MUSLIM HATE FOR DEMOCRACY

Ansar Beit al Magdis will fight 'crusaders, Zionists'

Why facade democracy will never work in Muslim countries

by Iqbal Siddiqui

(Tuesday October 18 2005)

"In recent centuries, ordinary people in Western countries have gradually been persuaded to adopt the political ideals and culture of liberal democracy, making them easy targets for elite manipulation using liberal democratic institutions and processes."

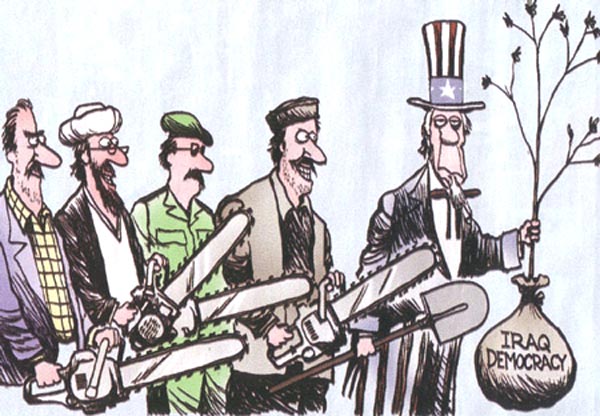

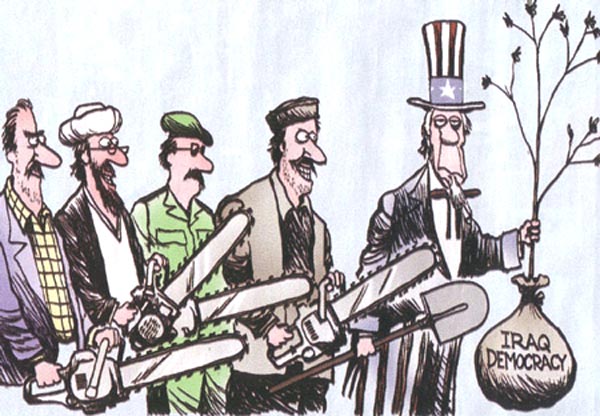

When Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak announced earlier this year that last month’s presidential elections would be the first ever to permit other candidates to stand directly against him, the announcement was greeted in the West as part of the “democratic dividend” of Bush’s invasion of Iraq. According to the American neo-conservative mythology, one of the reasons that Muslims are so anti-American is that they live under repressive dictators who blame the West for all that is wrong in the world. In keeping with this remarkable understanding of contemporary history, the US’s main object in invading Iraq was to restore freedom for the Iraqi people and make Iraq a beacon of democracy in the Muslim world, and an inspiration to other Muslim peoples around the world to embrace freedom, democracy and the altruistic American hegemon that can provide both. The logic was that the example of Iraq would prompt Muslim peoples to demand democracy, as people in the former Soviet bloc did in 1989, and force repressive Arab rulers to permit political reform as the only way of averting popular unrest.

During a visit to Cairo in June, shortly after the multi-candidate elections were announced, US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice sought to emphasise US claims to be championing democratic rights in the Arab world by publicly lecturing Mubarak on the need for further liberalisation. She pointed out that there were two essential prerequisites if the elections were to be internationally recognised as free and fair: that they should be monitored by international observers, and that Egypt’s repressive state of emergency laws should be repealed. Neither of these conditions was met; the elections were monitored only by state observers and the state of emergency remains in place, with the Ikhwan al-Muslimun (Islamic Brotherhood), long recognised as Egypt’s largest and most popular opposition group, remaining officially banned and therefore unable to run any candidate against Mubarak.

Despite this, and numerous other problems with the elections, which were widely recognised in the Arab world as nothing more than a political farce providing Mubarak with only the thinnest veneer of legitimacy, George W. Bush greeted the elections last month as a triumph for America’s foreign policy, saying during a speech in San Diego that “Across the broader Middle East, we can see freedom’s power to transform nations and deliver hope...” He compared the elections in Egypt to those “in Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon and the Palestinian territories... [where] people have gone to the polls and chosen their leaders in free elections. Their example is inspiring millions across that region to claim their liberty and they will have it.”

In fact, all we have seen in Egypt last month has been a repeat, albeit perhaps in a slightly refined form, of a political process widely recognised in the Arab world, that of “al-democratiyya al-shakliyya”, usually translated as facade democracy. This refers to the establishment of institutions and processes that have all the trappings of normal democratic politics without making any genuine difference to the established power structures in the country. Egypt has long been recognised at the classic example in the Arab world. It has several political parties, including the ruling National Democratic Party, regular elections to parliament and now a directly elected president (he was previously elected by parliament and then confirmed by referendum), although no-one believed for one moment that there was any prospect of him accepting defeat, shaking hands with his successor and quietly moving out of the presidential palace. In reality, no-one regards this apparatus as any real check on the power of the establishment; rather it serves not to make government accountable to the people, but as to secure and legitimise the position of the ruling NDP, the military elites that control it and the civilian elites that have decided to hitch their fortunes to its wagon. Instead of providing channels through which the Egyptian people can influence their government, these political institutions and processes provide only channels through which those in power can distribute patronage and manipulate the people they are supposed to lead.

This is the sort of democracy that the US is now promoting in other Arab countries, although the progress in places like Jordan and Saudi Arabia is too limited for Bush yet to count them among his success stories. And the Egyptian example demonstrates that no further loosening of the reins of power is intended there, despite Rice’s pious words. There was, notably, no objection to the fact from the Ikhwan, recognised as Egypt’s main opposition movement, is not permitted to operate freely or to contest the elections. As in the past, the establishment has used the system to manipulate its allies and supporters; it clearly intends to use it also to manipulate its opponents, by promoting some -- secular and nationalist groups -- over others, particularly Islamic ones, which might prove more of a genuine challenge to the powers that be, as FIS demonstrated in Algeria in the late 1980s: an example of political liberalisation under Western guidance getting out of hand. It may well be that Egypt, having pioneered the system of pro-Western facade democracy, is now regarded as stable and secure enough to allow further limited reforms without the risk of the process getting out of hand and actually permitting any genuine expression of the popular will, which would of course be Islamic and anti-American.

This is, of course, the key problem for the West. Although they speak of the democratic ideals of popular and accountable governments that reflect the values and wishes of their people, they know that the wishes of Muslim people are bound to oppose Western interests. They also know that the political elites in Muslim countries are not secure or powerful enough to manipulate open political systems to their ends, as the capitalist and corporate political elites can do in America and other Western countries. In Western countries, we see the limits of democratic freedoms whenever those in power feel threatened, for example by Muslim dissidence in America, Britain and European countries today. Faced with a genuine political challenge, such as the widespread opposition to their wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Western states exploit incidents such as the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington, and the bombings in London on July 7 this year, to enact illiberal and repressive legislation against “extremism” and “threats to national security” which actually target political opposition more than terrorist activities.

Although the West likes to boast of democracy as a Western gift to the world, reflecting the values and culture of the secular West, it actually owes more to technological advances of modernity, which enable more and more people to be informed about issues affecting their lives, particularly through improved means of communication, and more and more people to aspire to influence the forces that define their lives. This popular involvement and empowerment, which may take different forms, is the real essence of democratisation, rather than liberal ideals such as freedom or equality, or political institutions and processes such as parliament, parties and elections. This is why, in places such as Egypt now, as in the Soviet Union and East Germany during the communist period, and in Iraq under Saddam Hussain, it is possible to have “democratic” political institutions without any sign of genuine popular involvement or empowerment. And that also the situation that exists in western countries, albeit in more sophisticated form: a reality that is now being increasingly realised by Western people.

