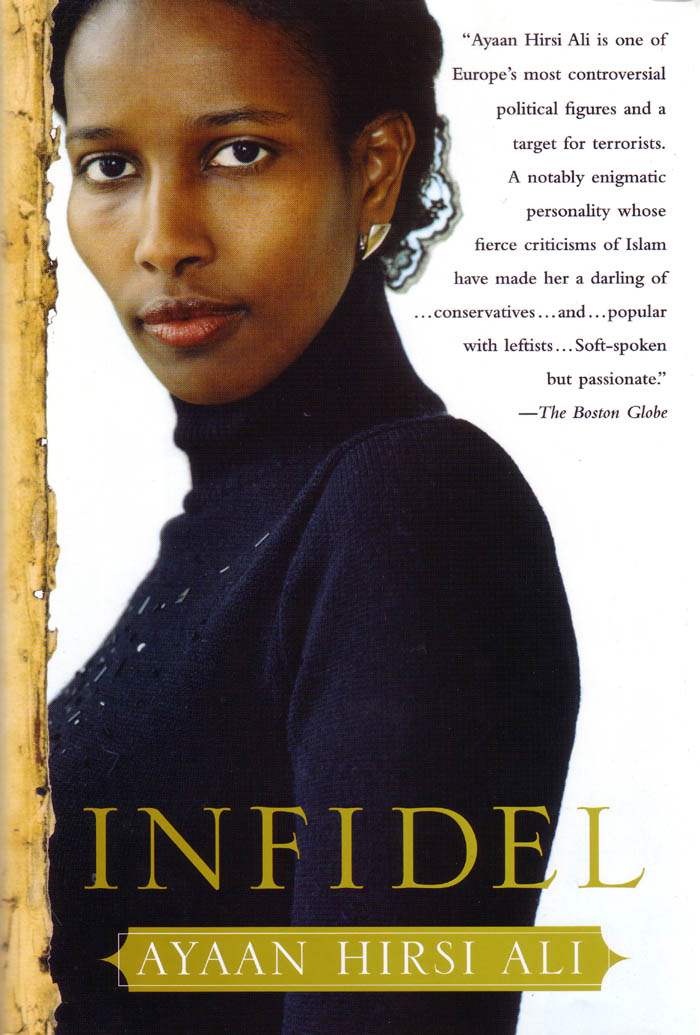

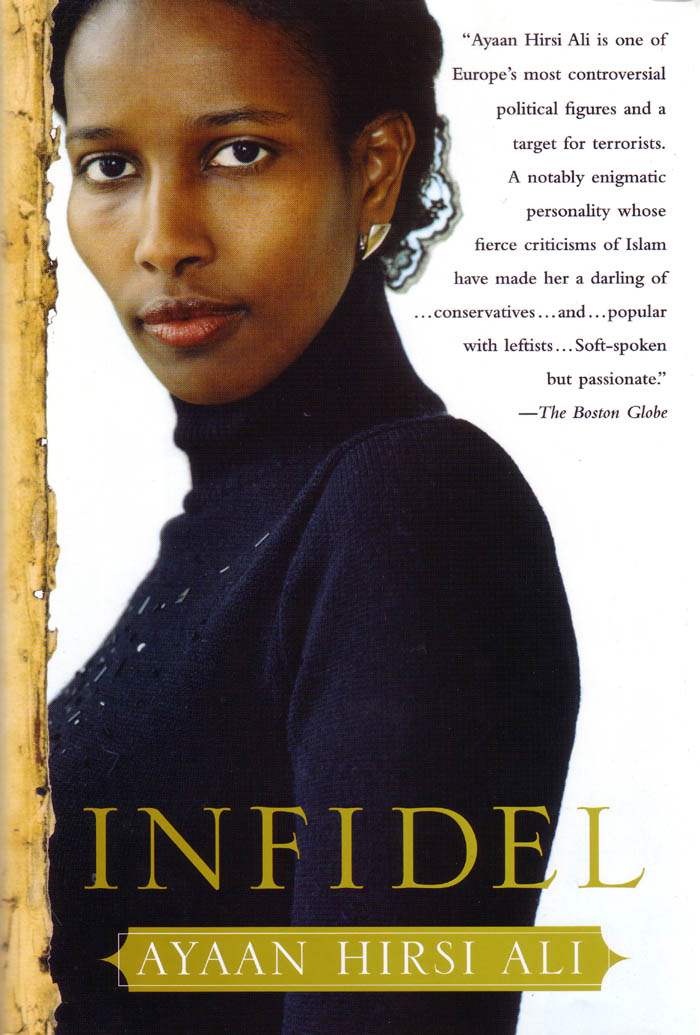

Infidel by Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Chapter 1: Bloodlines

Chapter 2: Under the Talal Tree

Chapter 3: Playing Tag in Allah's Palace

Chapter 4: Weeping Orphans and Widowed Wives

Chapter 5: Secret Rendezvous, Sex, and the Scent of Sukumawiki

Chapter 6: Doubt and Defiance

Chapter 7: Disillusion and Deceit

Chapter 8: Refugees

Chapter 9: Abeh

Chapter 10: Running Away

Chapter 11: A Trial by the Elders

Chapter 12: Haweya

Chapter 13: Leiden

Chapter 14: Leaving God

Chapter 15: Threats

Chapter 16: Politics

Chapter 17: The Murder of Theo

Epilogue: The Letter of the Law

Political writer Hirsi Ali discusses democracy and Islam

Tuesday, 5 August , 2008

Reporter: Mark Colvin

ABC.net.au

MARK COLVIN: The word "apostate" has fallen

into relative disuse in the West in the last couple of 100 years.

The idea that leaving your religion, apostasy, should be punished, has largely

died out since the Enlightenment.

But Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who's been in Australia over the last few days, is in

continuous fear for her life because she is an apostate from Islam.

In 2004, in the Netherlands, her friend, the filmmaker, Theo van Gogh, was

stabbed to death for an anti-Islam film for which she wrote the script. A death

threat against her was pinned to the corpse with a knife.

In her subsequent book, Infidel, she stepped up her attack on global Islam. And

in Australia she's been talking about the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali says the creed of Islam itself, rather than the way it's

practised, is the problem, because the ideas of Mohammed are incompatible with

the ideas of liberal democracy.

(To Ayaan Hirsi Ali) Is Islam the problem or is fundamentalist Islam the

