography, anthropology, and archaeology.

Allen's Tehuantepec Model

Allen's model makes some of the same identifications as Sorenson's,

such as the narrow neck at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, but things

quickly diverge from there because Allen wants to preserve his Utah

sense of direction. I have pointed out that his proposed east sea

borders the Belize coast rather than the narrow neck. In his attempt to

follow directions, Allen distinguishes between a land northward—the

same as that identified by Sorenson—and a separate land north. The

Yucatan Peninsula directly north of the land of Zarahemla is considered

to be the land of Bountiful and, thus, part of the land southward.

Allen pins his interpretation on one ambiguous scripture that may

indicate a difference between the lands northward and southward with

the lands north and south.26 According to 3 Nephi 6:2: "And they did

all return to their own lands and their possessions, both on the north

and on the south, both on the land northward and on the land

southward." This verse does distinguish lands from directions but does

not mention the north lands. The few verses that mention north lands

refer to Jaredite lands, so the land north is used for the most part in

the same manner as the land northward. Allen's case for a different

land north from a land northward is extremely weak. Sorenson suggests a

more subtle difference:

"North country" and "north countries" seem to me from the contexts to

be applied only to the inhabited lowland portions of the land northward

that were reached from "the south countries" overland via the narrow

pass. But neither "north countries" nor "north country" is used in

regard to the colonies along the west sea coast, which are described

strictly as being in the "land northward."27

In Allen's model, the land of Bountiful is more important and larger

than the land of Zarahemla. I see no support in the Book of Mormon for

this proposition. Figure 10B shows a simplification of the Allen model.

Of greatest interest here is that Allen inverts the specified relations

among territories, with Nephite territories being four to five times

more extensive than Lamanite lands. Allen's Nephite territories are on

a par with those of the Jaredites in the land northward. This

constitutes a fundamental flub and sufficient reason for rejecting his

model outright. Other fatal flaws could be listed, but the few

mentioned suffice to disqualify Allen's model as a credible correlation

of Book of Mormon lands.

Allen's and Sorenson's models represent the two principal competitors

for a limited Mesoamerican geography centered at the Isthmus of

Tehuantepec. The remaining candidates for the narrow neck of land are

located in Central America. Starting with Guatemala, Central America is

shaped like a long, narrowing funnel that pinches together at the

juncture between Panama and Colombia, the place once thought to be the

narrow neck linking the northern and southern hemispheres in the

traditional view of Book of Mormon geography. This fact of physical

geography means that proposed necks and lands necessarily decrease in

size as one moves south toward Panama. The past several decades of

scholarship have demonstrated conclusively that a hemispheric model

contradicts Book of Mormon claims,28 so this original candidate for the

narrow neck in Panama has long since gone to its eternal rest. If one

excludes South America from consideration as a viable land southward,

as one ought, then another consequence of moving the narrow neck and

Book of Mormon lands southward in Central America is that the potential

size of the land southward also shrinks, and the requirements for land

sizes, or scale, become increasingly difficult to fulfill.

B. Keith Christensen's Guatemala Model

In a copyrighted but unpublished manuscript, B. Keith Christensen looks

to geology (plate tectonics and vulcanism) to sort the puzzle of Book

of Mormon geography. He proposes a narrow neck 150 to 225 miles wide

that crossed eastern Guatemala in two places as shown in figures 6 and

10C. I have already cited him to the effect that the narrow neck was

probably not so narrow and that the distance may have been traversed on

a horse.29 Christensen actually proposes two distances across this

narrow region—one line is a day and a half's journey long, and another

is a day's journey. The shorter distance is comparable to the

as-a-crow-flies distance across Tehuantepec, so Christensen cannot be

faulted for proposing an unreasonable distance for his narrow neck.

What is not apparent on maps, however, is that the terrain across

eastern Guatemala is difficult, so it would have taken many more days

to traverse than a comparable distance in Tehuantepec. I believe

Christensen has identified the most viable candidate in Central America

for the narrow neck, but in terms of travel time, it is over twice the

distance of Tehuantepec. How does it fare with Warr's land test?

Christensen's proposed Book of Mormon lands are shown in figure 10C.