In recent centuries, ordinary people in Western countries have gradually been persuaded to adopt the political ideals and culture of liberal democracy, making them easy targets for elite manipulation using liberal democratic institutions and processes. The problem for the West is that the masses in Muslim countries have not accepted these political ideals and culture because they have a very strong and powerful indigenous alternative, the political ideals and culture of Islam. When Muslims talk of wanting democracy in their countries, they do not mean, a few westernised exceptions apart, that they want to import western-style secular liberalism, as the West likes to assume; they mean that they want freedom from oppression and repression so that they can establish political institutions reflecting their Islamic political culture and ideals, through which they can achieve independence from foreign hegemony, and popular participation, empowerment and accountability, on their own terms.

This is what the Muslims of Iran achieved through the Islamic Revolution in 1979, inspired by the leadership of Imam Khomeini. As has been said before, the Iranians were fortunate in that they caught the Western power unawares and were able to take control of their country, albeit only at immense sacrifice and cost. It is not a coincidence that, from then until now, Iran has the highest levels of popular participation and political empowerment of any Muslim country in the Middle East. Since then the West has been far more aware of the risk posed by Islamic movements and has done whatever it had to to neutralise them, from the sheer brutality of Algeria to the political manipulation of countries like Jordan and Egypt. Nonetheless, the political instincts of the Muslim ummah remain unchanged, and Muslims will only accept such forms of political reform as enable them to establish Islam in their societies.

That is why attempts by Mubarak and his like to establish democratic facades for their authoritarian regimes are bound to fail, as are attempts by the West to introduce secular and liberal understandings of democracy into Islamic and Muslim political discourse.

Mr. Iqbal Siddiqui, Editor of Crescent International and Research Fellow at the Institute of Islamic Contemporary Thought, is a regular contributor to Media Monitors Network (MMN)

A Year of Living Dangerously

Nov 4, 2005

Remember Theo van Gogh, and

shudder for the future.

BY FRANCIS FUKUYAMA

Watch Theo van Gogh's movie "Submission", click here (Windows Media Player)

One year ago today, the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh had his throat ritually

slit by Mohamed Bouyeri, a Muslim born in Holland who spoke fluent Dutch. This

event has totally transformed Dutch politics, leading to stepped-up police

controls that have now virtually shut off new immigration there.

Together with the July 7 bombings in London (also perpetrated by second

generation Muslims who were British citizens), this event should also change

dramatically our view of the nature of the threat from radical Islamism. We have

tended to see jihadist terrorism as something produced in dysfunctional parts of

the world, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan or the Middle East, and exported to

Western countries.

Protecting ourselves is a matter either of walling ourselves off, or, for the

Bush administration, going "over there" and trying to fix the problem at its

source by promoting democracy. There is good reason for thinking, however, that

a critical source of contemporary radical Islamism lies not in the Middle East,

but in Western Europe. In addition to Bouyeri and the London bombers, the March

11 Madrid bombers and ringleaders of the September 11 attacks such as Mohamed

Atta were radicalized in Europe. In the Netherlands, where upwards of 6% of the

population is Muslim, there is plenty of radicalism despite the fact that

Holland is both modern and democratic. And there exists no option for walling

the Netherlands off from this problem.

We profoundly misunderstand contemporary Islamist ideology when we see it as an

assertion of traditional Muslim values or culture. In a traditional Muslim

country, your religious identity is not a matter of choice; you receive it,

along with your social status, customs and habits, even your future marriage

partner, from your social environment. In such a society there is no confusion

as to who you are, since your identity is given to you and sanctioned by all of

the society's institutions, from the family to the mosque to the state. The same

is not true for a Muslim who lives as an immigrant in a suburb of Amsterdam or

Paris.

All of a sudden, your identity is up for grabs; you have seemingly infinite

choices in deciding how far you want to try to integrate into the surrounding,

non-Muslim society.

In his book "Globalized Islam" (2004), the French scholar Olivier Roy argues

persuasively that contemporary radicalism is precisely the product of the "deterritorialization"

of Islam, which strips Muslim identity of all of the social supports it receives

in a traditional Muslim society. The identity problem is particularly severe for

second- and third-generation children of immigrants. They grow up outside the

traditional culture of their parents, but unlike most newcomers to the United

States, few feel truly accepted by the surrounding society. Contemporary

Europeans downplay national identity in favor of an open, tolerant,

"post-national" Europeanness. But the Dutch, Germans, French and others all

retain a strong sense of their national identity, and, to differing degrees, it

is one that is not accessible to people coming from Turkey, Morocco or Pakistan.

Integration is further inhibited by the fact that rigid European labor laws have

made low-skill jobs hard to find for recent immigrants or their children. A

significant proportion of immigrants are on welfare, meaning that they do not

have the dignity of contributing through their labor to the surrounding society.

They and their children understand themselves as outsiders. It is in this

context that someone like Osama bin Laden appears, offering young converts a

universalistic, pure version of Islam that has been stripped of its local

saints, customs and traditions. Radical Islamism tells them exactly who they

are--respected members of a global Muslim umma to which they can belong despite

their lives in lands of unbelief. Religion is no longer supported, as in a true

Muslim society, through conformity to a host of external social customs and

observances; rather it is more a question of inward belief. Hence Mr. Roy's

comparison of modern Islamism to the Protestant Reformation, which similarly

turned religion inward and stripped it of its external rituals and social

supports. If this is in fact an accurate description of an important source of

radicalism, several conclusions follow. First, the challenge that Islamism

represents is not a strange and unfamiliar one.

Rapid transition to modernity has long spawned radicalization; we have seen the

exact same forms of alienation among those young people who in earlier

generations became anarchists, Bolsheviks, fascists or members of the Bader-Meinhof

gang. The ideology changes but the underlying psychology does not. Further,

radical Islamism is as much a product of modernization and globalization as it

is a religious phenomenon; it would not be nearly as intense if Muslims could

not travel, surf the Web, or become otherwise disconnected from their culture.

This means that "fixing" the Middle East by bringing modernization and democracy

to countries like Egypt and Saudi Arabia will not solve the terrorism problem,

but may in the short run make the problem worse.

Democracy and modernization in the Muslim world are desirable for their own

sake, but we will continue to have a big problem with terrorism in Europe

regardless of what happens there.

The real challenge for democracy lies in Europe, where the problem is an

internal one of integrating large numbers of angry young Muslims and doing so in

a way that does not provoke an even angrier backlash from right-wing populists.

Two things need to happen: First, countries like Holland and Britain need to

reverse the counterproductive multiculturalist policies that sheltered

radicalism, and crack down on extremists.

But second, they also need to reformulate their definitions of national identity

to be more accepting of people from non-Western backgrounds. The first has

already begun to happen. In recent months, both the Dutch and British have in

fact come to an overdue recognition that the old version of multiculturalism

they formerly practiced was dangerous and counterproductive. Liberal tolerance

was interpreted as respect not for the rights of individuals, but of groups,

some of whom were themselves intolerant (by, for example, dictating whom their

daughters could befriend or marry). Out of a misplaced sense of respect for

other cultures, Muslims minorities were left to regulate their own behavior, an

attitude which dovetailed with a traditional European corporatist approaches to

social organization.

In Holland, where the state supports separate Catholic, Protestant and socialist

schools, it was easy enough to add a Muslim "pillar" that quickly turned into a

ghetto disconnected from the surrounding society.

New policies to reduce the separateness of the Muslim community, like laws

discouraging the importation of brides from the Middle East, have been put in

place in the Netherlands. The Dutch and British police have been given new

powers to monitor, detain and expel inflammatory clerics. But the much more

difficult problem remains of fashioning a national identity that will connect

citizens of all religions and ethnicities in a common democratic culture, as the

American creed has served to unite new immigrants to the United States.

Since van Gogh's murder, the Dutch have embarked on a vigorous and often

impolitic debate on what it means to be Dutch, with some demanding of immigrants

not just an ability to speak Dutch, but a detailed knowledge of Dutch history

and culture that many Dutch people do not have themselves.

