Mormon History

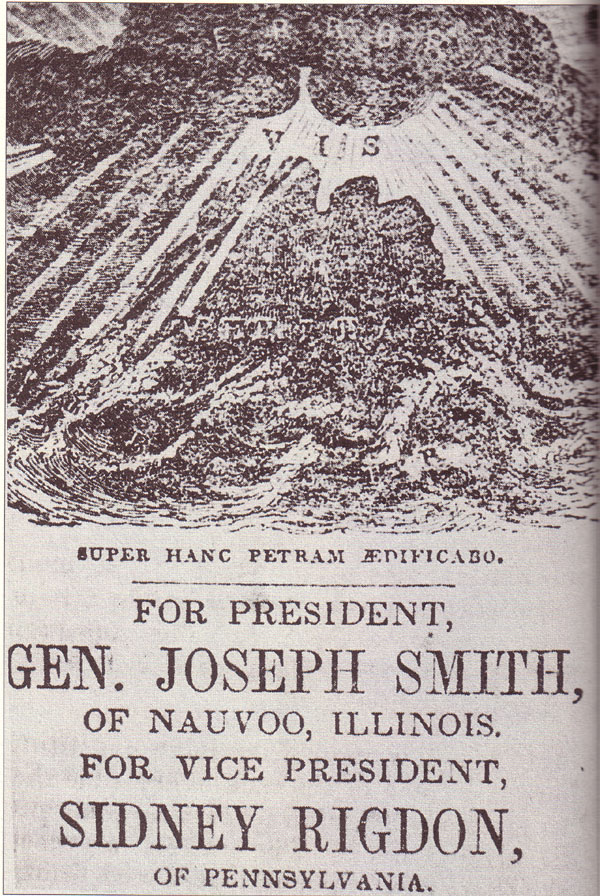

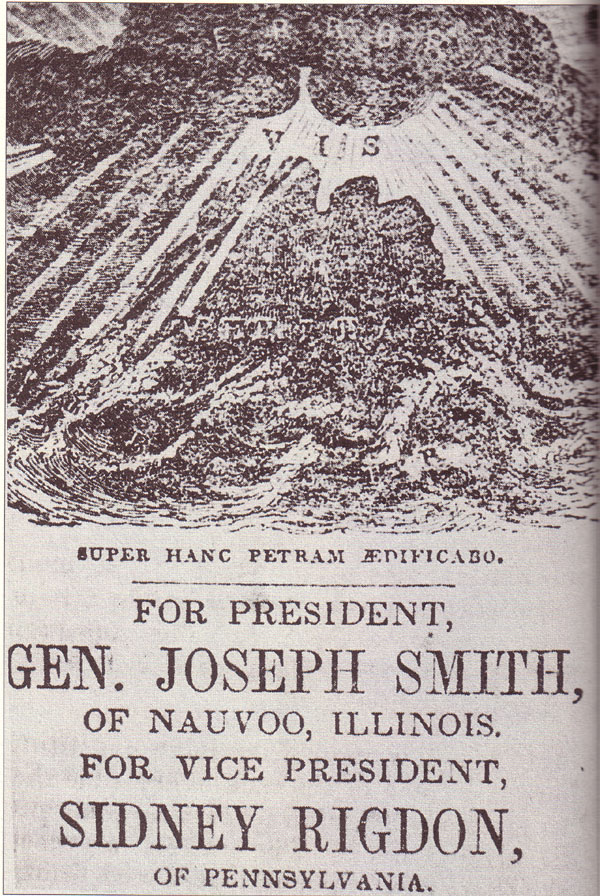

General Joseph Smith for President & Sidney Rigdon for Vice President - 1844

TIMES AND SEASONS

CITY OF NAUVOO

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 1844.

WHO SHALL BE OUR NEXT PRESIDENT?

This is an enquiry which to us as a people, is a matter of the most paramount importance, and requires our most serious, calm, and dispassionate reflection. Executive power when correctly wielded, is a great blessing to the people of this great commonwealth, and forms one of the firmest pillars of our confederation. It watches the interests of the whole community with fatherly care; it wisely balances the other legislative powers, when overheated by party spirit, or sectional feeling; it watches with jealous care our interests and commerce with foreign nations, and gives tone and efficacy to legislative enactments. The President stands at the head of these United States, and is the mouth-piece of this vast republic. If he be a man of enlightened mind, and capacious soul-if he is a virtuous man, a statesman, a patriot, and a man of unflinching integrity; if he possess the same spirit that fired the souls of our venerable sires, who founded this great commonwealth, and wishes to promote the universal good of the whole republic, he may indeed be made a blessing to community. But if he prostrates his high and honorable calling, to base and unworthy purposes; if he makes use of the power which the people have placed in his hands for their interests, to gratify his ambition, for the purpose of self-aggrandizement, or pecuniary interest; if he meanly panders with demagogues, looses sight of the interests of the nation, and sacrifices the union on the altar of sectional interests or party views, he renders himself unworthy of the dignified trust reposed in him, debases the nation in the eyes of the civilized world, and produces misery and confusion at home. 'When the wicked rule, the people mourn.'

There is perhaps no body of people in the United States who are at the present time more interested about the issue of the presidential contest, than are the Latter Day Saints. And our situation in regard to the two political parties, is a most novel one. It is a fact well understood, that we have suffered great injustice from the State of Missouri, that we have petitioned to the authorities of that state for redress in vain; that we have also memoralized congress, under the late administration, and have obtained the heartless reply that 'congress has no power to redress your grievances.' After having taken all the legal, and constitutional steps that we can, we are still groaning under accumulated wrongs. Is there no power anywhere to redress our grievances? Missouri lacks the disposition, and congress both lacks the disposition, and power and thus fifteen thousand inhabitants of these United States, can with impunity be dispossessed of their property, have their houses burned, their property confiscated, many of their numbers murdered, and the remainder driven from their homes, and left to wander as exiles in this boasted land of freedom and equal rights, and after appealing again and again, to the legally constituted authorities of our land for redress, we are cooly [coolly] told by our highest tribunals, 'we can do nothing for you? We have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into the coffers of congress for their lands, and they stand virtually pledged to defend us in our rights, but they have not done it. If a man steals a dollar from his neighbor, or steals a horse or a hog, he can obtain redress; but we have been robbed by wholesale, the most daring murders have been committed, and we are cooly told that we can obtain no redress. If a steam boat is set on fire, on our coast by foreigners, even when she is engaged in aiding and abetting the enemies of that power, it becomes a matter of national interference, and legislation; or if a foreigner, as in the case of McLeod, is taken on our land and tried for supposed crimes committed by him against our citizens, his nation interferes, and it becomes a matter of negotiation and legislation; but our authorities can calmly look on and see the citizens of a county butchered with impunity;-they can see two counties dispossessed of their inhabitants, their houses burned and their property confiscated, and when the cries of fifteen thousand men, women and children salute their ears, they deliberately tell us we can obtain no redress. Hear it therefore ye mobbers! proclaim it to all the scoundrels in the Union! let a standard be erected around which shall rally all the renegadoes of the land; assemble yourselves, and rob at pleasure; murder till you are satiated with blood, drive men women and children from their homes, there is no law to protect them, and congress has no power to redress their grievances, and the great father of the Union has not got an ear to listen to their complaints.

What shall we do under this state of things? In the event of either of the prominent candidates, Van Buren or Clay, obtaining the presidential chair, we should not be placed in any better situation. In speaking of Mr. Clay, his politics are diametrically opposed to ours; he inclines strongly to the old school of federalists, and as a matter of course, would not favor our cause, neither could we conscientiously vote for him. And we have yet stronger objections to Mr. Van Buren, on other grounds. He has sung the old song of congress-'congress has no power to redress your grievances.' But did the matter rest here it would not be so bad. He was in the presidential chair at the time of our former difficulties. We appealed to him on that occasion, but we appealed in vain, and his sentiments are yet unchanged. But all these things are tolerable in comparison to what we have to state. We have been informed from a respectable source, that there is an understanding between Mr. Benton of Missouri; and Mr. Van Buren, and a conditional compact entered into, that if Mr. Benton will use his influence to get Mr. Van Buren elected, that Van Buren when elected, shall use his executive influence to wipe away the stain from Missouri, by a further persecution of the Mormons, and wreaking out vengeance on their heads, either by extermination, or by some other summary process. We could scarcely credit the statement, and we hope yet for the sake of humanity, that the suggestion is false; but we have too good reason to believe that we are correctly informed.