His lands of Bountiful, Zarahemla, and Nephi are small. He proposes

that the limited land of Zarahemla was the Ulua River Valley of

Honduras. He does not discuss Nephi or the greater land of Nephi in his

text, but he appears to confine it largely to El Salvador. His greater

land of Zarahemla is comparable to or slightly larger than his land of

Nephi. On the other hand, his land northward is enormous, including

Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Nonetheless, these disparities may be

viable in terms of relative populations. As table 1 shows, El

Salvador's population density is at least triple that of any other

Central American country. If El Salvador was the location of the land

of Nephi, it is possible that the disparate numbers of Lamanites

compared to Nephites related to their superior and larger tracts of

agricultural land. Even so, the lands appear too small. Christensen's

land of Zarahemla takes in less than a third of Honduras, so the total

1850 population of this place would have been less than 200,000 people,

close to the absolute minimum estimate for the number of Nephites

killed at Cumorah. In sum, using the 1850 census as a close estimate of

pre-Columbian population provides a possible correlation with the Book

of Mormon account, but only if the slaughter at Cumorah was a quarter

of a million Nephites rather than a million. Given the funnel shape of

Central America, it is unlikely that any proposed geographies to the

south of Guatemala and El Salvador would qualify.

James Warr's Rivas Model

I have already found Warr's model wanting on one criterion, the narrow

neck of land. The model is also deficient in terms of scale. His

quotation introducing this section indicates that Costa Rica is his

candidate for the land southward. In his model, half of Costa Rica

comprised the former lands of Zarahemla and Bountiful, or greater

Zarahemla, and the other half was the land of Nephi. This bifurcation

yields two small, equal-sized lands. To meet the population

expectations of the Book of Mormon account, he can always toss in

Panama as a southern extension of the land of Nephi, but even adding

all of Panama's population does not resolve his population problem. The

rough population estimates in table 1 list the total population of

Costa Rica in 1850 as 115,000. I will not argue the archaeological

merits of this number, but I think it is a reasonable estimator of

pre-Columbian populations 1,700 years ago. In Warr's model, half this

population would have been Nephites and the other half Lamanites,

yielding a total estimated Nephite population of less than 60,000. This

figure can't even account for the absolute minimum Nephite population

of 230,000 dead at Cumorah in AD 387, and it creates even greater

problems for the Book of Mormon narrative and the requirement that

Lamanites significantly outnumber Nephites. Recall that Warr estimates

the total population of Nephites and Lamanites at eight million.30 This

estimate exacerbates his problem because it is four times the total

population of all of Central America in 1850.

Warr does not consider the situation as dire as I do, of course, or he

would not have advanced his model and method. He provides the following

summary of his population expectations:

To get some idea of comparable modern populations on the proposed land

mass, let us look at current and pre-conquest populations of Central

America. Nicaragua had an estimated pre-conquest Indian population of

600,000. Panama's pre-conquest population was estimated at 200,000.

Modern populations are as follows: Mexico, 105 million; Guatemala, 14

million; Honduras, 7 million; El Salvador, 6.5 million; and Nicaragua,

5 million. These combined countries would form my proposed Jaredite

land northward with a total combined population of 137.5 million.

Modern populations in Costa Rica and Panama are respectively 4 million

and 3 million for a combined total of 7 million for my proposed

Nephite/Lamanite area. So it appears that the populations I have

suggested for the Nephites and Jaredites could easily fit into the

proposed areas with plenty of room to spare. On the other hand, the

projected population would not have been sufficiently large to

reasonably settle substantial portions of the North or South America

land masses. (Warr, "Book of Mormon Populations")

This argument is patently fallacious and internally self-defeating.

Warr marshals population figures that meet his estimates for 80 million

Jaredites and 8 million Nephites/Lamanites. He does so by projecting

modern populations back in time and ignoring technological change and

modern medicine. This is akin to estimating the pre-Mormon population

of Utah at several million Utes because that is how many people reside

in Utah today. Obviously, several factors in the last several centuries

have encouraged unprecedented population growth and density, and these

same factors have led to the high populations in Mexico and Central

America.

The more important figures Warr provides are those for preconquest

populations. Nicaragua's preconquest population was 12 percent of its

modern population, and Panama's preconquest population was 6.7 percent.

By adjusting modern populations to this preconquest standard, the

central error of Warr's argument stands revealed. Taking 9 percent as a

useful constant, the total population for Warr's land northward would

be this fraction of 137.5 million, or 12,375,000 people.31 This is more

than enough to comply with the Jaredite requirement. Taking the

preconquest data available for Panama and adding an estimate for Costa

Rica of 360,000 people (9 percent of 4 million), yields a total of

560,000 people, with the estimate for the Nephite portion being 180,000

people. This approximates the 230,000 minimum but not the 2 million

estimated and expected by Warr. His model fails by his own criteria and

method. His proposed Book of Mormon lands are several sizes too small.

A Panama Model

I have become aware of a limited Panama model proposed by Patrick L.