But national identity has to be a source of inclusion, not exclusion; nor can it

be based, contrary to the assertion of the gay Dutch politician Pym Fortuyn who

was assassinated in 2003, on endless tolerance and valuelessness. The Dutch have

at least broken through the stifling barrier of political correctness that has

prevented most other European countries from even beginning a discussion of the

interconnected issues of identity, culture and immigration. But getting the

national identity question right is a delicate and elusive task. Many Europeans

assert that the American melting pot cannot be transported to European soil.

Identity there remains rooted in blood, soil and ancient shared memory. This may

be true, but if so, democracy in Europe will be in big trouble in the future as

Muslims become an ever larger percentage of the population. And since Europe is

today one of the main battlegrounds of the war on terrorism, this reality will

matter for the rest of us as well.

Muslim Nations Unable to Endorse Democracy

By STEVEN R. WEISMAN

November 13, 2005

NY Times

MANAMA,

Bahrain, Nov. 12 - A meeting of Muslim nations initiated by the Bush

administration ended in discord on Saturday after objections by Egypt

blocked a final declaration supporting democracy.

The administration did, however, get backing for a $50 million

foundation to support political activities in the Muslim world, with

money to be raised from American, European and Arab sources, and a $100

million fund half financed by the United States to provide venture

capital to businesses.

Diplomats at the conference said Egypt wanted the language in the

meeting's final declaration to say that only "legally registered"

groups should be aided by the foundation.

The Americans expressed open irritation with Egypt for its efforts to

"scuttle," as one put it, what they had hoped would be a milestone in

its efforts to promote democracy in the Middle East.

"Obviously, we are not pleased," a senior State Department official

said. Another said, in a tone of exasperation, "I don't understand why

they should make this an issue." Both declined to be identified because

they did not want to criticize Egypt directly.

Egyptian diplomats have complained that outside financing for groups

may end up in the hands of extremists or even terrorists. American

officials dismiss those warnings as absurd, noting that some American

aid to Egypt, about $430 million this year, already goes to groups in

Egypt that do not have government approval.

But American support for independent groups in other countries has

alarmed some Arab leaders. They cite American aid that supported groups

that led the uprisings in Georgia and Ukraine and point out that both

Russia and Uzbekistan have sought to block American aid to groups in

their countries.

Since President Bush's inaugural address in January calling for the

sweeping adoption of democratic rule in autocratic countries, the

administration has pressed more and more for aid to the Middle East to

go, at least in part, to groups supporting change in their societies,

with training, subsidies and such mundane things as printing presses.

The administration first set up its own Middle East Partnership

Initiative, which committed $300 million in aid in the last few years

to political and business activity in the region.

Now, in part to remove American fingerprints in a region where

anti-American sentiments run high, about $85 million is to be taken out

of this initiative and used for the new Foundation for the Future, for

support of democratic groups, and the Fund for the Future, for

entrepreneurial efforts. Both are part of the Bush administration's

so-called Broader Middle East and North Africa initiative, set up in

the meeting of the major industrial democracies at Sea Island, Ga., in

mid-2004.

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, in remarks at the session of the

conference, hailed the foundation's establishment, which had been

negotiated for a year and a half, saying it "will provide grants to

help civil society strengthen the rule of law, to protect basic civil

liberties and ensure greater opportunity for health and education."

Some delegates to the meeting saw Egypt's objections as a reflection of

the Arab world's growing irritation with what some say is the lecturing

tone of American calls for democracy. United States involvement in Iraq

plays a part in that: the Arab world is not persuaded by the

administration's portrayal of Iraq, which Secretary Rice visited on

Friday, as a beacon for democracy.

Rather, they say, Iraq represents the perils of imposing democracy from

outside. Its violence is widely seen as offering a cautionary tale

rather than an inspiration, American officials acknowledge.

Egypt represents more than half the population of the Arab world and is

often a leader of its political concerns, particularly in pressing for

more attention to be paid in the West to the tensions between Israel

and the Palestinians. The disagreement also appeared to reflect a

difficult phase in American-Egyptian relations, which have been ruffled

by American demands for greater openness in the Egyptian political

process.

Egypt rejected an American suggestion for international monitors for

its recent presidential election, for example, and complained that it

was not receiving credit for conducting its first multiparty elections

and for allowing more dissident political activity.

The Egyptian foreign minister, Ahmed Aboul Gheit, left the conference

early, declining to join in the final photograph and working lunch,

brushing off questions about the final document, telling reporters that

there was no such thing, even though a draft had been circulating all

day.

But Amr Moussa, a former Egyptian foreign minister who is president of

the Arab League, said the final document supporting democracy did not

reflect the meeting's consensus. "If a statement is imposed, nobody

will give it any consideration," he said.

Egypt's criticism was initially backed by Saudi Arabia and the Persian

Gulf country of Oman, but both supported the United States in the end,

American diplomats said. They added that with 40 nongovernmental

organizations in Bahrain demanding support, they could not delete the

reference to such groups in the final declaration without drawing even

more criticism.

Bahrain's foreign minister, Sheik Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa, who

presided over the session on Saturday, said at a news conference that

Egypt's objections could not be ironed out because they were presented

at the last moment. "We don't want this to be a haphazard decision," he

said. A draft of the final declaration was prepared more than a month

ago, at a meeting in Rabat, Morocco. Mr. Khalifa said a draft might be

adopted in a year at the next meeting, in Amman, Jordan.

Islam and Western

Democracies

Legatus Summit, Naples, Florida U.S.A

By Cardinal George Pell

Archbishop of Sydney

September 11 was a wake-up call for me personally. I recognised that I had to

know more about Islam.

In the aftermath of the attack one thing was perplexing. Many commentators and

apparently the governments of the "Coalition of the Willing" were claiming that

Islam was essentially peaceful, and that the terrorist attacks were an

aberration. On the other hand one or two people I met, who had lived in Pakistan

and suffered there, claimed to me that the Koran legitimised the killings of

non-Muslims.

Although I had possessed a copy of the Koran for 30 years, I decided then to

read this book for myself as a first step to adjudicating conflicting claims.

And I recommend that you too read this sacred text of the Muslims, because the

challenge of Islam will be with us for the remainder of our lives - at least.

Can Islam and the Western democracies live together peacefully? What of Islamic

minorities in Western countries? Views on this question range from näive

optimism to bleakest pessimism. Those tending to the optimistic side of the

scale seize upon the assurance of specialists that jihad is primarily a matter

of spiritual striving, and that the extension of this concept to terrorism is a

distortion of koranic teaching[1]. They emphasise Islam's self-understanding as

a "religion of peace". They point to the roots Islam has in common with Judaism

and Christianity and the worship the three great monotheistic religions offer to

the one true God. There is also the common commitment that Muslims and

Christians have to the family and to the defence of life, and the record of

co-operation in recent decades between Muslim countries, the Holy See, and

countries such as the United States in defending life and the family at the

international level, particularly at the United Nations.

Many commentators draw attention to the diversity of Muslim life-sunni, shi'ite,

sufi, and their myriad variations-and the different forms that Muslim devotion

can take in places such as Indonesia and the Balkans on the one hand, and Iran

and Nigeria on the other. Stress is laid, quite rightly, on the widely divergent

interpretations of the Koran and the shari'a, and the capacity Islam has shown

throughout its history for developing new interpretations. Given the

contemporary situation, the wahhabist interpretation at the heart of Saudi

Islamism offers probably the most important example of this, but Muslim history

also offers more hopeful examples, such as the re-interpretation of the shari'a

after the fall of the Ottoman empire, and particularly after the end of the

Second World War, which permitted Muslims to emigrate to non-Muslim

countries[2].