If then this is the case can we conscientiously vote for a man of this description, and put the weapons in his hands to cut our throat with? we cannot; and however much we might wish to sustain the democratic nomination we cannot-we will not vote for Van Buren. Our interests, our property, our lives and the lives of our families are too dear to us to be sacrificed at the shrine of party-spirit, and to gratify party feelings. We have been sold once in the State of Missouri, and our liberties bartered away by political demagogues through executive intrigue, and we wish not to be betrayed again by Benton and Van Buren.

Under these circumstances the question again arises, who shall we support? General Joseph Smith. A man of sterling worth and integrity and of enlarged views; a man who has raised himself from the humblest walks in life to stand at the head of a large, intelligent, respectable, and increasing society, that has spread not only in this land, but in distant nations; a man whose talent and genius, are of an exalted nature, and whose experience has rendered him every way adequate to the onerous duty. Honorable, fearless, and energetic; he would administer justice with an impartial hand, and magnify and dignify the office of chief magistrate of this land; and we feel assured there is not a man in the United States more competent for the task.

One great reason that we have for pursuing our present course is, that at every election we have been made a political target for their filthy demagogues in the country to shoot their loathsome arrows at. And every story has been put into requisition to blast our fame, from the old fabrication of "walk on the water" down to "the murderer of ex-Governor Boggs." The journals have teemed with this filthy trash, and even men who ought to have more respect for themselves; men contending for the gubernatorial chair have made use of terms so degrading, so mean, so humiliating, that a billingsgate fisherwoman would have considered herself disgraced with. We refuse any longer to be thus debaubed for either party; we tell all such to let their filth flow in its own legitimate channel, for we are sick of the loathsome smell.

Gentlemen, we are not going either to "murder ex-Governor Boggs," nor a mormon in this state for not giving us his money;" nor are we going to "walk on the water;" nor "drown a woman;" nor "defraud the poor of their property;" nor send "destroying angels after Gen. Bennet to kill him;" nor "marry spiritual wives;" nor commit any other outrageous act this election to help any party with, you must get some other persons to perform these kind offices for you in the future.-We withdraw.

Under existing circumstances we have no other alternative, and if we can accomplish our object well, if not we shall have the satisfaction of knowing that we have acted conscientiously and have used our best judgment; and if we have to throw away our votes, we had better do so upon a worthy, rather than upon an unworthy individual, who might make use of the weapon we put in his hand to destroy us with.

Whatever may be the opinions of men in general, in regard to Mr. Smith, we know that he need only to be known, to be admired; and that it is the principle of honor, integrity, patriotism, and philanthropy, that has elevated him in the minds of his friends, and the same principles if seen and known would beget the esteem and confidence of all the patriotic and virtuous throughout the union.

Whatever therefore be the opinions of other men our course is marked out, and our motto from henceforth will be General Joseph Smith.

PUBLIC MEETING

On Friday evening last a public meeting was held in the room over Joseph Smith's store, at which public address, of General Joseph Smith's, to the citizens of the United States was read by Judge Phelps. The address is certainly an able document, big with meaning and interest, clearly pointing out the way for the temporal salvation of this union, shewing what would be our best policy, pointing out the rocks and quicksand where our political bark is in danger of being wrecked, and the way to escape it and evincing a knowledge and foresight of our political economy, worthy of the writer.

Appropriate remarks were made by several gentlemen after the reading of the address.

The Warsaw Signal – February 21, 1844

TO JO SMITH -- Prophet -- Candidate for the Presidency -- Mayor of the City of Nauvoo -- Lieutenant General of the Legion -- President of the Church -- Tavern Keeper -- Grog Bruiser -- &c., &c.

Sir: Understanding that you are a candidate for the highest office within the

gift of the People, we claim as the unalienable right of an American Citizen to

ask you a few questions, as regards the policy which you, as "His Excellency,

the President of the United States," will pursue.

Well Jo! if you should be so fortunate as to be elected President of the United

States, what would you do with the State of Missouri? Would you pluck out the

eyes of her soverignty? Or would you take her up in your expanded arms, and

giant-like stride across the Western Prairies -- leap the Rocky Mountains and

hurl her headlong into the angry Pacific, there to remain until purged of every

Anti-Mormon sin? Or Jo, would you Xerxes-like muster your myriads, and every man

armed with a hoop-pole, march across the icy bridge in winter time, and give her

Sovereign Highness, a most transcendent drubbing?

From the manner in which you write to J. C. Calhoun, we conclude that you had

some design of chastising Missouri, and we would like to know how you are going

to do it, and so no doubt would the people of that State.

Warsaw Messenger – April 24, 1844

CHURCH AND STATE. -- In the last Nauvoo Neighbor we find a long list of the names of Elders of the Churches in the different states of the Union; at the conclusion of which, they are instructed in these words, to "preach the truth in righteousness, and present before the people, "General Joseph Smith's views of the powers and policy of the General Government," and seek diligently to get up electors who will go for him for the Presidency," That's it Jo! "Preach the truth in righteousness, and go for Presidency. That is Mormonism disguised. First preach the gospel, and thereby gull the people, and then fleece them of their money, or induce them to elevate me to office." -- That is the sum and substance of all your teachings. Ain't it Joe.

The prophet and the presidency: Mormonism and politics in Joseph Smith's 1844 Presidential campaign

Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Summer 2000 by Wood, Timothy L

The kingdom of God is at the defiance of all earthly laws and yet breaks none.

- Joseph Smith, April 6, 1844 1

Resolved... that we ... discountenance every attempt to unite church and state; and that we further believe the effort now being made by Joseph Smith for political power and influence is not commendable in the sight of God.

Resolved... that while we disapprobate malicious persecutions and prosecutions, we hold that all church members are alike amenable to the laws of the land: and that we further discountenance any chicanery to screen them from the just demands of the same.

-Nauvoo Expositor, June 7, 1844 2

One of the most intriguing movements that sprang from the religious fervor of early nineteenth century America was the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, better known as the Mormons. Throughout its existence, the Mormon church has distinguished itself as one of the fastest growing religious denominations in the United States. That phenomenon was all the more surprising since in many ways the Mormon church represented a radical departure from both mainstream American culture and orthodox Christianity, while at the same time remaining a continuation and adjustment of that culture and faith.

However, at no point in its early history did the Mormon church so ambitiously attempt to influence the larger American society than in the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith's 1844 presidential campaign. Smith used his presidential platform to articulate a series of social ideals developed since the founding of the LDS church in 1830. As a religious leader, Smith harkened back to a day when the preponderance of society's moral and religious authority resided within local institutions, such as the church and an individual's immediate community. Smith believed that the primary duty of the federal government was to defend religious liberty and maintain an atmosphere in the United States where such communities grew and thrived. However, the shifts in doctrine that hit the LDS church during the early 1840s introduced several new practices, including polygamy that disrupted the social, political, and religious balance articulated in Smith's campaign. The Mormon prophet's dramatic change of course reenergized the church's enemies, leading him down a path that culminated in his own murder in June,1844.

Most contemporary scholarship on Mormonism may be seen as falling roughly within one of two schools of thought. The first was best expressed in Fawn M. Brodie's 1945 biography No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith the Mormon Prophet. Brodie's goal was first and foremost to understand Joseph Smith the man through the social and psychological forces that shaped his life. As Brodie herself put it: "The source of his power lay not in his doctrine but in his person, and the rare quality of his genius was due not to his reason but his imagination. He was a myth-maker of prodigious talent. And after a hundred years the myths he created are still an energizing force in the lives of a million followers. The moving power of Mormonism was a fable - one that few converts stopped to question, for its meaning seemed profound and its inspiration was contagious."3 As a historian, Brodie separated Smith's personal motives from his symbolic role within the larger Mormon movement. Ultimately, Brodie concluded that Smith was a brilliant con artist who came to believe in the delusion that he himself had engineered, all the while presiding over a growing community of faith motivated by values far different than his own.