problem?

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: Islam, as a creed, is the problem, depending on how you define

the problem and I define it as the ideas of Mohammed are incompatible with the

ideas that liberal secular democracies are based on.

And I also want to emphasise that it's not Muslims as in individuals, because

they're varied, they're very diverse. Some Muslims are a problem, some Muslims

are not, some Muslims are apathetic, but Islam as a system of ideas is

incompatible with liberal democracy as a system of ideas.

MARK COLVIN: And yet here in Australia we live next to an enormous, mainly

Islamic country, which is slowly moving towards democracy which would seem to

indicate that Islam itself is not necessarily a complete barrier to doing that.

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: Islam is a barrier to doing that, but your next door neighbour,

which is the world's probably largest Muslim country, started out after the

decolonisation process as a secular democratic country, and right now we see two

trends.

We see Indonesians who are evolving in their understanding and practice of

democracy, but we also see Indonesians who are affected by the Middle East, and

especially by the Islamic Radical Movement and who are choosing to introduce

Sharia, or parts of Sharia, into Indonesia, and I think it's that trend that

Australia should not ignore. And it's that trend that Indonesia itself should

not ignore.

MARK COLVIN: If you go back to say, the 17th century in Europe, Christianity,

both Protestant and Catholic Christianity, was essentially fundamentalist. And

if you looked at the religion then of Christianity, you would have said, "This

is a fundamentalist religion which can never evolve democratic states." Why is

Islam different?