Optimists also take heart from the cultural achievements of Islam in the Middle

Ages, and the accounts of toleration extended to Jewish and Christian subjects

of Muslim rule as "people of the Book". Some deny or minimise the importance of

Islam as a source of terrorism, or of the problems that more generally afflict

Muslim countries, blaming factors such as tribalism and inter-ethnic enmity; the

long-term legacy of colonialism and Western domination; the way that oil

revenues distort economic development in the rich Muslim states and sustain

oligarchic rule; the poverty and political oppression in Muslim countries in

Africa; the situation of the Palestinians, and the alleged "problem" of the

state of Israel; and the way that globalisation has undermined or destroyed

traditional life and imposed alien values on Muslims and others.

Indonesia and Turkey are pointed to as examples of successful democratisation in

Muslim societies, and the success of countries such as Australia and the United

States as "melting pots", creating stable and successful societies while

absorbing people from very different cultures and religions, is often invoked as

a reason for trust and confidence in the growing Muslim populations in the West.

The phenomenal capacity of modernity to weaken gradually the attachment of

individuals to family, religion and traditional ways of life, and to commodify

and assimilate developments that originate in hostility to it (think of the way

the anti-capitalist counter-culture of the 1960s and 70s was absorbed into the

economic and political mainstream-and into consumerism), is also relied upon to

"normalise" Muslims in Western countries, or at least to normalise them in the

minds of the non-Muslim majority.

Reasons for optimism are also sometimes drawn from the totalitarian nature of

Islamist ideology, and the brutality and rigidity of Islamist rule, exemplified

in Afghanistan under the Taliban. Just as the secular totalitarian-isms of the

twentieth century (Nazism and Communism) ultimately proved unsustainable because

of the enormous toll they exacted on human life and creativity, so too will the

religious totalitarianism of radical Islam. This assessment draws on a more

general underlying cause for optimism, or at least hope, for all of us, namely

our common humanity, and the fruitfulness of dialogue when it is entered with

good will on all sides. Most ordinary people, both Muslim and non-Muslim, share

the desire for peace, stability and prosperity for themselves and their

families.

On the pessimistic side of the equation, concern begins with the Koran itself.

In my own reading of the Koran, I began to note down invocations to violence.

There are so many of them, however, that I abandoned this exercise after 50 or

60 or 70 pages. I will return to the problems of Koranic interpretation later in

this paper, but in coming to an appreciation of the true meaning of jihad, for

example, it is important to bear in mind what the scholars tell us about the

difference between the suras (or chapters) of the Koran written during

Muhammad's thirteen years in Mecca, and those that were written after he had

based himself at Medina. Irenic interpretations of the Koran typically draw

heavily on the suras written in Mecca, when Muhammad was without military power

and still hoped to win people, including Christians and Jews, to his revelation

through preaching and religious activity. After emigrating to Medina, Muhammad

formed an alliance with two Yemeni tribes and the spread of Islam through

conquest and coercion began[3]. One calculation is that Muhammad engaged in 78

battles, only one of which, the Battle of the Ditch, was defensive[4]. The suras

from the Medina period reflect this decisive change and are often held to

abrogate suras from the Meccan period[5].

The predominant grammatical form in which jihad is used in the Koran carries the

sense of fighting or waging war. A different form of the verb in Arabic means

"striving" or "struggling", and English translations sometimes use this form as

a way of euphemistically rendering the Koran's incitements to war against

unbelievers[6]. But in any case, the so-called "verses of the sword" (sura 95

and 936)[7], coming as they do in what scholars generally believe to be one of

the last suras revealed to Muhammad[8], are taken to abrogate a large number of

earlier verses on the subject (over 140, according to one radical website[9]).

The suggestion that jihad is primarily a matter of spiritual striving is also

contemptuously rejected by some Islamic writers on the subject. One writer warns

that "the temptation to reinterpret both text and history to suit 'politically

correct' requirements is the first trap to be avoided", before going on to

complain that "there are some Muslims today, for instance, who will convert

jihad into a holy bath rather than a holy war, as if it is nothing more than an

injunction to cleanse yourself from within"[10].

The abrogation of many of the Meccan suras by the later Medina suras affects

Islam's relations with those of other faiths, particularly Christians and Jews.

The Christian and Jewish sources underlying much of the Koran[11] are an

important basis for dialogue and mutual understanding, although there are

difficulties. Perhaps foremost among them is the understanding of God. It is

true that Christianity, Judaism and Islam claim Abraham as their Father and the

God of Abraham as their God. I accept with reservations the claim that Jews,

Christians and Muslims worship one god (Allah is simply the Arabic word for god)

and there is only one true God available to be worshipped! That they worship the

same god has been disputed[12], not only by Catholics stressing the triune

nature of God, but also by some evangelical Christians and by some Muslims[13].

It is difficult to recognise the God of the New Testament in the God of the

Koran, and two very different concepts of the human person have emerged from the

Christian and Muslim understandings of God. Think, for example, of the Christian

understanding of the person as a unity of reason, freedom and love, and the way

these attributes characterise a Christian's relationship with God. This has had

significant consequences for the different cultures that Christianity and Islam

have given rise to, and for the scope of what is possible within them. But these

difficulties could be an impetus to dialogue, not a reason for giving up on it.

The history of relations between Muslims on the one hand and Christians and Jews

on the other does not always offer reasons for optimism in the way that some

people easily assume. The claims of Muslim tolerance of Christian and Jewish

minorities are largely mythical, as the history of Islamic conquest and

domination in the Middle East, the Iberian peninsula and the Balkans makes

abundantly clear. In the territory of modern-day Spain and Portugal, which was

ruled by Muslims from 716 and not finally cleared of Muslim rule until the

surrender of Granada in 1491 (although over half the peninsula had been

reclaimed by 1150, and all of the peninsula except the region surrounding

Granada by 1300), Christians and Jews were tolerated only as dhimmis[14],

subject to punitive taxation, legal discrimination, and a range of minor and

major humiliations. If a dhimmi harmed a Muslim, his entire community would

forfeit protection and be freely subject to pillage, enslavement and murder.

Harsh reprisals, including mutilations, deportations and crucifixions, were

imposed on Christians who appealed for help to the Christian kings or who were

suspected of having converted to Islam opportunistically. Raiding parties were

sent out several times every year against the Spanish kingdoms in the north, and

also against France and Italy, for loot and slaves. The caliph in Andalusia

maintained an army of tens of thousand of Christian slaves from all over Europe,

and also kept a harem of captured Christian women. The Jewish community in the

Iberian peninsula suffered similar sorts of discriminations and penalties,

including restrictions on how they could dress. A pogrom in Granada in 1066

annihilated the Jewish population there and killed over 5000 people. Over the

course of its history Muslim rule in the peninsula was characterised by

outbreaks of violence and fanaticism as different factions assumed power, and as

the Spanish gradually reclaimed territory[15].

Arab rule in Spain and Portugal was a disaster for Christians and Jews, as was

Turkish rule in the Balkans. The Ottoman conquest of the Balkans commenced in

the mid-fifteenth century, and was completed over the following two hundred

years. Churches were destroyed or converted into mosques, and the Jewish and

Christians populations became subject to forcible relocation and slavery. The

extension or withdrawal of protection depended entirely on the disposition of

the Ottoman ruler of the time. Christians who refused to apostatize were taxed

and subject to conscript labour. Where the practice of the faith was not

strictly prohibited, it was frustrated-for example, by making the only legal

market day Sunday. But violent persecution was also a constant shadow. One

scholar estimates that up to the Greek War of Independence in 1828, the Ottomans

executed eleven Patriarchs of Constantinople, nearly one hundred bishops and

several thousand priests, deacons and monks. Lay people were prohibited from

practising certain professions and trades, even sometimes from riding a horse

with a saddle, and right up until the early eighteenth century their adolescent

sons lived under the threat of the military enslavement and forced conversion

which provided possibly one million janissary soldiers to the Ottomans during

their rule. Under Byzantine rule the peninsula enjoyed a high level of economic

productivity and cultural development. This was swept away by the Ottoman

conquest and replaced with a general and protracted decline in productivity[16].