The second approach to Mormon history is best represented by the LDS historians Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton in their 1979 book, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints. In the introduction to their work, Arrington and Bitton stated that: "Both authors of the present work are believing and practicing members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As such, we hope we have been able to discern some features of Mormon history ... that would elude the outside visitor.... At the same time ... we have sought to understand as scholars of any faith or no faith would seek to understand. But ... some matters can never by understood adequately except from within."4 Unlike Brodie, Arrington and Bitton recognized little discrepancy between the inner life and intentions of Smith and the church he founded. Where Brodie painted a portrait of duplicity, they saw unity of purpose. Consequently, Arrington and Bitton described early Mormonism as a coherent whole, with the movement's social, political, and religious ideas flowing seamlessly from Smith to the average Saint.

Indeed, one does not have to be a Mormon to take the movement seriously as a motivating force within the lives of many true believers. Within the culture of the early Latter-day Saints, the life and thought of Joseph Smith took on a life of its own, quite independent of the Mormon founder's original intentions. The faith of countless ordinary Mormon believers validated Smith's new religion as a cultural force. The noted anthropologist Clifford Geertz defined culture as "an historically transmitted pattern of meaning embodied in symbols."5 In the nascent Mormon culture of the mid-nineteenth century, Smith was such a symbol, and his teachings, whatever their origin, provided that matrix of meaning. Thus, it is entirely possible for scholars to examine the impact of Smith's life and thought within the context of the larger Mormon culture, without speculating one way or another on the inner religious experience of one individual.

In order to understand the Mormon culture from which Smith's 1844 campaign emerged, it is helpful to first have a general understanding of Mormon theology, as well as the history behind that doctrine. Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on December 23, 1805 in the small village of Sharon, Vermont, although he spent most of his adolescent years in rural Palmyra, New York. As a boy, young Joseph was very concerned about matters religious, and spent much time reflecting upon the differences and disputes between the rival evangelical sects then competing for converts on the frontiers of New York during the Second Great Awakening. Smith's first supernatural experience occurred when he was between fourteen and sixteen years of age. Years later, Smith recounted a vision in which God and Jesus Christ appeared to him in bodily form, forgave his sins, condemned all existing Christian denominations as corruptions of the true faith, and commanded the young seeker to maintain his spiritual purity by joining no church.6

Joseph's next and most significant revelation took place a few years later on September 21, 1823. In this instance, a celestial being known as Moroni appeared to Smith and revealed the existence of a set of golden plates buried in a nearby hill which contained the religious records of an ancient (but now extinct) North American civilization. With the help of a translating device identified as the Urim and Thummim, part of the priestly vestments briefly mentioned in such Old Testament passages as Exodus 28, Smith set about deciphering the tablets. By 1829 Smith completed the translation of the mysterious tablets and The Book of Mormon went to press.

Within the pages of The Book of Mormon, Smith recounted the epic struggle of the Hebrew prophet Lehi and his descendants for nearly one-thousand years. Warned in a vision to flee the impending destruction of Jerusalem, Lehi and his family escaped the city just before it was overrun by the Babylonian forces of King Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C. Led by God to seek out a new promised land, Lehi, along with his sons Laman and Nephi, constructed a ship and undertook a perilous voyage which would eventually lead them to North America (I Nephi). Over the course of time, Lehi's two sons become the patriarchs of two mighty, but diametrically opposed, civilizations in America. The Nephites were a godly people who practiced a pure religion corresponding almost exactly to that revealed to Joseph Smith two millennia later. Conversely, the Lamanites devoted themselves to evil, and posed themselves as the consistent adversaries of the Nephites. In fact, as recompense for their wickedness, God eventually cursed the Lamanites with dark skin, laying the groundwork for a persistent Mormon identification of dark-skinned peoples with sin (Alma 3:6).

The climax of The Book of Mormon is indicated by the appearance of Jesus Christ in North America during the three days between his death and resurrection in Jerusalem (III Nephi). Christ's appearance inaugurated a golden era of peace and brotherhood between the two warring civilizations which lasted several centuries. Eventually, apostasy set in and hostilities between the two peoples resumed (IV Nephi). The saga ends with a final battle between the Nephites and Lamanites at a place called Cumorah sometime during the fifth century A.D. In the end, after a fierce struggle, the Nephite culture was totally eradicated by the Lamanites (Mormon 8). The sole survivor of the onslaught was a Nephite prophet and historian named Moroni, who transcribed the history of his people and sealed it up, awaiting the day when God would allow the records to be rediscovered (Moroni 10).

The contents of The Book of Mormon seemed to offer compelling solutions to the spiritual dilemmas faced by religious seekers during the Second Great Awakening. Instead of the fractious denominationalism and theological quarreling of evangelical Protestantism, Smith offered a pristinely restored gospel which contained authoritative answers via direct divine revelations. The movement slowly began to win adherents, and by April 6, 1830 Smith had gathered enough followers to officially form what was then known simply as the "Church of Christ."

During the remaining fourteen years of Joseph Smith's life, the theological landscape of Mormonism underwent rapid expansion and development. By the time of Smith's murder the summer of 1844, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had emerged, not as merely another eccentric Protestant sect, but as what historian Jan Shipps has called a religion that distinguished its "tradition from the Christian tradition as surely as early Christianity was distinguished from its Hebraic context."7 On the most basic level, the God of Mormonism was believed to be the same deity worshipped in both the Jewish and Christian faiths. Indeed, the contemporary LDS theologian Bruce R. McConkie argued that Adam himself had practiced a proto-Mormonism during humanity's first generation, which was later lost through apostasy.8 Thus, Mormonism was always referred to as "the Restoration," due to the belief that many of the doctrines introduced by Joseph Smith had been known and practiced both in ancient Israel and during the apostolic period of the early church. However, the reintroduction of true gospel doctrine into those periods of apostasy required a belief in continued divine revelation. God must have the leeway to speak to humanity, correcting their errors and proclaiming lost principles anew. Thus, in contrast to the closed Biblical canon of most Christian churches, the Latter-day Saints have consistently argued that new revelations, with scriptural authority on the same level as the Bible, can be and have actually been, handed down to believers during this latest dispensation.

Because of that restorationist theology, Mormonism has rejected the religious creeds and confessions that have emerged throughout the course of post-apostolic Christianity as the products of a "Great Apostasy." Consequently, Smith had the opportunity to reconstruct the Mormon image of God from the ground up, unencumbered by the trinitarian formulations of such statements of faith as the Nicene Creed.9 Instead, the Saints began to conceive of a God who differed dramatically in nature from the triune deity worshipped in Christendom, and one who bridged the chasm between divinity and humanity in ways never before thought possible.