Simiskey that identifies a narrow neck in the middle of Panama (see

fig. 1 no. 5).32 Because his work is still in progress and unpublished,

it is not appropriate that I comment on its details. For purposes of my

consideration of Middle American candidates for narrow necks, it

suffices to judge Simiskey's proposal solely in terms of population and

territory size. The land southward in his model is that between the

narrow neck in the middle of the country and the narrow neck bordering

Colombia at its southern extremity. The greater land of Zarahemla is

roughly half this land southward, or one fourth of Panama, with the

land of Nephi being the same size. The 1850 population of Panama was

less than 140,000 (table 1), so by my crude calculations, the estimated

Nephite and Lamanite populations would have each been about 35,000. As

cited, Warr lists a preconquest population of Panama of 200,000 (a

suspiciously round number), a fourth of which would give an estimated

total Nephite population of 50,000—still far short of the casualty list

of Cumorah. If these estimates are anywhere close to fourth-century AD

populations, this limited Panama model is off by one order of

magnitude, and then some.

Summary of Evaluations of Scale

The preceding evaluations are based on the simple proposition that

total population relates directly to the extent of productive land. I

have not attempted to finesse any of the information or to introduce

qualifying variables. Comparing the relative size of various proposed

Book of Mormon lands to nineteenth-century census data provided a rough

measure for evaluating five models. Sorenson's limited Mesoamerican

model preserves the population ratios claimed in the Book of Mormon and

can account for the absolute totals. Allen's Tehuantepec model does not

because his Nephite lands are much bigger than those for the Lamanites.

I did not point out the known archaeological fact that the lands he

designates as Nephite enjoyed higher population densities during the

critical fourth century AD, so the disparity in territory sizes

indicated in figure 10B would actually have been much greater when

considered as population sizes. If Allen's identification of Nephite

lands is accurate, then the Lamanites were always attacking vastly

superior forces, something flatly contradicted in the text.

Of the three proposals for Book of Mormon lands in Central

America—Warr's, Christensen's, and Simiskey's—only Christensen's comes

close to matching the requirements in the text, and then only barely.

It has other serious problems besides its low populations, however,

such as an improbable narrow neck of land. His model merits future

consideration but, for the moment, is not a serious rival to

Sorenson's. Candidates for Book of Mormon lands in Costa Rica and

Panama are not credible because they fall far short of required

population—in terms of absolute numbers as well as relative numbers.

The archaeological and cultural details do not fit either. The bottom

line of my quick analysis is that Sorenson's model is the only credible

one in terms of physical geography and archaeology. These are not the

only criteria that ought to be considered, however. Allen stresses in

his work that multiple lines of evidence, or independent witnesses,

should be considered in identifying Book of Mormon lands, a point with

which I agree and to which I now turn.

Matters of Book of Mormon Culture

Allen follows M. Wells Jakeman's approach to Book of Mormon or sacred

geography in pursuing a combination of archaeology, ethnohistory, and

anthropology, an approach he calls the law of witnesses. "This simply

means that if we make a Book of Mormon geographical hypothesis, we

ought to test that hypothesis against the archaeological, cultural, and

traditional history of the area. In the absence of these two or three

witnesses, I feel we stand on rather shaky ground."33

Part of the frustration of Sacred Sites is that Allen jumps all over

the place supplying tidbits from each "witness" without wrapping up

their testimony in a coherent fashion, or more important, without

demonstrating the validity of his claims or questions. He does not

evaluate sources critically (there is no cross-examination in his

court). The desirability of multiple lines of evidence and witnesses is

beyond question, but it loses much in Allen's application. He raises

some good points, most taken from other authors. For example, he points

out that Mesoamerica is the only area of the Americas where people

could read and write, an absolutely fundamental requirement for Book of

Mormon peoples. The Costa Rica and Panama models fail this simple test.

As before, the industry high standard has been established by John

Sorenson. He provides excellent discussions of Book of Mormon cultural

details in various books, with the most accessible being his Images of

Ancient America.34 This book is a comprehensive introduction to

Mesoamerican culture, with superb and carefully chosen color

illustrations. When I first saw Allen's Sacred Sites and its over 100

color illustrations I thought he was trying to emulate Sorenson's book,

but there is no comparison in the quality of the illustrations or the

arguments. Sorenson's Images of Ancient America has raised the stakes

in publishing, with the most obvious effect being the trend to color

illustration. Sorenson's book was followed by Jerry Ainsworth's

generously illustrated but substantially flawed The Lives and Travels

of Mormon and Moroni and then by Joseph Allen's Sacred Sites. Covenant

Communications also has a companion picture book on the market similar

to Sacred Sites: S. Michael Wilcox's Land of Promise: Images of Book of

Mormon Lands.35 In comparison with Allen's book, the photographs and

illustrations in Land of Promise are significantly better. Wilcox is

committed to Mesoamerica as the location of Book of Mormon lands, but,

unlike Allen and Sorenson, he does not appear to be committed to any

particular correlation. Similar to Allen's book, Land of Promise uses

images of Mesoamerican archaeology and cultures as a platform for

sermonizing rather than explaining details of the Book of Mormon, and

the book's content is inferior to its graphics. Of Covenant's two

contributions, Land of Promise is the superior product.