The history of Islam's detrimental impact on economic and cultural development

at certain times and in certain places returns us to the nature of Islam itself.

For those of a pessimistic outlook this is probably the most intractable problem

in considering Islam and democracy. What is the capacity for theological

development within Islam?

In the Muslim understanding, the Koran comes directly from God, unmediated.

Muhammad simply wrote down God's eternal and immutable words as they were

dictated to him by the Archangel Gabriel. It cannot be changed, and to make the

Koran the subject of critical analysis and reflection is either to assert human

authority over divine revelation (a blasphemy), or question its divine

character. The Bible, in contrast, is a product of human co-operation with

divine inspiration. It arises from the encounter between God and man, an

encounter characterised by reciprocity, which in Christianity is underscored by

a Trinitarian understanding of God (an understanding Islam interprets as

polytheism). This gives Christianity a logic or dynamic which not only favours

the development of doctrine within strict limits, but also requires both

critical analysis and the application of its principles to changed

circumstances. It also requires a teaching authority.

Of course, none of this has prevented the Koran from being subjected to the sort

of textual analysis that the Bible and the sacred texts of other religions have

undergone for over a century, although by comparison the discipline is in its

infancy. Errors of fact, inconsistencies, anachronisms and other defects in the

Koran are not unknown to scholars, but it is difficult for Muslims to discuss

these matters openly.

In 2004 a scholar who writes under the pseudonym Christoph Luxenberg published a

book in German setting out detailed evidence that the original language of the

Koran was a dialect of Aramaic known as Syriac. Syriac or Syro-Aramaic was the

written language of the Near East during Muhammad's time, and Arabic did not

assume written form until 150 years after his death. Luxenberg argues that the

Koran that has come down to us in Arabic is partially a mistranscription of the

original Syriac. A bizarre example he offers which received some attention at

the time his book was published is the Koran's promise that those who enter

heaven will be "espoused" to "maidens with eyes like gazelles"; eyes, that is,

which are intensely white and black (suras 4454 and 5220). Luxenberg's

meticulous analysis suggests that the Arabic word for maidens is in fact a

mistranscription of the Syriac word for grapes. This does strain common sense.

Valiant strivings to be consoled by beautiful women is one thing, but to be

heroic for a packet of raisins seems a bit much!

Even more explosively, Luxenberg suggests that the Koran has its basis in the

texts of the Syriac Christian liturgy, and in particular in the Syriac

lectionary, which provides the origin for the Arabic word "koran". As one

scholarly review observes, if Luxenberg is correct the writers who transcribed

the Koran into Arabic from Syriac a century and a half after Muhammad's death

transformed it from a text that was "more or less harmonious with the New

Testament and Syriac Christian liturgy and literature to one that [was]

distinct, of independent origin"[17]. This too is a large claim.

It is not surprising that much textual analysis is carried out pseudonymously.

Death threats and violence are frequently directed against Islamic scholars who

question the divine origin of the Koran. The call for critical consideration of

the Koran, even simply of its seventh-century legislative injunctions, is

rejected out of hand by hard-line Muslim leaders. Rejecting calls for the

revision of school textbooks while preaching recently to those making the hajj

pilgrimage to Mount Arafat, the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia told pilgrims that

"there is a war against our creed, against our culture under the pretext of

fighting terrorism. We should stand firm and united in protecting our religion.

Islam's enemies want to empty our religion [of] its content and meaning. But the

soldiers of God will be victorious"[18].

All these factors I have outlined are problems, for non-Muslims certainly, but

first and foremost for Muslims themselves. In grappling with these problems we

have to resist the temptation to reduce a complex and fluid situation to black

and white photos. Much of the future remains radically unknown to us. It is hard

work to keep the complexity of a particular phenomenon steadily in view and to

refuse to accept easy answers, whether of an optimistic or pessimistic kind.

Above all else we have to remember that like Christianity, Islam is a living

religion, not just a set of theological or legislative propositions. It animates

the lives of an estimated one billion people in very different political, social

and cultural settings, in a wide range of devotional styles and doctrinal

approaches. Human beings have an invincible genius for variation and innovation.

Considered strictly on its own terms, Islam is not a tolerant religion and its

capacity for far-reaching renovation is severely limited. To stop at this

proposition, however, is to neglect the way these facts are mitigated or

exacerbated by the human factor. History has more than its share of surprises.

Australia lives next door to Indonesia, the country with one of the largest

Muslim populations in the world[19]. Indonesia has been a successful democracy,

with limitations, since independence after World War II. Islam in Indonesia has

been tempered significantly both by indigenous animism and by earlier Hinduism

and Buddhism, and also by the influence of sufism. As a consequence, in most of

the country (except in particular Aceh) Islam is syncretistic, moderate and with

a strong mystical leaning. The moderate Islam of Indonesia is sustained and

fostered in particular by organisations like Nahdatul Ulama, once led by former

president Abdurrahman Wahid, which runs schools across the country, and which

with 30-40 million members is one of the largest Muslim organisations in the

world.

The situation in Indonesia is quite different from that in Pakistan, the country

with one of the largest Muslim populations in the world. 75 per cent of

Pakistani Muslims are Sunni, and most of these adhere to the relatively

more-liberal Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence (for example, Hanafi

jurisprudence does not consider blasphemy should be punishable by the state).

But religious belief in Pakistan is being radicalised because organisations,

very different from Indonesia's Nahdatul Ulama, have stepped in to fill the void

in education created by years of neglect by military rulers. Pakistan spends

only 1.8 per cent of GDP on education. 71 per cent of government schools are

without electricity, 40 per cent are without water, and 15 per cent are without

a proper building. 42 per cent of the population is literate, and this

proportion is falling. This sort of neglect makes it easy for radical Islamic

groups with funding from foreign countries to gain ground. There has been a

dramatic increase in the number of religious schools (or madrasas) opening in

Pakistan, and it is estimated that they are now educating perhaps 800,000

students, still a small proportion of the total, but with a disproportionate

impact[20].

These two examples show that there is a whole range of factors, some of them

susceptible to influence or a change in direction, affecting the prospects for a

successful Islamic engagement with democracy. Peace with respect for human

rights are the most desirable end point, but the development of democracy will

not necessarily achieve this or sustain it. This is an important question for

the West as well as for the Muslim world. Adherence to what George Weigel has

called "a thin, indeed anorexic, idea of procedural democracy"[21] can be fatal

here. It is not enough to assume that giving people the vote will automatically

favour moderation, in the short term at least[22]. Moderation and democracy have

been regular partners in Western history, but have not entered permanent and

exclusive matrimony and there is little reason for this to be better in the

Muslim world, as the election results in Iran last June and the elections in

Palestine in January reminded us. There are many ways in which President Bush's

ambition to export democracy to the Middle East is a risky business. In its

influence on both religion and politics, the culture is crucial.

There are some who resist this conclusion vehemently. In 2002, the Nobel Prize

Economist Amartya Sen took issue with the importance of culture in understanding

the radical Islamic challenge, arguing that religion is no more important than

any other part or aspect of human endeavour or interest. He also challenged the

idea that within culture religious faith typically plays a decisive part in the

development of individual self-understanding. Against this, Sen argued for a

characteristically secular understanding of the human person, constituted above

all else by sovereign choice. Each of us has many interests, convictions,

connections and affiliations, "but none of them has a unique and pre-ordained

role in defining [the] person". Rather, "we must insist upon the liberty to see

ourselves as we would choose to see ourselves, deciding on the relative

importance that we would like to attach to our membership in the different

groups to which we belong. The central issue, in sum, is freedom".[23]

This does work for some, perhaps many, people in the rich, developed and highly

urbanised Western world, particularly those without strong attachments to

religion. Doubtless it has ideological appeal to many more among the elites. But

as a basis for engagement with people of profound religious conviction, most of

whom are not fanatics or fundamentalists, it is radically deficient. Sen's words

demonstrate that the high secularism of our elites is handicapped in

comprehending the challenge that Islam poses.