First of all, Smith construed the concept of monotheism far more loosely than was common within the Judeo-Christian tradition. Again, as McConkie put it, Mormon monotheism "properly interpreted ... mean[s] that the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost - each of whom is a separate and distinct godly personage - are one God, meaning one Godhead." However, McConkie is quick to stipulate, that "it is evident, from this standpoint alone, that a plurality of Gods exist."10

Indeed, one of the most valuable sources regarding the Mormon doctrine of the plurality of gods was the sermon Joseph Smith preached at the funeral of the LDS elder King Follett in April 1844. The fundamental principle which underlay that doctrine was Smith's belief in the eternal progression of humanity. Early in the sermon, Smith remarked that: "God himself was once as we are now, and is an exalted man, and sits enthroned in yonder heavens! That is the great secret. If the veil were rent today, and the great God who holds this world in its orbit, and who upholds all worlds and all things by this power, was to make himself visible, - I say, if you were to see him today, you would see him like a man in form - like yourselves in all the person, image, and very form of a man... ."11

Thus, the substance of divinity and the substance of humanity were essentially the same. The ways in which God surpassed humanity in wisdom and power derived from differences in degree, not of essence. In fact, "the mind or the intelligence which man possesses is co-equal [co-eternal] with God himself."12 Smith could then proclaim to his listeners that: "Here, then, is eternal life - to know the only wise and true God; and you have got to learn how to be gods yourselves, and to be kings and priests to God, the same as all gods have done before you, namely, by going from one small degree to another, and from a small capacity to a great one; from grace to grace, from exaltation to exaltation, until you attain to the resurrection of the dead, and are able to dwell in everlasting burnings, and to sit in glory, as do those who sit enthroned in everlasting power.13

Literally speaking, every human being who had ever walked the face of the earth might potentially be exalted to a level of divinity comparable to that of God. Consequently, any doctrine of original sin was incompatible with Mormon theology, since God and humanity were of the same essence. Thus, sin was only the result of humanity's poor decisions and lack of moral discipline in life rather than of any inherent flaw in human nature, since that nature was capable of eventual divinity. Thus, the Book of Mormon called infant baptism a "solemn mockery before God," because "repentance and baptism" ought only to be preached to "those who are accountable and capable of committing sin" (Moroni 8: 8-10). Infants, because they lacked a will developed enough to choose evil, need not be baptized for the remission of sins they had never committed. According to the Articles of Faith of the LDS church, "men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam's transgression."14

In a theological system with such a radically different perception of the human-God relationship, the doctrine of salvation was also bound to have dramatically different dynamics. According to McConkie, "one of the untrue doctrines found in ... Christendom is the concept that man can gain salvation... by grace alone and without obedience."15 Instead, along with faith, obedience to the restored gospel was considered an essential condition of redemption. Such obedience included acceptance of the Mormon faith through baptism, living a moral and godly life, and the completion of certain ceremonies and ordinances in the temple.

Indeed, the highest objective in the Mormon scheme of eternity was achieving after death the state of being known as the Celestial Kingdom. Into that kingdom, claimed Smith, entered all worthy Mormons; those who "received the testimony of Jesus, and believed on his name . . . that, by keeping the commandments, they might be washed and cleansed from all their sins, and receive the Holy Spirit. . . . (Doctrine and Covenants 91:5)"16 Within that Celestial Kingdom, the souls of redeemed Saints might continue their eternal progression to godhood. Within that realm, departed Mormons "are gods, even the sons of God" (D & C 91:5). To Smith, that level of exaltation was the ultimate end of humanity. Again, in the King Follett discourse, Smith declared: "The first principles of man are self-existent with God. God himself, finding he was in the midst of spirits and glory, because he was more intelligent, saw proper to institute laws whereby the rest could have a privilege to advance like himself. The relationship we have with God places us in a situation to advance in knowledge. He has power to institute laws to instruct weaker intelligences, that they may be exalted with Himself, so that they might have one glory upon another, and all that knowledge, power, glory, and intelligence which is requisite to save them in the world of spirits.""17 Thus, the revelations and commandments of Mormonism were the stepping stones to deity, and careful adherence to them was the key to transcending the secularism and sectarianism of early nineteenth century America.

Nevertheless, no matter how eagerly the Saints looked forward to their glorification in the next world, the business of everyday living must by necessity be carried out in this one. As the sociologist Thomas F. O'Dea has pointed out, the relationship between religious and secular authority during the early days of the Mormon movement was quite paradoxical. Although Mormonism came into being during a time of heightened democratic awareness in the United States, it quickly developed many authoritarian tendencies. According to O'Dea, as Mormonism developed a coherent church polity during the 1830s, a potentially unstable dichotomy emerged. On one side was the impulse toward congregationalism that so many of the New England Saints had been steeped in, which emphasized the authority and participation of the general membership. On the other hand, to avoid schism the church needed to contain religious charisma and innovation within the office of the prophet-president.18 To maintain any kind of unity of purpose, Smith alone had to be seen as the sole source of direction for the Restoration movement.

The resulting system has been characterized as "a willingly designated absolutism."19 Obviously, to allow the average member the same latitude allowed to Smith in delivering up prophetic revelations affecting the earthly destiny of God's true church would be to promote any number of withdrawals and secessions from the parent body as new "prophets" eagerly stepped forward into leadership positions. In order to cope with that tension, Smith oversaw the development of the Mormon church's extensive system of lay priesthood. Lacking a professional clergy, one of the signature traits of Mormonism has always been the induction of all male members of good standing into a multitiered priesthood. Thus, the work of "kingdom building" within the LDS church has always been widely distributed, offering opportunities for service to a large number of individuals.

However, at the same time Smith organized a hierarchy which

concentrated decision-making power within the church's upper echelons,

especially the First Presidency (the presidentprophet and his two

primary advisors) and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. As O'Dea

remarked: "Mormonism had attempted to reconcile prophetic leadership

with congregationalism, an attempt that worked itself out in the

context of common suffering and achievement. What had developed was a

democracy of participation and an oligarchy of decision making and

command. As hierarchical bodies evolved, they were filled with men

capable of exerting leadership. The development of a chain of command

meant also the promotion of potential leaders from below... Thus Mormon

authoritarianism drew its leaders from the ranks, and the ranks

supported such leaders."20 Ultimately, the role of the rank-and-file

membership became "a matter more of expression of assent" than the

exercise of any real power of leadership.21

However, the Saints' attitude toward power that originated from outside the church was markedly different. Indeed, a very favorable disposition toward the democratic form of government was detectable even within the pages of The Book of Mormon. That sentiment led the great Nephite ruler Mosiah to declare, "Now it is not common that the voice of the people desireth anything contrary to that which is right; but it is common for the lesser part of the people to desire that which is not right; therefore this shall ye observe and make it your law - to do your business by the voice of the people (Mosiah 29:26)." It seemed that inherently within the people, there existed a moral compass which was capable of steering rulers in the direction of just government. Good secular leadership was not authoritarian; rather, it concerned itself with meeting the people's needs and protecting their rights. Indeed, Mormonism also affirmed much of the natural rights theory which undergirded the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights. For instance: "We believe that no government can exist, in peace, except such laws are framed and held inviolate as will secure to each individual the free exercise of conscience, the right and control of property and the protection of life.

"We believe that religion is instituted of God, and that men are amenable to him and him only for the exercise of it, unless their religious opinion prompts them to infringe on the rights and liberties of others; but we do not believe that human law has a right to interfere in prescribing rules of worship to bind the consciences of men, nor dictate forms for public or private devotion; that the civil magistrate should restrain crime, but never control conscience; should punish guilt, but never suppress the freedom of the soul." (D & C 102: 2, 4) And again, in The Book of Mormon: "For there was a law that men should be judged according to their crimes. Nevertheless, there was no law against a man's belief; therefore, a man was punished only for the crimes which he had done; therefore all men were on equal grounds." (Alma 30: 11) Thus, protection of the free exercise of religion was one of the greatest expectations the Saints had of the United States government.

This principle suggests a paradox in the Mormon attitude concerning the relationship between religion and power. Within the church and the immediate community, Mormons tended to favor an authoritarian style of leadership, which enforced doctrinal conformity and defended such "peculiar" LDS social institutions as secret temple rituals and, eventually, polygamy. On the other hand, the constitutional theory articulated by Smith and his followers steadfastly advocated the principles of religious liberty and governmental noninterference with the religious lives of its citizens. Seen in that light, the Mormons demanded traits in their leaders at the state and national level that would have seemed quite distasteful to them if possessed by authority figures closer to home.

However, the LDS historian J. Keith Melville suggested that there existed a quite logical connection between the doctrines of Mormonism and the Saints' strong advocacy of the Constitution. As that scholar contended, "the principle of free agency - so vital doctrinally to all [Mormon] people in order that they might prove their worthiness and return to God as celestial beings - is fostered by the free environment provided by the Constitution.22 Thus, implicit in LDS theology was the necessity for the religion to exist within a free society. If one was ultimately to be saved by their works in this life, one must be allowed the opportunity to perform those works. Existing alongside the church's more authoritarian tendencies, then, was also the expectation that Mormonism could only flourish in a society that was free.