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: Well, first of all, it's not Christianity that produced the

Enlightenment and all of that, there were perhaps Christians, but also

individuals in Europe, in the United States and elsewhere, who proposed ideas to

move away from religion and furnishing their lives and society by means of

religious ideas and moved on secular ideas.

Why is Islam different from Christianity? I think one main difference is the

separation of divine rule from secular rule. Islam does not allow it and I have

not yet see a Muslim movement saying we should now move away or separate the

two.

MARK COLVIN: But the point I'm making, I suppose, is that there was a time when

Christianity didn't allow it either. Is Islam permanently incapable of

reformation or change in that way?

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: It's very important to make a distinction between Islam as a

set of ideals, Christianity as a set of ideas and so on. And human beings,

individuals, Muslims, are capable of change. They're capable of forming their

religion, they're capable of thinking differently about different things.

Islam as creed as incapable of change in the sense that … for instance there's a

read-only lock on the Koran. Anyone who proposes to change anything in the Koran

is considered an apostate, and is immediately killed or threatened with death.

Muslims hold that the Prophet Mohammed is infallible. In fact, it's a claim he

did not make, but that is accorded to him. So that Muslims must in the 21st

century, emulate the example of the Prophet Mohammed. And I think Islam will

change, will be reformed, if a fair amount of Muslims abandon those dogmas.

MARK COLVIN: The Enlightenment, which you're here to talk about, only really

came about after a very long period, a couple of 100 years, of extreme violence

between Christian sects, notably the 30 years war, and the Peasant Wars, and so

forth.

Is it necessary for Islam to have to go through that kind of thing, or is there

a short cut?

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: Well, that depends on the people. If you have, as we have right

now, people who want to practice Islam in its most pure form, and impose it on

not just Muslims, but everyone else, then you're going to see a resistance both

from within Islam and outside of Islam.

And that resistance, if that doesn't lead to a dialogue, a peaceful dialogue

with a peaceful outcome, will lead to bloodshed. And if you look, if you listen

to the rhetoric of al-Qaeda and Bin Laden, these are people who say we can't

compromise unless everyone becomes a Muslim. Now, everyone is not going to

become a Muslim, and so then you set the stage for violence, and that violence

is then caused by the zealots, by the puritans.

If freedom of expression is limited as it is in Muslim countries, and as large

numbers of minorities in Western societies are demanding, then that means the

free exchange of ideas. And the stages for that diminish and people get

frustrated and that could lead to violence.

MARK COLVIN: When you say, "Large numbers of people in Western societies are

demanding", what are you referring to?

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: Everyone followed the cartoon crisis, or the crisis about the

cartoon drawings of Mohammed in Denmark. That led to an explosion of violence

because large groups of Muslims still will not accept criticism of their

religion.

Over and over again, when in the name of Islam, human blood is shed, Muslims are

very quiet. When drawings are made or some perceived slight or offences given by

writing a book, or making a drawing, or in some way criticising the dogmas of

Islam, people take to the streets. We have all these leaders of the organisation

of Islam, the countries who oppressed on people, coming to demand the people

apologise.

And I think it's this discrepancy that more and more people see as violence and

intolerance and the lack of freedom inherent in the creed of Islam.

MARK COLVIN: Finally, a personal question. You've paid an enormous price in

terms of your own personal security for saying what you say. What makes it worth

it?

AYAAN HIRSI ALI: Freedom and a vision that it is so much more important, so much

better to live in freedom than to be overtaken by a wave of fanatics who in the

name of Islam wants to impose their world view on us.

And I think the best thing to do is to resist and to take away from them, the

monopoly that they now have on the hearts and minds of Muslims.

MARK COLVIN: Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who's been in Australia talking about the ideas of

the Enlightenment as a guest of the Centre for Independent Studies.