I suspect one example of the secular incomprehension of religion is the blithe

encouragement of large scale Islamic migration into Western nations,

particularly in Europe. Of course they were invited to meet the need for labour

and in some cases to assuage guilt for a colonial past.

If religion rarely influences personal behaviour in a significant way then the

religious identity of migrants is irrelevant. I suspect that some

anti-Christians, for example, the Spanish Socialists, might have seen Muslims as

a useful counterweight to Catholicism, another factor to bring religion into

public disrepute. Probably too they had been very confident that Western

advertising forces would be too strong for such a primitive religious viewpoint,

which would melt down like much of European Christianity. This could prove to be

a spectacular misjudgement.

So the current situation is very different from what the West confronted in the

twentieth century Cold War, when secularists, especially those who were

repentant communists, were well equipped to generate and sustain resistance to

an anti-religious and totalitarian enemy. In the present challenge it is

religious people who are better equipped, at least initially, to understand the

situation with Islam. Radicalism, whether of religious or non-religious

inspiration, has always had a way of filling emptiness. But if we are going to

help the moderate forces within Islam defeat the extreme variants it has thrown

up, we need to take seriously the personal consequences of religious faith. We

also need to understand the secular sources of emptiness and despair and how to

meet them, so that people will choose life over death. This is another place

where religious people have an edge. Western secularists regularly have trouble

understanding religious faith in their own societies, and are often at sea when

it comes to addressing the meaninglessness that secularism spawns. An anorexic

vision of democracy and the human person is no match for Islam.

It is easy for us to tell Muslims that they must look to themselves and find

ways of reinterpreting their beliefs and remaking their societies. Exactly the

same thing can and needs to be said to us. If democracy is a belief in

procedures alone then the West is in deep trouble. The most telling sign that

Western democracy suffers a crisis of confidence lies in the disastrous fall in

fertility rates, a fact remarked on by more and more commentators. In 2000,

Europe from Iceland to Russia west of the Ural Mountains recorded a fertility

rate of only 1.37. This means that fertility is only at 65 per cent of the level

needed to keep the population stable. In 17 European nations that year deaths

outnumbered births. Some regions in Germany, Italy and Spain already have

fertility rates below 1.0.

Faith ensures a future. As an illustration of the literal truth of this,

consider Russia and Yemen. Look also at the different birth rates in the red and

blue states in the last presidential election in the U.S.A. In 1950 Russia,

which suffered one of the most extreme forms of forced secularisation under the

Communists, had about 103 million people. Despite the devastation of wars and

revolution the population was still young and growing. Yemen, a Muslim country,

had only 4.3 million people. By 2000 fertility was in radical decline in Russia,

but because of past momentum the population stood at 145 million. Yemen had

maintained a fertility rate of 7.6 over the previous 50 years and now had 18.3

million people. Median level United Nations forecasts suggest that even with

fertility rates increasing by 50 per cent in Russia over the next fifty years,

its population will be about 104 million in 2050-a loss of 40 million people. It

will also be an elderly population. The same forecasts suggest that even if

Yemen's fertility rate falls 50 per cent to 3.35, by 2050 it will be about the

same size as Russia - 102 million - and overwhelmingly young[24].

The situation of the United States and Australia is not as dire as this,

although there is no cause for complacency. It is not just a question of having

more children, but of rediscovering reasons to trust in the future. Some of the

hysteric and extreme claims about global warming are also a symptom of pagan

emptiness, of Western fear when confronted by the immense and basically

uncontrollable forces of nature. Belief in a benign God who is master of the

universe has a steadying psychological effect, although it is no guarantee of

Utopia, no guarantee that the continuing climate and geographic changes will be

benign. In the past pagans sacrificed animals and even humans in vain attempts

to placate capricious and cruel gods. Today they demand a reduction in carbon

dioxide emissions.

Most of this is a preliminary clearing of the ground for dialogue and

interaction with our Muslim brothers and sisters based on the conviction that it

is always useful to know accurately where you are before you start to decide

what you should be doing.

The war against terrorism is only one aspect of the challenge. Perhaps more

important is the struggle in the Islamic world between moderate forces and

extremists, especially when we set this against the enormous demographic shifts

likely to occur across the world, the relative changes in population-size of the

West, the Islamic and Asian worlds and the growth of Islam in a childless

Europe.

Every great nation and religion has shadows and indeed crimes in their

histories. This is certainly true of Catholicism and all Christian

denominations. We should not airbrush these out of history, but confront them

and then explain our present attitude to them.

These are also legitimate requests for our Islamic partners in dialogue. Do they

believe that the peaceful suras of the Koran are abrogated by the verses of the

sword? Is the programme of military expansion (100 years after Muhammad's death

Muslim armies reached Spain and India) to be resumed when possible?

Do they believe that democratic majorities of Muslims in Europe would impose

Sharia law? Can we discuss Islamic history and even the hermeneutical problems

around the origins of the Koran without threats of violence?

Obviously some of these questions about the future cannot be answered, but the

issues should be discussed. Useful dialogue means that participants grapple with

the truth and in this issue of Islam and the West the stakes are too high for

fundamental misunderstandings.

Both Muslims and Christians are helped by accurately identifying what are core

and enduring doctrines, by identifying what issues can be discussed together

usefully, by identifying those who are genuine friends, seekers after truth and

cooperation and separating them from those who only appear to be friends.

NOTES:

[1]. For some examples of this, see Daniel Pipes, "Jihad and the Professors",

Commentary, November 2002.

[2]. For an account of how some Muslim jurists dealt with large-scale emigration

to non-Muslim countries, see Paul Stenhouse MSC, "Democracy, Dar al-Harb, and

Dar al-Islam", unpublished manuscript, nd.

[3]. Paul Stenhouse MSC, "Muhammad, Qur'anic Texts, the Shari'a and Incitement

to Violence". Unpublished manuscript, 31 August 2002.

[4]. Daniel Pipes "Jihad and the Professors" 19. Another source estimates that

Muhammad engaged in 27 (out of 38) battles personally, fighting in 9 of them.

See A. Guillaume, The Life of Muhammad by Ibn Ishaq (Oxford University Press,

Karachi: 1955), 659.

[5]. Stenhouse "Muhammad, Qur'anic Texts, the Shari'a and Incitement to

Violence".

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. Sura 95: "Then, when the sacred months are drawn away, slay the idolaters

wherever you find them, and take them, and confine them, and lie in wait for

them at every place of ambush. But if they repent, and perform the prayer, and

pay the alms, then let them go their way; for God is All-forgiving,

All-compassionate."

Sura936: "And fight the unbelievers totally even as they fight you totally; and

know that God is with the godfearing." (Arberry translation).

[8]. Richard Bonney, Jihad: From Qur'an to bin Laden (Palgrave, Hampshire:

2004), 22-26.

[9]."The Will of Abdullaah Yusuf Azzam",

www.islamicawakening.com/viewarticle.php? articleID=532& (dated 20 April

1986).

[10]. M. J. Akbar, The Shade of Swords: Jihad and the Conflict between Islam and

Christianity (Routledge, London & New York: 2002), xv.

[11]. Abraham I. Katsch, Judaism and the Koran (Barnes & Co., New York: 1962),

passim.