The tension between those two views of authority within the Mormon church became increasingly apparent in the years between the church's organization in 1830 and Smith's assassination in 1844. In 1831, Smith moved the church en masse from Palmyra, New York to Kirtland, Ohio. After a disastrous foray into the banking business, Smith and the Mormon church again migrated to Missouri in 1838, to join an existing LDS community which had been founded there in 1831.

The years spent in Missouri were one of the bitterest chapters in Mormon history. The old, non-Mormon population resented the intrusion of this strange sect into their territory, and violence soon erupted. Both sides denounced each other from the pulpit and in print, and both sides raised unofficial armies to terrorize one another. Finally, in 1839, Smith and his associates gave up the struggle with the intensely hostile Missourians, and retreated east to the small city of Commerce, Illinois, which the Saints renamed Nauvoo.23

In relocating to Nauvoo, Smith and the Mormons enjoyed a considerable number of privileges that they would never have thought possible during their Missouri years. The Illinois state legislature issued the Saints an exceptionally generous city charter, which allowed the Mormons a large degree of self-government. Illinois granted Nauvoo the authority to "make, ordain, establish and execute all such ordinances not repugnant to the Constitution of the United States or this State."24 The city held the power to muster its own militia, known as the Nauvoo Legion, which commissioned Smith as its commander, holding the rank of lieutenant general. (The Nauvoo Legion was one of the biggest causes for alarm among the areas non-Mormon population. One worried newspaper editor inquired, "What would be thought if the Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, or Episcopalians of this state had military organizations. . . ?")25 Under this charter the city flourished, until only Chicago rivaled it in population within the state of Illinois.26 Indeed, the Nauvoo charter was an instrument of government well suited to Smith's unique political philosophy. As historian Robert Bruce Flanders put it: "On its face it was just another city charter with some novel clauses; in operation it was a charter to create a Mormon kingdom in the sovereign state of Illinois. Smith conceived Nauvoo to be federated with Illinois somewhat as Illinois was federated with the United States, with strong legal and patriotic ties to be sure, but also with guaranteed immunities and rights of its own."27

Thus, having finally obtained a period of relative peace and prosperity after the intense persecutions of the previous decade, Smith set about the task of securing some sort of political protection for his oft beleaguered Saints. Smith looked to the upcoming presidential race, hoping to secure the ear of a candidate willing to come to the aid of the Mormons. As the Presidential election of 1844 approached, six potential candidates dominated the nation's political landscape. First was the Democrat and former president Martin Van Buren. Still stinging from his 1840 loss to William Henry Harrison, in 1844 Van Buren attempted a presidential comeback. Offering a platform which featured opposition to both the annexation of Texas and the expansion of slavery into the territories, Van Buren found that those positions would in fact cost him his party's nomination that year. John C. Calhoun was another prominent name who was considered for the Democratic nomination in 1844. An articulate spokesman for the slave culture of the South, Calhoun favored continued westward expansion, taking the "peculiar institution" in tow. However, his positive insistence on the virtue and morality of slavery greatly reduced his viability as a candidate for national office. Next was the last minute Democratic nominee and eventual victor, James Knox Polk. Polk was zealous in his desire to bring a slave-- holding Texas and a free Oregon into the Union, offering an expansionist option to voters which maintained the sectional balance between slave and free states.

Meanwhile, within the Whig camp, incumbent President John Tyler was denied renomination due to his party's dissatisfaction with his excessive use of the veto against their own legislation. Thus, the Whig nomination went to his inter-party rival Henry Clay, who ran on a platform advocating continued sectional balance between the slave and free states; however, he opposed risking war with Great Britain or Mexico in order to annex new territory. Finally, the staunchly abolitionist candidate of the dark-horse Liberty Party was James G. Birney. Running primarily on the slavery issue, Birney favored general emancipation and resettlement of the freed slaves in Africa or the Caribbean. Indeed, Birney's popularity in the Northern states drew key votes away from Clay, assisting Polk in his eventual victory.28

Joseph Smith watched the developing race with intense interest. Although Polk entered the race too late to be noticed by Smith, and the Mormon founder fundamentally disagreed with Birney's abolitionist stance, the Nauvoo mayor was especially interested in obtaining some kind of commitment or pledge of assistance from at least one of the other four remaining candidates. Each one received a letter from Smith requesting a redress of the Saints' grievances; each candidate avoided making Smith any promises. Smith did not attempt to hide his contempt over the noncommittal politicians of his day. No doubt Smith would have applied his written response to Henry Clay equally to Tyler, Van Buren, and Calhoun: "I mourn for the depravity of the world; I despise the imbecility of American statesmen; I detest the shrinkage of candidates for office, from pledges and responsibly; I long for a day of righteousness, when he 'whose right it is to reign, shall judge the poor, and reprove with equity for the meek of the earth,' and I pray God, who hath given our fathers a promise of a perfect government in the last days, to purify the hearts of the people and hasten the welcome day."29 Smith felt the time had come to make a bold statement. In order to demonstrate the political clout of the Mormons to the nation's two major parties, as well as to publicize his own views on the nature of government, Joseph Smith determined to offer himself as a candidate for the Presidency of the United States of America.

Upon announcing his candidacy, Smith composed a document entitled "Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States," his most comprehensive statement of political philosophy. Within that treatise, Smith outlined six major policies that he wished to implement if elected to the presidency: the gradual abolition of slavery, a reduction in the membership of Congress, the re-establishment of a national bank, a campaign for vast territorial expansion, a federal government empowered to protect the liberties guaranteed in the Constitution from acts of mob violence, and an agenda of radical prison reform.

The first of those policies was a plan for the gradual elimination of slavery. Indeed, only a few years earlier, in 1835, Smith had published a revelation in the Doctrines and Covenants that implies a very hands-off approach to the slavery issue. It read: ". . . but we do not believe it right to interfere with bond-servants, neither preach the gospel to, nor baptize them, contrary to the will and wish of their masters, not to meddle with, or influence them in the least to cause them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life, thereby jeopardizing the lives of men: such interference we believe to be unlawful and unjust, and dangerous to the peace of every government allowing human beings to be held in servitude." (D & C 102:12) However, by the time of the 1844 campaign, although still not an abolitionist, Smith embraced an anti-slavery platform. Towards the beginning of his "Views," Smith remarked that: "My cogitations ... have for a long time troubled me, when I viewed the condition of men throughout the world, and more especially in this boasted realm, where the Declaration of Independence 'holds these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;' but at the same time some two or three millions of people are held as slaves for life, because the spirit in them is covered with a darker skin than ours. . . ."30 However Smith was quick to renounce the abolitionist stance advocating the immediate termination of slavery. Reflecting Mormonism's long-standing suspicion of a professional, ordained clergy, Smith saw abolitionism as a form of sectional aggression engineered by the entrenched religious interests of the north. "A hireling psuedo-priesthood," argued Smith, "will plausibly push abolition doctrines and doings and 'human rights' into Congress, and into every other place where conquest smells of fame, or opposition swells to popularity."31

Instead, Smith wished to encourage a movement in which the slaveholding states would, by their own initiative, petition their individual legislatures to phase out slavery by 1850. In doing so, the southern states could put to rest any lingering northern doubts about the fundamental moral fabric of southern culture. Smith's administration would support that state-by-state movement by using federal funds obtained through the sale of western lands to reimburse slave owners for their lost property As he put it in his "Views": "The Southern people are hospitable and noble. They will help to rid so free a country of every vestige of slavery, whenever they are assured of an equivalent for their property.32 By liberating their slaves, not only would southerners be taking the moral high ground, but they would also undercut the dubious agenda of the abolitionists. In Smith's opinion, the moral imperialism practiced by such northern extremists as William Lloyd Garrison and the Beechers could only lead to "reproach and ruin, infamy and shame."33 Only with the South's cooperation could slavery be ended and national unity preserved.