In the course of writing this essay, I have read parts of Allen's books

dozens of times and have derived a simple rule of thumb: To the degree

that Allen cribs from Sorenson, his arguments are sound; to the degree

he does not, caveat lector (let the reader beware). When he proposes

novel arguments, Allen invites trouble. Space permits consideration of

only one spot of trouble per witness.

Archaeology: The Lehi Tree of Life Stone

Allen continues to follow Jakeman in considering Stela 5 (aka the Lehi

Stone) at Izapa, Mexico, as one of the most convincing pieces of

archaeological evidence for the authenticity and truth of the Book of

Mormon, so much so that this stone received pride of place on the cover

of Sacred Sites. It is telling that all the details are blurred and

presented in false color; details don't seem to matter in Allen's

presentations. But any serious argument about the meaning of carved

images needs to deal with crisp data. All the monuments Allen had

redrawn to grace his publication were transformed from sharp line

drawings to blurred globs of color, clearly a move in the wrong

direction. I recently presented a new and better drawing of the details

of Izapa Stela 5 and what I consider strong arguments, based partly on

this drawing, for why it does not deserve reverence from Allen or his

Mormon tour groups.36

The only convincing parallel between the scene on the monument and

Lehi's dream (as recorded in the Book of Mormon) is the presence of a

fruit tree and water. This falls several miles short of a strong case

for correlation. The scene, its arrangement, and style are purely

Mesoamerican and derive from themes prevalent among earlier cultures

dating back before Lehi was born. Allen is aware of my arguments but

dismisses them summarily by soliciting other opinions (from Bruce

Warren and Richard Hauck, archaeologists, but not qualified experts)

that claim the correspondences are there. The argument should not hinge

on expert testimony—mine, Allen's, Warren's, or that of others. Rather,

it should be a matter of accepted facts and their ramifications. For

the moment, Allen's arguments constitute a fallacious appeal to

authority.

In his book, Allen provides another twist to his argument for Old World

(aka Book of Mormon) connections to the stone. He proposes that the

scene on Stela 5 is laid out as a visual chiasm. In an earlier chapter,

he presents a visual analysis of a carved panel from the Classic Maya

site of Palenque, Chiapas, to show its chiastic structure. This

argument is absurd and self-defeating. What Allen has identified is not

chiasms but mirror imagery and the bilateral symmetry of some

sculptures, a feature common to art the world over and therefore of no

particular analytical merit by itself. As is typical with most of his

arguments, Allen does not pursue the obvious implications of his own

assertions. For example, if the representations on Stela 5 were indeed

pure mirror symmetry, then the seated woman on the lower left of the

panel (aka "Sariah" seated behind "Lehi") would have a female

counterpart on the far right of the panel (i.e., the figure behind

"Nephi"). There is a figure, holding a parasol, in this position that

Jakeman identified as "Sam." This figure is eroded but does appear to

represent a female. So the symmetry of Stela 5 is indeed impressive,

but it eliminates "Sam" from Lehi's family gathering. Of greater

difficulty, the new drawing has identified additional human figures on

the stone not accounted for in Jakeman's/Allen's account. Their

interpretation flounders in light of new details. Stela 5 portrays

Mesoamerican kings worshipping their gods and conducting sacred

ceremonies—and not Lehi's dream. It is interesting that a world tree or

tree of life is involved, but it does not constitute direct evidence of

the Book of Mormon. What it does demonstrate, however, is that other

Mesoamerican peoples living alongside the Nephites shared some of the

same metaphors and images as the Nephites. In other words, the Nephite

record is not out of place in this cultural setting.

Culture: Weights and Measures in the Guatemala Highlands

For years now Allen and his colleagues have been making much of the

small, nested brass weights used in Indian markets in highland

Guatemala because the graduated weights parallel the weight ratios

mentioned in Alma, chapter 11, for units of monetary exchange. Pictures

and explanations of these weights are now being published as verified

knowledge and as corresponding with the Book of Mormon.37