[12]. See for example Alain Besançon, "What Kind of Religion is Islam?"

Commentary, May 2004.

[13]. Daniel Pipes, "Is Allah God?" New York Sun, 28 June 2005.

[14]. On the concept of "dhimmitude", see Bat Ye'or, The Decline of Eastern

Christianity under Islam: From Jihad to Dhimmitude, trans. Miriam Kochman and

David Littman (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Madison NJ: 1996).

[15]. Andrew Bostom, The Legacy of Jihad: Islamic Holy War and the Fate of Non

Muslims (Prometheus Books, Amherst NY: 2005), 56-75.

[16]. Ibid.

[17]. Robert R. Phenix Jr & Cornelia B. Horn, "Book Review of Christoph

Luxenberg (ps.) Die syro-aramaeische Lesart des Koran: Ein Beitrag zur

Entschlüsselung der Qur'ansprache", Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, 6:1

(January 2003). See also the article on Luxenberg's book published in Newsweek,

28 July 2004.

[18]. "Hajj Pilgrims Told of War on Islam",

www.foxnews.com, 9 January 2006.

[19]. The World Christian Database (http://worldchristian

database.org) gives a considerably lower estimate of the Muslim proportion of

the population (54 per cent, or 121.6 million), attributing 22 per cent of the

population to adherents of Asian "New Religions". On the WCD's estimates,

Pakistan has the world's largest Muslim population, with 154.5 million (or

approximately 96 per cent of a total population of 161 million). The CIA's World

Fact Book (http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook)

estimates 88 per cent of Indonesia's population of 242 million is Muslim, giving

it a Muslim population of 213 million.

The Muslim proportion of the population in Indonesia may be as low as 37-40 per

cent, owing to the way followers of traditional Javanese mysticism are

classified as Muslim by government authorities. See Paul Stenhouse MSC,

"Indonesia, Islam, Christians, and the Numbers Game", Annals Australia, October

1998.

[20]. William Dalrymple, "Inside the Madrasas", New York Review of Books, 1

December 2005.

[21]. George Weigel, The Cube and the Cathedral: Europe, America and Politics

without God (Basic Books, New York: 2005), 136.

[22]. For a sophisticated presentation of the argument of the case for the

moderating effect of electoral democracy in the Islamic world, see the Pew

Forum's interview with Professor Vali Nasr (Professor of National Security

Studies at the US Naval Postgraduate School),"Islam and Democracy: Iraq,

Afghanistan and Pakistan", 4 November 2005,

http://pewforum.org/events/index.php?EventID=91.

[23]. Amartya Sen, "Civilizational Imprisonments", The New Republic, 10 June

2002.

[24]. Allan Carlson, "Sweden and the Failure of European Family Policy",

Society, September-October 2005. :: Home | Go back | Top of Page | Site Map |

Copyright Copyright 19

Democracy vs. terrorism

Vikram Sood

August 25, 2006

In the second part of his column, former R&AW chief Vikram Sood explains why there can be no final victory in any battle against terrorism.

Post 9/11 and particularly post-Madrid 2004, events have led to a hardening of positions in Europe among the majority population and, at the same time, there are more second and third generation Muslim youth finding their way to jihad. The stereotype of the jihadi coming from the Arab world is changing. Post-September 11, recruits are just as easily to be found in poly-techniques, high schools and university campuses in Europe.

Hundreds of European youth, mainly second generation immigrants, have found their way to Iraq to fight in the Sunni triangle. There were reports of a two-way traffic between West Asia and Europe of illegals coming in to Europe and legals going to perform jihad in faraway places. Three of the July bombers in London were young second-generation youth of Pakistani parentage. The youth in the UK have been increasingly under the influence of the Deobandi mosques, where al Qaeda, Lashkar-e-Tayiba, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Hizbut Tehrir activists have been active.

In Europe, intelligence and police officials from the UK, Spain, Germany, France and the Netherlands meet in state-of-the-art environments to exchange information and data, reports and wiretaps that would help follow leads in their anti-terror effort. Cooperation on this scale or even at a much lower scale is unthinkable on the Indian subcontinent, as this would be counterproductive to policies followed by the Pakistani establishment. Indo-Pak talks on curbing terror are more a dialogue of the deaf than a purposeful discussion.

Post-World War II European liberalism, that had tolerated other religions and political beliefs, is today threatened with an immigrant Muslim population that constitutes four to five per cent of the population (European census usually does not ask for religion). This is expected to go up to ten per cent by 2025, and the indigenous population is expected to decline.

So long as multi-culturalism did not affect Europe's way of life, immigration was acceptable, but once it became clear that this being taken advantage of by the immigrant and seen as encouraging terrorism, restrictions have begun to be applied. This push of immigrants from Asia brings its own social problems. This aspect is going to be a major cause for concern in Europe in the years ahead.

The ferment in the entire Muslim world creates the impression of a monolith with one common remedy or a set of common remedies to the problem. The Muslim ummah did get together in the Afghan jihad, and now seems to be getting together again post-Iraq, and even more strongly should there be a post-Iran, but there are continuing differences and Muslims still kill Muslims in defence of the same religion.

It is also assumed that Osama is the symbol of this ferment. He has been glorified into a cult figure, but he is not really the single unifying factor in the Muslim world. There are many who are anti-US and anti-Israel, but who feel that al Qaeda over-reached by attacking the US, which invited massive US military retaliation and the occupation of Muslim lands.

A new ideologue for the Islamists seems to have been active in recent years. Born in Syria and hiding in Pakistan, 48-year old Mustafa Setmariam Nasar turned out volumes on the Net arguing that with the Afghan base having been lost, Islamic radicals would have to revise their approach.

His thesis, in a 1600-page work called The Call for a Global Islamic Renaissance, has been in circulation on the Internet for 18 months, and its thrust is that a truly global conflict should be on several fronts, carried out by small cells or individuals rather than traditional guerrilla warfare. Nasar was arrested in Quetta last October and handed over to US officials, but his creed continues to be assimilated and followed.

The problem is not in the Pakistani madrassas alone. Jihad continues to be taught in mainstream schools even today. Hatred towards other religions and towards India is a common diet. The worry is that while most of the madrassa alumni end up in the caves of Tora Bora or the heights of Parachinar, those from mainstream schools go to mainstream colleges and end up with main line jobs at home or abroad. Assuming that three million school children are added to Pakistan's schools every year, an unknown number of the 70 million young persons have already imbibed jihadi leanings in the last 25 years.

The centre of jihad at the time of September 11 was in Afghanistan, specifically in the Pushtoon belt between Kandahar and Jalalabad. Since then, in the face of the American onslaught, the epicenter for international jihad for the rest of the world (except West Asia) is now in Pakistani Waziristan.

The Taliban, resurgent in Afghanistan from sanctuaries in the turbulent Waziristan of Pakistan, have been sending their volunteers to Iraq for training in suicide terrorism and arms. Waziristan is also a sanctuary for Chechens and Uzbek Islamic insurgents. The recent spectacular comeback of the Taliban in southern and eastern Afghanistan, operating from their sanctuaries in Pakistan where they have declared an Islamic Republic of Waziristan, has been achieved with help from al Qaeda operatives, Gulbuddin Hikmetyar's Hizb-e-Islami and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan.

It is probably more accurate to say that today, Mullah Omar commands more dedicated battalions than does Osama, whose followers are dispersed in concept, space and even ideology.

More dangerous than al Qaeda in the Indian context are the activities of the International Islamic Front established by Osama in February 1998. Five Pakistani terrorist organizations are signatories to this IIF � HuM, LeT, Harkat-ul-Jehadi-ul-Islami , JEM and LeJ � all Sunni, all anti-Christian, anti-Jew and anti-Hindu, and all continually exhorting the destruction of India and prophesying victory over Jews and Christians.