Smith's next goal involved a vast reduction in the size of Congress. In his "Views," Smith announced his desire to: "Reduce Congress at least two-thirds. Two Senators from a State and two members to a million of population will do more business than the army that now occupy the halls of the national Legislature. Pay them two dollars and their board per them (except Sundays.) That is more than the farmer gets, and he lives honestly. . . ."34 Smith was distrustful of a federal government which seemed to be deliberately increasing its own power. Washington's proper sphere was oversight and regulation, and Smith sought to limit its size before it began to intrude upon the domain of local government and the community.

On the economic front, Smith argued intensely for the reestablishment of a National Bank. In order to appease those who felt that such an institution only served to increase the powers of the federal government at the expense of the states, Smith urged that a branch of the bank be located within each territory and state, with the bank's officers being elected by the people within its district. That bank would issue currency valid throughout the United States, and its profits would be rolled over into the coffers of the federal government (in the case of the central institution), or the states (in the case of the branches). In order to promote monetary stability and curtail inflation, Smith insisted on a dollar per dollar policy on the production of paper money; no bills could be printed without an equal amount of specie in the vaults to back them up.35

Smith also favored the annexation of Texas and Oregon to the United States. As the Mormon founder contended: "Oregon belongs to this government honorably; and when we have the red man's consent, let the Union spread from the east to the west sea; and if Texas petitions Congress to be adopted among the sons of liberty, give her the right hand of fellowship, and refuse not the same friendly grip to Canada and Mexico.36 Not surprisingly, Smith realized (as would Brigham Young a decade later) that the degree of liberty required to allow movements like his to flourish was greatly dependent upon the steady expansion of the frontier. The unsettled west invited social experimentation, while the ever-increasing population of the east and midwest meant criticism, conflict, and unrelenting pressure for conformity.

Smith also saw in the expanding frontier the potential for defusing sectional tensions concerning the growth of slavery. In a journal entry dated March 7,1844, Smith ruminated about the annexation of Texas and the corresponding concerns of Northerners that such an action would upset the nation's fragile sectional balance: "Don't let Texas go.. . . If these things are not so God never spoke by any prophet since the world began. I have been [discreet about what I know. In the struggle between the north and the] south, [if the south] held the balance of power by annexing Texas, [this could still be remedied]. I can do away [with] this evil [and] liberate [the slaves in] 2 or 3 states and if that was not sufficient, call in Canada [to be annexed]."37 Once again, in Smith's political thought the federal government assumed a regulatory role (in this case maintaining the balance between slave and free states), while moral issues were decided on a more local level. Indeed, Smith remained unwilling to force the South to emancipate their slaves. Rather, the Mormon founder hoped that through westward expansion, resolution of the problem of slavery might be postponed until the South, as a distinct regional community, could muster the moral strength necessary to eliminate the "peculiar institution" themselves.

No issue in Smith's platform was more inspired by the Saints' misfortunes that his insistence on the vigorous protection of constitutional liberties by the federal government. The Nauvoo mayor sought to defend Mormon political rights against the hostile local and state authorities who had so often encouraged violence against the Saints in order to crush the Mormon community. Smith believed that reason was of no use with such officials, whose lawlessness seemed to embody the old motto "talk not of law to men who wear swords."38 Smith pleaded that the electorate might see fit to "give every man his constitutional freedom and the president full power to send an army to suppress mobs, and the States authority to repeal and impugn that relic of folly which makes it necessary for the governor of a state to make the demand of the President for troops, in case of invasion or rebellion."39 Thus, Smith sought a central government strong and assertive enough to defend the rights of oppressed minorities against the "mobocracy" of unfriendly neighbors. Referring back to the Saints' bloody sojourn in Missouri, Smith even sought avenues for action in case "the governor himself may be a mobber," an explicit reference to Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs, who had used militia troops to drive the Mormons from his state in 1838. Smith intended to use the powers of the presidency to check the illegal power exercised by officials such as Boggs.

The final item on Smith's agenda, and perhaps the most radical plank in his platform, concerned a thoroughgoing reform of America's prison system. In his "Views," Smith exhorted America's citizens to: "petition your State Legislatures to pardon every convict in their several penitentiaries, blessing them as they go, and saying to them, in the name of the Lord, Go thy way, and sin no more."40

"Advise your legislators, when they make laws for ... any felony, to make the penalty applicable to work upon roads, public works, or any place where the culprit can be taught more wisdom and more virtue, and become more enlightened. Rigor and seclusion will never do as much to reform the propensities of men as reason and friendship. Murder only can claim confinement or death. Let the penitentiaries be turned into seminaries of learning, where intelligence, like the angels of heaven, would banish such fragments of barbarism.41 Again, on this issue Smith demonstrated his faith in the potential deification of humanity.42 A human race unfettered by the chains of original sin need not adopt a Draconian code of law. Smith also advocated the termination of imprisonment for debt, and of punishing soldiers for desertion. Smith believed that the thought of forfeiting honor would be incentive enough to keep military men at their posts.' Society's first response to crime ought to be an attempt to reintegrate the offender back into the community. Not unexpectedly, that proposal subjected Smith to a degree of ridicule. (An unfriendly newspaper editorial reprinted in the Nauvoo Neighbor remarked that "if this humane recommendation be adopted, the 'specie basis' would soon disappear from Joe's mother bank and branches . . . which would show a 'beggarly account of empty boxes.'")43 However, that view of prison reform was consistent with Smith's concept of the local community and its religious institutions as the level at which moral authority was ultimately exercised. Thus, the federal and state governments would assume a regulatory role in defining crime and overseeing the judicial process, but the reform of the individual perpetrator must be left to the community. By sentencing such convicts to meaningful labor within the community, Smith hoped that their morality might be improved, their personal honor restored, and that they might eventually be reassimilated into society as law-abiding and productive citizens.

Smith made the formal announcement of his candidacy on January 29, 1844. At first, James A. Bennett, a New York businessman, was selected as Smith's Vice Presidential candidate. However, after it was discovered that Bennett had been born in Ireland and was therefore ineligible for office, the number two position fell to Sidney Rigdon, Smith's close friend and advisor. As he launched his campaign, Smith admonished his supporters to "tell the people we have had Whig and Democrats Presidents long enough. We want a President of the United States."44 At the same meeting, Smith commissioned such prominent Mormon figures as Brigham Young, John Taylor, Parley Pratt, Sidney Rigdon, and Joseph's brother Hyrum to head to the east coast to electioneer for the Saints' candidate. During the following weeks of the campaign, Smith maintained an upbeat, yet realistic, attitude. Indeed, the Mormon founder openly admitted that the campaign was partially motivated by his desire to make the Saints' political clout felt on the state and national level. Smith stated that: "I do not care so much about the Pres[idential] election as I do the office I have got. We have as good a right to make political party to gain power to defend ourselves as for demagogues to make use of our religion to get power to destroy ourselves. We will whip the mob by getting up a President. Smith then quipped, "When I look into the eastern papers and see how popular I am, I am afraid I shall be President."45

Of course, Smith's bid for high office was greeted with enthusiasm within the Mormon community at Nauvoo. Inside the pages of the Nauvoo Neighbor, Smith was heartily endorsed on an almost weekly basis. The proclamation, or the Views of General Smith on the Powers and policy of the Government, is acknowledged by all parties to be the ablest document of the kind they ever saw... What a blessing to have a prophet and seer at the helm, to avert evils, and dispense bounteous blessings.... [Smith] fearlessly declares his political as well as religious principles .General Smith is the man that the God of heaven designs to make a savior of the nations now . . ."46

Travelers visiting Nauvoo wrote letters to the editor recording their favorable impressions of the Mormon prophet. From many reports, I had reason to believe [Smith] a bigoted religionist as ignorant of politics as the savage, but to my utter astonishment... I have found him as familiar with the cabinet of nations, as with his Bible. . . . Free from all bigotry and superstition, he dives into every subject, and it seems as though the world was not large enough to satisfy his capacious soul, and from his conversation, one might suppose him as well acquainted with other worlds as this."47 Mormon writers even compared Smith to such luminaries as America's first president. ". . . like a second Washington, he arms himself with the principles of Freedom, virtue, political economy, and religious rights, and with these weapons he combats the powers of political demagoguery until there shall be neither root nor branch left, to contaminate the free born sons of these United States."48

Occasionally, those accolades even came in verse:

Kinderhook, Kass, Kalhoun, nor Klay;

Kan never surely win the day.

But if you want to know who Kan,

You'll find in General Smith the man.49

Thus, despite Smith's awareness that his chances of victory were minuscule, he nevertheless took the time to develop a relatively rational and well-thought out platform, and invested a considerable amount of the church's resources (both human and financial) in advertising his campaign to non-Mormons who would not necessarily be sympathetic to his cause.

Indeed, despite the historiographical controversy concerning the genesis of Smith's ideas and his real intent in starting a church, by the time the Saints founded Nauvoo, the Mormon founder had developed a coherent and workable theory of government, authority, and power. Smith's politics were an odd conglomeration of seventeenth century religious communitarianism and eighteenth century natural rights philosophy, couched in the language of Jacksonian democracy. Like John Winthrop and many of the early Puritan settlers of America, Smith placed society's moral authority within the bounds of the community. Religion, ethics, and the development of group identity were all functions reserved for the church and the local government.

However, Smith recognized that America was a diverse society, and he highly valued the Constitution's guarantees of personal liberty. Indeed, the most important function of the federal government was to enforce those liberties. Ultimately though, Smith saw those liberties as applying primarily to individual communities more than they did to individual people. Therefore, people ought to have the right to join any community they so chose. Furthermore, it was incumbent upon the federal government to protect each community in the enjoyment of its Constitutional liberties. Smith saw the U.S. presidency as a guardian that must take upon itself the protection of the smallest and weakest of those communities from the often violent disapproval of its more powerful neighbors.

Thus, Smith could remark in the Nauvoo Neighbor of April 17, 1844 that "the world is governed too much, and there is not a nation or a dynasty now occupying the earth which acknowledges Almighty God as their lawgiver, and ... I go emphatically, virtuously, and humanely, for a Theodemocracy, where God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness."50 In Smith's eyes, this "theodemocracy" was the perfect democracy, where the government guaranteed all people the freedom to attach themselves to whatever moral community they desired. Thus, the people, through their elected government, wielded power which preserved liberty, while the community and its religious institutions undertook the development of public and private morality. A government, indeed, where God and the people seemed to rule together.

However, it would be the introduction of radical new doctrines into Mormonism during the Nauvoo period which would lead to the unraveling of Smith's "theodemocratic" principles, and, eventually, to the downfall of Mormonism in Illinois. The LDS church's open canon of scripture suggested the possibility that the next divine revelation might dramatically change the character of the faith. Such was the case with the doctrine of polygamy. As early as 1841 Smith had begun to teach the doctrine of plural marriage to the inner circle of Mormon leadership, and by 1843 he was recording his extra marriages in his journal.51 The introduction of polygamy into Mormonism had two major consequences. First of all, it introduced a large element of instability into Smith's political philosophy. If plural marriage were to be practiced within the LDS church, then suddenly the regulatory duties of the federal government were in direct conflict with the moral and spiritual mission of the community.

Secondly, the new body of doctrine alienated many Mormons who had

embraced the faith during the church's earlier days when it more

closely resembled traditional Christianity. The new revelations

concerning multiple marriage, along with the emerging doctrines

concerning the plurality of gods and eternal human progression,

precipitated a large departure from the church during the last year of

Smith's life. One of those people was a man named William Law. A former

counselor of Smith's, Law was appalled by the rumors of those novel

teachings, withdrew from the church and established an opposition press

known as the Nauvoo Expositor. In the Expositor's first and only issue,

the paper stated as its purpose the disclosure of the corrupt doctrines

that had taken hold within the Mormon church. Indeed, the Expositor was

not an anti-Mormon publication; the editors insisted on the first page

that "we all verily believe, and many of us know as a surety, that the

religion of the Latter Day Saints, as originally taught by Joseph Smith

... is verily true." However, the editors also exhorted the Saints to

not ". . . yield up tranquilly a superiority to that man which the

reasonableness of past events, and the laws of our country declare to

be pernicious and diabolical. We hope many items of doctrine, as now

taught, some of which, however, are taught secretly, and denied openly,

(which we know positively is the case,) and others publicly,

considerate men will treat with contempt; for we declare them heretical

and damnable in their influence, though they find many devotees."52

Concerning Smith's presidential ambitions, the Expositor remarked that: "We see that our friend the Neighbor, advocates the claims of Gen. Joseph Smith for the Presidency; we also see from the records of the grand Jury of Hancock Co. at their recent term, that the general is a candidate to represent the branch of the state government at Alton [prison]. We would respectfully suggest to the Neighbor, whether the two offices are not incompatible with each other.53

Of course, Smith and the church hierarchy at Nauvoo were outraged. Smith swiftly summoned the Nauvoo city council, and, declaring the Expositor a nuisance to be abated, had the press and as many issues of the paper as he could obtain burned. In a statement later published in the Neighbor, Smith accused the publishers of the Expositor of seeking "the destruction of the institutions of this city, both civil and religious." Consequently, "to rid the city of a paper so filthy and pestilential as this, become the duty of every good citizen, who loves good order and morality... If then our charter gives us the power to decide what shall be a nuisance and cause it to be removed, where is the offense? What law is violated? If then no law has been violated, why this ridiculous excitement and bandying with lawless ruffians to destroy the happiness of a people whose religious motto is 'peace and good will toward all men'?"54

Livid over the suppression of their paper, the anti-Smith party filed charges of inciting a riot against Smith at the county seat of Carthage, Illinois. Aware of the intense hostility that he aroused, Smith attempted to have the trial moved to Nauvoo, for fear of mob violence. Smith succeeded in obtaining a Nauvoo trial, but his acquittal there only heightened opposition and intensified demands that he face trial outside the city. Smith made plans to leave the city and flee west; however, when his absence was noticed, the posse sent to arrest him threatened to occupy Nauvoo. Messengers from the Mormon city caught up with Smith and convinced him to return for the sake of his people. On June 25, 1844, Smith was taken into custody and placed in the jail at Carthage, where he sat for two tense days. Finally, on June 27, an angry mob assembled outside the prison, stormed the building (with little resistance from the guards), and murdered Smith, shooting him as he leaped out a window for safety.55 Thus ended the personal political aspirations of the Mormon founder. However, the ideology he articulated would long survive him. Within three years of Smith's death, Brigham Young led the Saints' exodus from Nauvoo to the Great Basin, where Smith's social principles would be applied by the church on a far grander scale.

Joseph Smith devoted most of his adult life to the development of a religion that differed markedly from the forms of Christianity that had preceded it. As the Mormon church developed and articulated the concept of an actual physical gathering of believers, Smith's worldview expanded beyond the realm of mere speculative or revealed theology and grew to include social and political theory as well. Smith embraced an old-fashioned view of the church and community, believing those bodies to be the repository of society's moral and religious authority. However, Smith also embraced a limited concept of religious liberty, insofar as he believed the country's various communities ought to be able to coexist within one national entity, with individuals free to choose between them.

Thus, Smith's 1844 presidential campaign amounted to the Mormon founder's attempt to publicize those views on the national level. Smith advocated a platform which assigned the president a primarily regulatory role, vigorously defending religious freedom against the "mobocracy" and violence of hostile communities which might try to crush unpopular minorities simply by the power of their numbers. However, the introduction of new doctrines into the church, especially plural marriage, at a critical moment threw that political theory off balance, pitting the interests of the government in regulating marriage against the Saints' newfound belief in polygamy. Upset by that new course, former believers and supporters emerged as opponents, precipitating a series of crises that ended with Smith's murder in Carthage, Illinois in June 1844. However, the seeds of a new social order had been planted, seeds which would take root in Salt Lake City and produce a harvest that would greatly affect the future of American westward migration in the nineteenth century, and serve as the foundation of Utah's vital and dynamic religious culture in the twentieth.