Another centre is Bangladesh, where jihadi organizations propagate jihadi terrorism in India and South-east Asia. The location of the continuing jihad against Christians, Jews and Hindus can be anywhere. It will be where the jihadis feel that it would be easier to operate and have the maximum impact. This obviously makes the US and Europe the most likely targets.

Groups like al Qaeda and LeT cannot be controlled by a purely non-military response because they seek the establishment of Caliphates, through violence if necessary, and this is not acceptable in the modern world. It is necessary to militarily weaken these forces, starve them of funds and bases and then to tackle long-term issues by providing them better education, employment and so on.

While discussing the roots of terrorism in his book No End to this War, Walter Laqueur says Muslims have had a problem adjusting as minorities, be it in India, the Philippines or Western Europe. Similarly, they find it difficult to give their own minorities, whether Muslim or non-Muslim, a fair deal in their own countries � the Berbers in Algeria, the Copts in Egypt or the Christians or Shias in Pakistan or Sudan being examples.

This has in turn led to what Olivier Roy calls globalized Islam � militant Islamic resentment at Western domination or anti-Imperialism exalted by revivalism. State sponsorship of terrorism, as an instrument of foreign policy and strategy to negate military and other superiority, has been another facet of this problem.

There is a naive assumption that if local grievances or problems are solved, global terrorism will disappear. The belief or the hope that, if tomorrow, in Palestine, or Kashmir or Chechnya or wherever else, the issues were settled, terrorism will disappear, is a mistaken belief. There is now enough free-floating violence and vested interests that would need this violence to continue. There has been a multifaceted nexus between narcotics, illicit arms smuggling and human trafficking, that seeks the continuance of violence and disorder.

Modern terrorism thrives not on just ideology or politics. The main driver is money, and the new economy of terror and international crime has been calculated to be worth US $1.5 trillion (and growing), which is big enough to challenge Western hegemony. This is higher than the GDP of Britain, and ten times the size of General Motors.

Loretta Napoleoni splits this money into three parts. About one-third constitutes money that has moved illegally from one country to another; another one-third is generated primarily by criminal activities and called the Gross Criminal Product; and the remaining is the money produced by terror organizations, from legal businesses and from narcotics and smuggling. Napoleoni refers to this as the New Economy of Terror.

All the illegal businesses of arms and narcotics trading, oil and diamonds smuggling, charitable organizations that front for illegal businesses, and the black money operations form part of this burgeoning business. Terror has other reasons to thrive. There are vested interests that seek the wages of terrorism and terrorist war.

Narcotics smuggling generates its own separate business lines, globally connected with arms smuggling and human trafficking, and all dealt with in hundred dollar bills. These black dollars have to be laundered, which is yet another distinctive, secretive and complicated transnational occupation closely connected with these illegal activities, and is really a crucial infusion of cash into the Western economies.

The '90s were a far cry from the early days of dependence on the Cold War sponsors of violence and terrorism. In the '70s, terrorists began to rely on legal economic activities for raising funds. The buzzword today is globalization, including in the business of terrorism. Armed groups have linked up internationally and, financially and otherwise, been able to operate across borders, with Pakistani jihadis doing service in Chechnya and Kosovo, or Uzbek insurgents taking shelter in Pakistan.

In today's world of deregulated finance, terrorists have taken full advantage of systems to penetrate legitimate international financial institutions and establish regular business houses. Islamic banks and other charities have helped fund movements, sometimes without the knowledge of the managers of these institutions that the source and destination of the funds is not what has been declared. Both Hamas and the PLO have been flush with funds, with Arafat's secret treasury estimated to be worth US $ 700 million to US 2 billion.

It is not easy, but the civilized world must counter the scourge of terrorism. In a networked world, where communication and action can be in real time, where boundaries need not be crossed and where terrorist action can take place on the Net and through the Net, the task of countering this is increasingly difficult and intricate.

Governments are bound by Geneva Conventions in tackling a terrorist organization, whatever else Bush's aides may have told him, but the terrorist is not bound by such regulations in this asymmetric warfare.

The rest of the world cannot afford to see the US lose the war in Iraq, however ill-conceived it might have been. If the US cuts and runs, then the jihadis will proclaim victory over the sole superpower. If the US stays or extends its theatre of activity, this will only produce more jihadis. That is the dilemma for all of us.

Unfortunately, given the manner in which the US seeks to pursue its objectives, one is fairly certain that the US cannot win. What one is still not certain is whether or not there is a realization of this in Washington, or whether there is still a mood of self-denial and self-delusion.

It has to be accepted that there can be no final victory in any battle against terrorism. Resentments real or imagined, and exploding expectations, will remain. Since the state no longer has monopoly on instruments of violence, recourse to violence is increasingly a weapon of first resort. Terrorism can be contained and its effects minimized, but it cannot be eradicated, anymore than the world can eradicate crime.

An over-militaristic response or repeated use of the armed forces is fraught with long-term risks for a nation and for its forces. Military action to deter or overcome an immediate threat is often necessary, but it cannot ultimately eradicate terrorism. This is as much a political and economic battle, and also a battle to be fought long-term by the intelligence and security agencies, increasingly in cooperation with agencies of other countries.

Ultimately, the battle is between democracy and terrorism. The fear is that in order to defeat the latter, we may be losing some of our democratic values.

Vikram Sood is a former chief of Research and Analysis Wing, India's foreign intelligence agency.

Instituting Democracy in Islamic Nations

The reasons for difficulties lie in fundamental principles of Islam

December 7, 2006

In the post-9/11

era, the Bush administration's new project of spreading freedom and

democracy to countries ruled by dictators became one of the most

discussed and closely followed topics in the media, and at all levels

of society.

As the world faces the violence unleashed by Islamist terrorist groups,

seeking out a way to turn the tide towards peace was indeed a desirable

idea. Although many doubted the means the Bush administration undertook

to spread democracy around the world, few disagreed with the fact that

freedom and democracy can usher in peace and prosperity.

Believing in this fundamental premise, many in the U.S. and around the world

supported the Bush administration's aggressive policy of instituting democracy

by overthrowing the authoritarian governments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

However, the adventure of spreading democracy has yet to succeed in those two

countries. All indications suggest that it will never be successful. It seems

that what we are witnessing today is the failure of the Bush administration's

policy of spreading democracy. Not only that, these countries have, instead,

become massive breeding grounds for the terrorists and the world is in a poorer

condition as far as threats from such violent groups are concerned.

As it appears now, the skeptics of the Bush administration's policy of exporting

democracy, who had argued that democracy cannot be exported or imposed on a

people from outside, might have been right. They have argued that freedom and

democracy have to evolve from within. So we can safely say that these skeptics

were right and the Bush administration's war architects were utterly wrong.

Upfront, I want to assert that both the skeptics of the Bush formula as well as

its supporters are only partially right and partially wrong.

Can democracy be imposed from without? It is a stale analysis to go into, given

that innumerable commentaries have been written on this topic in the last few

years. I will try to be brief. If we look back into the 1930s and 1940s, we see

clearly that two of the world's anti-democratic governments -- the imperialists

of Japan, and the brutal expansionist Nazis of Germany --

were replaced with democratic governments imposed by the intervention of the

allied forces in the post-war period.

The skeptics may argue that the rule of the game has changed now

and it does not work anymore. Afghanistan and Iraq are the most obvious examples

in their favor. They probably would appear correct.

Let us consider the intervention in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the mid-1990s. After

the downfall of communism, these regions ran into a disastrous civil war as a

result of religio-ethnic fighting between the minority Muslims and the majority

Christians. Unlike Afghanistan and Iraq, intervention quickly brought the

fighting and violence under control. Since then, reconciliation, reconstruction

and democratic processes have made steady progress. All indications suggest that

secular democracy and peace will continue to strengthen and be lasting. However,