Notes

1 Joseph Smith, An American Prophet's Record: The Diaries and Journals of Joseph Smith, ed. Scott H. Faulting (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1987), 464.

2 Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844, p. 2.

3 Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, Mormon Prophet. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), ix. Illinois Governor Thomas Ford, who presided over the state at the time of Smith's murder, expressed a similar sentiment when he reflected that: "The Christian world, which has hitherto regarded Mormonism with silent contempt, unhappily may yet have cause to fear its rapid increase. Modern society is full of material for such a religion. At the death of the prophet... the Mormons in all the world numbered about two hundred thousand souls...; a number equal, perhaps, to the number of Christians, when the Christian Church was of the same age. It is to be feared that, in course of a century, some gifted man like Paul, some splendid orator... may succeed in breathing new life into this modern Mahometanism, and make the name of the martyred Joseph ring as loud, and stir the souls of men as much, as the mighty name of Christ itself.... And in that event, the author of this history [Ford] feels degraded by the reflection, that the humble governor of an obscure state, who would otherwise be forgotten in a few years, stands a fair chance, like Pilate and Herod, by their official connection with the true religion, of being dragged down to posterity with an immortal name, hitched on to the memory of a miserable impostor." Thomas Ford, History of Illinois From its Commencement as a State in 1818 to 1847 (New York: S. C. Griggs and Company, 1854), 359-60.

4 Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1992), xv. For an explicitly Mormon interpretation of Smith's presidential campaign, see Richard Vetterli, Mormonism, Americanism and Politics (Salt Lake City: Ensign Publishing Company, 1961).

5 George M. Marsden, Religion and American Culture (Fort Worth, Texas: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1990), 4.

6 Arrington and Bitton, 5-8; Brodie 21-25, 405-10.

7 Jan Shipps, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1985), x. For a dissenting view that argues for the continuity of Mormonism within traditional American Christianity, see Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1993). Those same issues are also taken up in Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

8 Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1979), 16-18, 333.

9 The Nicene Creed states "We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the onlybegotten of the Father, that is, from the substance of the Father, God of God, light of light, true God of true God, begotten, not made, of one substance with the Father, through whom all things were made, both in heaven and on earth, who for us humans and for our salvation descended and became incarnate, becoming human, suffered and rose again on the third day, ascended to the heavens, and will come to judge the living and the dead. And in the Holy Spirit." Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1984), 1:165.

11 Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: History of Joseph Smith, the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1980), 6:305.

12 Ibid., 6:310. Brackets inserted by editor.

16 All quotations from The Doctrine and Covenants are taken from the first edition, published in Kirtland, Ohio in 1835. Subsequent editions rearranged the system of numbering the various sections and articles.

18 Thomas F. O'Dea, The Mormons (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1957), 160-65.

22 J. Keith Melville, "Joseph Smith, the Constitution, and Individual Liberties," BYU Studies 28 (Spring 1988): 65-74.

23 Arrington and Bitton, 61-64. For a comprehensive history of early Illinois, see James E. Davis, Frontier Illinois (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1999).

24 Brodie, 267. Thomas Ford later remarked that this clause seemed to give the city the "power to pass ordinances in violation of the laws of the State, and to erect a system of government for themselves." Ford, 264.

25 Robert Bruce Flanders, Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1975), 113.

26 Arrington and Bitton, 68-69; Brodie, 256-74. In 1844, Thomas Ford estimated Nauvoo's population to be between 12,000 - 15,000 residents. Ford, 320.

28 For further information on the issues that loomed large on the American political scene in the two decades before the Civil War, see David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861 (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1976).

37 Smith, Diaries and Journals, 457. Brackets inserted by editor.

38 Nauvoo Neighbor, 3 April 1844, p. 1.

43 Neighbor, 10 April 1844, p. 2.

44 Smith, Diaries and Journals, 443.

46 Neighbor, 3 April 1844, p. 1.

47 Neighbor, 10 April 1844, p. 3.

48 Neighbor, 1 May 1844, p. 2.

49 Neighbor, 27 March 1844, p. 2.

51 Arrington and Bitton, 69; Smith, 387.

52 Expositor, 7 June 1844, p. 1.

54 Neighbor, 19 June 1844, p. 3.

55 In retrospect, Thomas Ford saw the eruption of violence against the Mormons as a failure of frontier democracy. Ford contended that: "If the people will have anarchy, there is no power short of despotism capable of forcing them to submission; and the despotism which naturally grows out of anarchy, can never be established by those who are elected to administer regular government. If the mob spirit is to continue, it must necessarily lead to despotism; but this despotism will be erected upon the ruins of government, and not spring out of it .... Where the people are unfit for liberty; where they will not be free without violence, license and injustice to others; where they do not deserve to be free, nature itself will give them a master. No form of constitution can make them free and keep them so. On the contrary, a people who are fit for and deserve liberty, cannot be enslaved." Ford, 435-36.

However, over half a century later, historian Theodore Calvin Pease still offered a classic rationalization of anti-Mormon violence as a "safety valve" against the encroachment of theocracy when he remarked: "After full allowance is made for the violence and perhaps greed of the opponents of the Mormons in Illinois, it must be admitted that they saw clearly how terrible an excrescence on the political life of the state the Mormon community would be, once it had attained full growth. Because legal means would not protect them from the danger they used violence. The machinery of state government was then ... but a slight affair; and to enforce the will of public opinion, the resort to private war, though to be deplored, was inevitable." Theodore Calvin Pease, Centennial History of Illinois, It: The Frontier State, 1818-1846 (Springfield: Illinois Centennial Commission, 1918), 362.

Timothy L. Wood holds an M.A. in history from the University of Louisville and is currently a Ph.D. candidate at Marquette University in Milwaukee. He has previously written on such topics as the impact of Puritanism and Methodism on early America, and his work has appeared in such journals as The New England Quarterly, Fides et Historia, Methodist History, and Rhode Island History. He presently resides in his hometown of Clarksville, Indiana.

Polygamy exposure sank Joseph Smith's run for White House

The Salt Lake Tribune

08/24/2008

Joseph Smith

petitioned the candidates for U.S. president in 1844 seeking redress on

behalf of his Mormon followers. The Mormons deserved federal protection

from mobs and persecution, he argued. Not one gave him the time of day.

Smith's frustration with politicians running for office has echoed

through the ages. "I despise the imbecility of American statesmen; I

detest the shrinkage of candidates for office."

Looking around for someone not an imbecile nor in danger of

shrinkage, Smith noticed himself. If no one would take up the Mormons'

political cause, then he would. In late January he declared his

candidacy for president.

The campaign, however, immediately stumbled. It was discovered that

his first pick as a running mate, James Bennett, a New York

businessman, had been born in Ireland and was, therefore,

constitutionally unqualified.

But his second pick, Sidney Rigdon, a longtime friend and

counselor, was American-born.

Smith set about developing a platform and a campaign organization.

He produced a raft of what we call today "policy papers." Besides

seeking protection for Mormons, he also touched on slavery, a proposal

to reduce the size of Congress by two-thirds and radical prison reform.

Despite saying nasty things about Northern abolitionists, Smith was

troubled when he saw, "the condition of men . . . in this boasted

realm, where the Declaration of Independence 'holds these truths to be

self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by

their creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are

life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;' but at the same time some

2 or 3 millions people are held as slaves for life because the spirit

in them is covered with a darker skin than ours. . . ."

Smith recommended the emancipation of all slaves by 1850 through a

program of monetary restitution to the owners.

But it was Smith's views on incarceration (of which he had some

experience) that would land him squarely in the liberal-nutcake wing of

the political landscape.

"Petition your state legislatures to pardon every convict in their

several penitentiaries, blessing them as they go, and saying to them,

in the name of the Lord, go thy way, and sin no more.

Smith saw "reason and friendship" as more effective in reforming

offenders than tossing them in the pokey.

Smith also floated something he called "Theodemocracy." In theory

it was to be the best of republican democracy married to enlightened

religiosity. Brigham Young later carried the concept with him when he

settled the church in the Great Basin. In practice, the U.S. government